Several weeks ago, along with Prof. Ramey, Caity Bell, Savanah Finver, and Keely McMurray (all first-year MA students in the study of religion) took the two hour drive to Montgomery, AL, to explore a variety of historical representations in museums and memorials. They began their tour at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice before visiting the Legacy Museum and finishing at the Alabama State Archives Museum.

Prof. Ramey, who teaches the required REL 501 Social Theory Foundations each Fall semester, planned the trip to give students an opportunity to apply some social theory in a real-life setting. Much like a novelist, Ramey notes, historians, museum curators, and almost all social groups make decisions on how to present information about the past.

Located just outside the Legacy Museum, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates all the documented cases of lynching across the United States. Opened in April 2018, the memorial has been widely featured in a variety of media, inasmuch as it is among the few places in the US that explicitly acknowledges and marks these infamous crimes.

The memorial consists of several sculptures (depicting events like the Montgomery Bus Boycott and slavery), a reflection space in honor of Ida B. Wells, writings from authors like Toni Morrison, and, most notably, 800 metal blocks heavily hanging from the roof. Each rectangle is engraved with the names of documented lynching victims and the county where the crime was committed.

Prof. Ramey recalls walking through the memorial, which begins at ground level and slowly lowers below ground, forcing viewers to crane their necks to get a glimpse of every county represented. He noticed his natural inclination to look for places he was familiar with and that the blocks lack of organization required visitors to walk the entire memorial. In fact, visitors might notice the eventual discomfort in their necks from being forced to look upwards as they move through the memorial reading the names — something our students concluded as being part of the experience intended by the museum’s designers. For the hanging structures mirror the victims they represent and a visitor’s descent deeper into the earth, moving through the exhibit, eerily parallels a trip to the grave. The architectural design of the monument therefore promoted a sense of physical immersion that was difficult to ignore.

While the Legacy and Archive Museums were less dramatic and architecturally stimulating, the contrast in their presentation of material gave the MA students another opportunity to apply social theory outside of the classroom. One exhibit (that stood out for Prof. Ramey) claimed there were more slave markets in Montgomery than churches. This classification, though, was more significant than it might have seemed at first glance, since it included such places as banks and law firms that handled the many slave transactions, among other legal negotiations, and not just areas used explicitly to auction slaves. This far larger definition of slavery and the institutions required to support it (and benefit from it) created a deeper impact on the viewer.

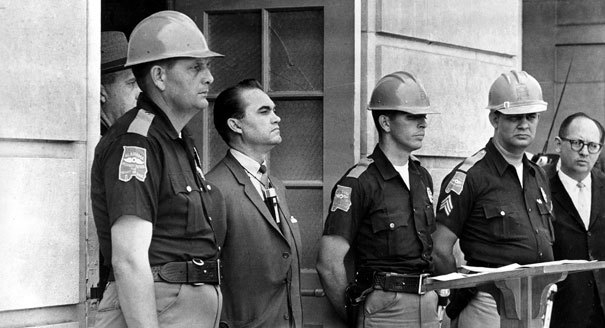

Similarly, the choices of curators in the Alabama State Archives Museum varied depending on the goal of the exhibit. For example, image choices, in particular, seemed to signal an effort to mediate between historical accuracy and more positive projections onto the past. Ramey, for instance, noted how the civil rights section of the museum presented the integration of Alabama’s public schools with an image of Bear Bryant in front of a desegregated student body instead of the infamous image of George Wallace standing in the schoolhouse door. While the Peace and Justice Memorial and the Legacy Museum confronted controversial historical moments head-on, the Archives museum took what some visitors might see to be a more round-about approach to tell a difficult story.