This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

An index of the complete series (updated as each

article is posted) can be found here.

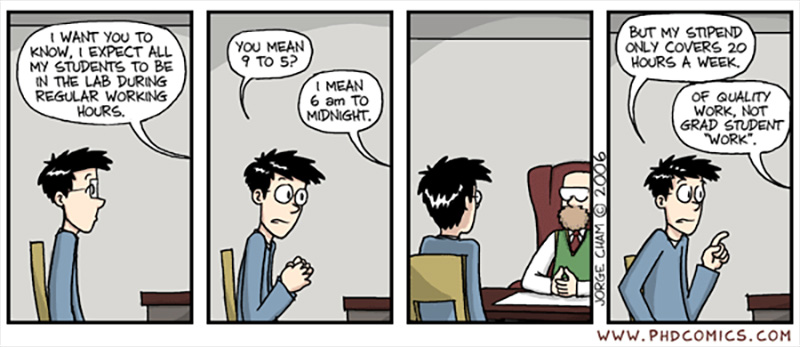

The second to the last item on the draft document is the only one that concerns our work with students — odd, if you think about it, since much of teaching concerns preparing them to be researchers themselves, so you’d think that a statement on research responsibilities would give some attention to our role mentoring the next generation of scholars. But, instead, the only attention to students reads as follows:

If there’s been little to no explicit awareness of the loaded nature of terminology so far in the document, then there’s surely no reason to expect it to start now, given that we’ve reached its penultimate section. So we have little choice but to accept that the slippery term “collegiality” is used here as if it is self-evidently meaningful, making it yet another example of how the document fails to live up to the standards that (I would hope) many of us work to attain in our own research (e.g., clearly define your terms, recognize which are contested, identify your assumptions and mount a persuasive case for why you use the term as you do, etc.).

If there’s been little to no explicit awareness of the loaded nature of terminology so far in the document, then there’s surely no reason to expect it to start now, given that we’ve reached its penultimate section. So we have little choice but to accept that the slippery term “collegiality” is used here as if it is self-evidently meaningful, making it yet another example of how the document fails to live up to the standards that (I would hope) many of us work to attain in our own research (e.g., clearly define your terms, recognize which are contested, identify your assumptions and mount a persuasive case for why you use the term as you do, etc.).

Now, this recurring shortcoming tells me that the document is merely boilerplate — or, if meant to be substantive, then, in an unintended fashion, it tells us much about an unarticulated consensus (some would term it a hegemony, perhaps) that exists within the field (as represented by the committee) concerning the assumed norms of the profession. It’s for this reason that, in many ways, reading this document carefully has amounted to a fieldwork experience.

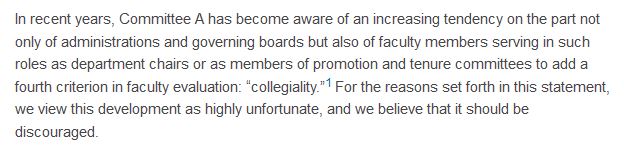

But, returning to that notion of collegiality, what’s curious is that amidst the committee’s various links to other documents (cited in their footnotes), there’s nothing linking to the American Association of University Professors’ 1999 report on “Collegiality as a Criterion in Faculty Evaluation.” For there, near the opening, we read the following:

The document argues that collaboration and cooperation — if this is what we mean by collegiality — already inform our activities in the three traditionally-assessed areas of teaching, research, and service (meaning that its already being assessed), so singling out collegiality, as some schools and departments do, for specific attention outside of these three areas, suggests that the term is being used in a new way.

As phrased by the AAUP document:

Historically, “collegiality” has not infrequently been associated with ensuring homogeneity, and hence with practices that exclude persons on the basis of their difference from a perceived norm. The invocation of “collegiality” may also threaten academic freedom. In the heat of important decisions regarding promotion or tenure, as well as other matters involving such traditional areas of faculty responsibility as curriculum or academic hiring, collegiality may be confused with the expectation that a faculty member display “enthusiasm” or “dedication,” evince “a constructive attitude” that will “foster harmony,” or display an excessive deference to administrative or faculty decisions where these may require reasoned discussion. Such expectations are flatly contrary to elementary principles of academic freedom, which protect a faculty member’s right to dissent from the judgments of colleagues and administrators.

A distinct criterion of collegiality also holds the potential of chilling faculty debate and discussion. Criticism and opposition do not necessarily conflict with collegiality. Gadflies, critics of institutional practices or collegial norms, even the occasional malcontent, have all been known to play an invaluable and constructive role in the life of academic departments and institutions. They have sometimes proved collegial in the deepest and truest sense. Certainly a college or university replete with genial Babbitts is not the place to which society is likely to look for leadership.

