The blogosphere is lighting up in response to yesterday’s U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that some “closely held” corporations can be considered to have “sincerely held religious beliefs” (i.e., those of their owners, of course, and not those of their employees) worth protecting — and, voila, some corporations can now be exempt from certain aspects of federal law due to religious exemptions. (Read the so-called “Hobby Lobby” decision here.)

The blogosphere is lighting up in response to yesterday’s U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that some “closely held” corporations can be considered to have “sincerely held religious beliefs” (i.e., those of their owners, of course, and not those of their employees) worth protecting — and, voila, some corporations can now be exempt from certain aspects of federal law due to religious exemptions. (Read the so-called “Hobby Lobby” decision here.)

The interesting thing to me (something I wrote about previously, on another site) is the role played by religion in all this — no, not the role played by sincere religious beliefs and the right to freely express them, and no, not the role played by insincere or manipulative portraits of economic self-interest as if it were religious but, instead, the set of assumptions/set of institutional arrangements necessary to enable us to see either of these two narratives as relevant to our analysis of this issue. That is, the very storyline that the press and most protagonists (including the court) have adopted, as evidenced in the headline above (click the image to access the story), is itself the interesting thing in all this; for this issue doesn’t strike me as having anything to do with religion, belief, faith, whether sincere or not — and in saying that you must bear in mind that I don’t assume there’s some purer realm of faith that this issue somehow evades.

No; instead, all I mean is that placing the “religious rights vs. federal rights” narrative onto this issue, as if these were two separate domains that the court had to carefully balance, is itself the management move that we ought to be looking at, for adopting this approach obscures a simple (though not simplistic, of course) contest which is taking place over who is or who is not an authorized, legitimate social actor and which of their interests trump other people’s.

That’s all this is about.

That is, to gain an edge in this raw exercise of power by one group (in this case, corporate owners) against another (either the federal government, in this case in the form of so-called Obamacare, or employees), each side adopts what it sees to be a strategically useful self-image as marginalized victim in need of protection. And the discourse on religion is a key part of all this. For now we can portray an embattled group of authentic people trying simply to stay true to their own conscience in the face of the meddling federal government’s mandates or, instead, an embattled group of authentic people trying simply to stay true to themselves in the face of an irrational set of beliefs being imposed on them by their meddling employers.

Both sides in this liberal democratic dispute need the discourse on religion.

But no one is going to study the socio-politics of the rhetoric of religion here — i.e., we’re all going to keep on as if there is a pure realm of religion that is somehow different from politics (whether we privilege and exempt it or, in yet other cases, whether we denounce and combat it as radicalism and fanaticism, like some calling the majority on the Supreme Court “the American Taliban”) — because the larger discourse around it supports things we all take for granted and wish to marshal for our own benefit in a host of other situations — e.g., the notion of the individual as somehow being a socially autonomous, free agent; the notion of immaterial beliefs motivating observable actions; the presumption that some domain known as faith is unique and politically pure; the view that meaning is in the head and is only secondarily expressed in public, etc., etc. For to question all this, to see the so-called Hobby Lobby case as having everything to do with power, calls too much else into question.

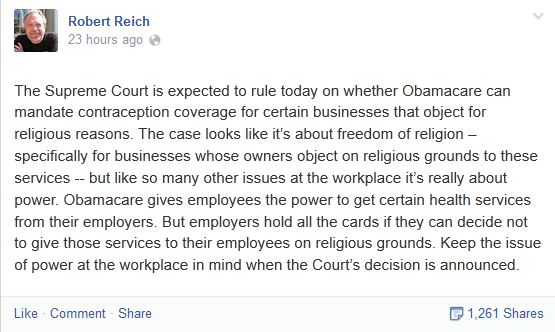

That’s why Robert Reich‘s analysis, posted on Facebook not long before the decision was made public, makes a lot of sense to me:

The rhetoric of religion, faith, and “sincerely held belief,” as used by parties on all sides, therefore all strike me as a strategic form of misdirection, preventing us from ever talking about the basic things actually at stake in these debates: i.e., who ought to be the authorized social actors, what agency ought they to have, and which of their interests can they exercise (and on whom)?

The rhetoric of religion, faith, and “sincerely held belief,” as used by parties on all sides, therefore all strike me as a strategic form of misdirection, preventing us from ever talking about the basic things actually at stake in these debates: i.e., who ought to be the authorized social actors, what agency ought they to have, and which of their interests can they exercise (and on whom)?