This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

An index of the complete series (updated as each

article is posted) can be found here.

The previous post ended by citing the fourth of Bruce Lincoln’s “Theses on Method” — specifically, his call for scholars always to contextual, historicize, what they study by asking “who speaks here?” and “to what audience?” Among my difficulties with the AAR’s draft document is that it reads as if its authors had never read or taken seriously comments on the field such as Lincoln’s. Again, while I have no idea what debates took place between the members — or better yet, what compromises were required — reading their draft’s second bullet point’s advice that we “promote good” by, among other things, “telling the truth” flies in the face of Lincoln’s own widely read thoughts on what we ought to be doing in this field when we do research.

For instance, in light of their recommendation that we tell the truth, his concluding lines to this one thesis statement are particularly relevant:

When one … fails to distinguish between “truths”, “truth-claims”, and “regimes of truth”, one has ceased to function as historian or scholar. In that moment, a variety of roles are available: some perfectly respectable (amanuensis, collector, friend and advocate), and some less appealing (cheerleader, voyeur, retailer of import goods). None, however, should be confused with scholarship.

Now, any undergraduate student who submitted a paper to me and simply talked about “telling the truth” in it, as if it was a clear cut idea of self-evident meaning, would be greeted by a reference to the above quoted lines and an invitation to consider what Lincoln might have meant by distinguishing between those three different ways of talking about truth — correction, one way of talking about truth, one way of talking about people who talk about truth, and a final way to talk about the contingent conditions in which claims gets to be judged true and people truthful. A strong grade in my classes is linked to a student’s ability to unpack — as Lincoln does here — the claims people make (including their own, since we’re people too).

So among the things that’s so discouraging about the draft document is that it exemplifies little self-reflection and typifies how theoretical and critical work is often treated in the field — it’s read, maybe it’s even quoted and cited, but then without even offering a rebuttal it’s often business as usual, as if the critical comments had never been uttered.

Which reminds me of a recent conversation with a colleague, Mike Altman, who is part of a group here at Alabama writing review essays on the new Norton Anthology of World Religions, and who found a citation to Tomoko Masuzawa’s work on the invention of the world religions discourse in the volume’s introduction — you’d think that one would see her work as tremendously at odds with such an anthology (let alone world religions textbooks, classes, etc.) and thus requiring some detailed response before such a project proceeds. But no, that’s not the case here, for her critique is read as not being about the discourse on world religions (like “regimes of truth,” the institutional and intellectual conditions that allow us to think that particular identity and grouping into existence and into agency) but, instead, as just concerned with the term itself (i.e., in a typically conservative fashion, the words are somehow thought to float free of the phenomenon being named); so the introduction goes on, as if her critique had never been made, since we all just know that the world religions have been around for eons even if no one called them that until recently, right? For entertaining the alternative — that knowing they’ve been around for eons is itself an anachronistic move that shows that very discourse to be up and running — is something we prefer not to have to consider, I guess.

Although I know that redefining critiques out of existence, which pretty much amounts to ignoring the critique altogether, is among the best ways of dealing with them, I would have expected more from this draft document. But we end up with a document that informs us to be honest and good and tell the truth. However, as I also posted last time, I’m not sure what effect the document will even have — i.e., I don’t see it being linked to an AAR tribunal that would enforce it and, possibly, censure those who fail to follow its guidelines, so there seems to be little at stake in such a document. Accordingly, repeating apparent truisms with no elaboration or complication (“tell the truth…”) might be all that is required.

Which brings me to the third bullet point:

Now, filing an IRB (Institutional Review Board) proposal for doing research on human subjects is a requirement of my employer, as it probably is of yours (at least here in the US), because it is mandated by federal law.

Now, filing an IRB (Institutional Review Board) proposal for doing research on human subjects is a requirement of my employer, as it probably is of yours (at least here in the US), because it is mandated by federal law.