Given how unstable this signifier, collegiality,” can be, and how its unspecified use can signal possible mischief — especially when used in situations where power relations are askew (such as assessing job applicants, tenure-track faculty members for career advancement or, in the case of the draft document, making claims about our behavior toward students) — I’d invite the committee to rethink what it intends to say in this item. After all, apart from recommending being collegial and providing clear expectations, all the committee does in this bullet point is provide a list (not unlike their earlier remarks on human subjects research) of laws (not just “guidelines”) that already apply to our workplaces.

Given how unstable this signifier, collegiality,” can be, and how its unspecified use can signal possible mischief — especially when used in situations where power relations are askew (such as assessing job applicants, tenure-track faculty members for career advancement or, in the case of the draft document, making claims about our behavior toward students) — I’d invite the committee to rethink what it intends to say in this item. After all, apart from recommending being collegial and providing clear expectations, all the committee does in this bullet point is provide a list (not unlike their earlier remarks on human subjects research) of laws (not just “guidelines”) that already apply to our workplaces.

So I’m not sure how much we’ve gained by having our main professional association recommend, by means of this document, that, when it comes to research assistants, we pay attention to issues of pay equity, workplace safety, and harassment.

And so, once again, that’s why this document, despite ambitions to amount to a series of practical guidelines, reads to me as uncreative boilerplate that, at some future point, might provide legal cover for the Academy should someone accuse it of never telling its members not to harass people who work with or for them or to tell the truth. While recognizing the practical conditions in which we work, in this rather litigious society, I’d challenge the committee to do better than that; and we can start in this one item that happens to mention students.

As a suggestion, why not consider advocating for us to regularly co-author articles with our grad students — the job market is now so bad that seeing the AAR take a strong stand on what it means to mentor the next generation of academics would be helpful. Speaking here as someone who has now been a Department chair for a decade, and who has been involved in many search committees over the years, I’m still amazed by the CVs that come in from some early career people who seem to have never been told that they likely need to be writing and publishing despite also working on their dissertations (at least writing book notes, book reviews, abstracts, anything). While the sort of continually escalating credential inflation that comes with the buyer’s market that we’ve long seen developing in the Humanities is lamentable, it is among the facts that we now live with; so, does graduating doctoral students who have no publications whatsoever (in some cases few if any conference presentations, regardless whether at the national level or not) amount to responsible mentoring of researchers?

While any talk of students might sound to the committee like we’re inappropriately turning their document into a statement on teaching, I think that’s a far too compartmentalized view of what we do as scholars. Undergraduate research is a catchphrase that’s caught on significantly over the past few years in North American higher ed (no less than digital humanities, I’d argue), but the committee might not be thinking too much about undergrads in their document. If so, then I’d encourage them to reconsider that. For this item is a chance to make a bold statement about the minimal conditions that they think ought to exist in our efforts to replenish the institution in which we work with innovative and rigorous researchers who will follow us.