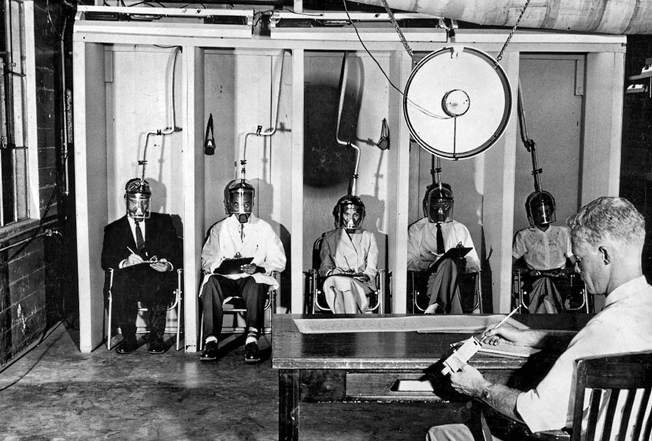

So what we have in bullet point three is the bold recommendation that members follow the law. There’s related law in Canada, of course, and the World Health Organization has its own principles, as well as pretty much every country in which AAR members likely do their work — which is not surprising given that the development of these sorts of regulations (i.e., they’re not just guidelines) in the mid-20th century followed on the heels of what many of us, worldwide, today would see as some pretty gruesome studies on imprisoned, live human subjects carried out in, among other places, Nazi Germany during World War 2. (To be fair, as readers may know, the US has had some pretty troubling experiments as well.) Which, after the war, led to trials of German doctors… Which led to 1947’s Nuremberg Code — the first such normative statement on ethical ways of working with research subjects.

So what we have in bullet point three is the bold recommendation that members follow the law. There’s related law in Canada, of course, and the World Health Organization has its own principles, as well as pretty much every country in which AAR members likely do their work — which is not surprising given that the development of these sorts of regulations (i.e., they’re not just guidelines) in the mid-20th century followed on the heels of what many of us, worldwide, today would see as some pretty gruesome studies on imprisoned, live human subjects carried out in, among other places, Nazi Germany during World War 2. (To be fair, as readers may know, the US has had some pretty troubling experiments as well.) Which, after the war, led to trials of German doctors… Which led to 1947’s Nuremberg Code — the first such normative statement on ethical ways of working with research subjects.

My point?

While silent on detailed elaborations of the technical, moral terms that they use in their document and, in my opinion, while side-stepping major debates taking place in the current field (debates which the graduate students with whom I interact on social media are more than aware — e.g., Lincoln’s theses, whether agreed with or not, are routinely cited in our exchanges, making them a reference point for people game to think seriously about what it is we do as scholars), the committee decided to take a strong stand on having members follow the law.

(Aside: since this is the only bullet point that advocates following the law, should we interpret this to mean the committee takes a strong stand on law and order or, perhaps, might it consider situations in which following the law might present researchers with restrictions that improperly limit their ability to carry out their work? When discussing this with another colleague, Merinda Simmons, she raised the case of countries where governments tightly control how one talks about the things that scholars of religion study [case in point, Saudi Arabia] — what might a researcher’s responsibilities be in such cases? Could the committee’s document help us to think this through?)

But like I said, I find truisms in this document and, sadly, little substance that presses our field forward; as I’ve written before, if these guidelines are to be used in people’s careers then the committee should produce a document that helps people to grapple with the ambiguity of real life situations and not simply recommend that we file an IRB — we learned that in grad school (if, that is, our supervisors were living up to their responsibilities while training us; that the document is silent on the obligations of how we train the next generation of researchers is troubling as well — but more on that in a later post).

And so to return to Lincoln’s above-quoted thesis, what’s curious is how a document that aims to inform us of what our responsibilities are, as researchers, itself fails to live up to the standards for scholarship that at least he identifies (i.e., “When one … fails to distinguish between ‘truths,’ ‘truth-claims,’ and ‘regimes of truth,’ one has ceased to function as historian or scholar….”). Should you agree with Lincoln, then what grade would you give this draft document?