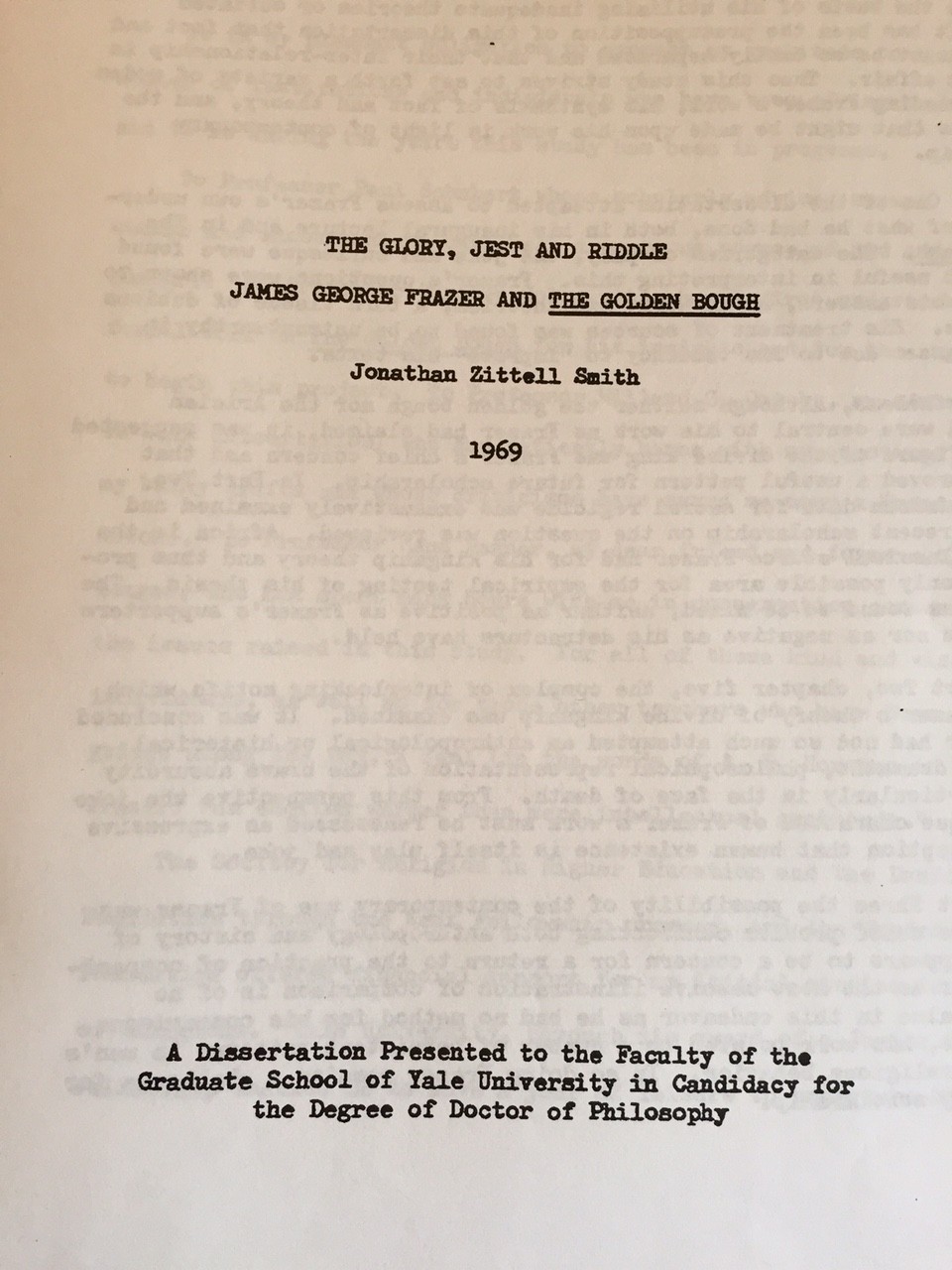

So…, should we be co-authoring with our students? Should we be writing them into grants? (Curiously, encouragement to apply for grants to support research, or maybe even to support our students, is mentioned nowhere in the document.) Should we be looking for opportunities to collaborate with other universities in our region, creating informal (or even formal) research networks in order to capitalize on resources (given ever-shrinking budgets, at least in many state schools)? What responsibilities does a supervisor or member of a supervisory committee have toward a doctoral student — especially when, given our current job market, that dissertation will likely have to be innovative enough to get published so as to give the student as much of a leg up as possible once they graduate and start looking for full-time work. (There was a day, of course, when dissertations were rarely published…

But those days are long gone — in fact, they had already passed when I defended my dissertation 20 years ago.)

But those days are long gone — in fact, they had already passed when I defended my dissertation 20 years ago.)

In fact, I know few, if any, scholars of religion who carry out their own research without interacting with students; and I don’t just mean employing them, as in this bullet point. Instead, I have in mind how we try out ideas in our classes, how something a student says or writes in a paper prompts us to see something in a new light, if only because it’s evident they didn’t “get” our point and so we’re challenged to retreat and rephrase it. And how our students are a barometer of what’s happening out there in the so-called real world — our research is often shaped, in its earliest stages, by what we realize our students didn’t know or, in our opinion, need to hear (and if them, then perhaps others too). And how all of this percolates into our scholarship, which then feeds back into the research results (i.e., books, articles, etc.) that we then assign in classes that have been produced by yet others, who were likely also teachers, working out novel ideas in novel ways while standing in front of a group of undergrads or while working through a graduate seminar.

And around and around it goes…

Of course this hardly exhausts the topic; all I’ve aimed to do is to suggest that the committee rethink the place of students in what it is that we call research, for if they do then I’d predict that they would propose that we, as researchers, have a much richer series of obligations to fulfill with regard to the students with whom we work.

For at least in my case, my research is intimately linked to what I teach, and vice versa.