As a scholar in religious studies, my interest was piqued when a recent “The Daily” episode from the New York Times discussed community formation in Birds Aren’t Real, a movement / conspiracy theory that claims the government has replaced birds with drones to conduct widespread surveillance. The analysis of people who connect with others through Birds Aren’t Real had similarities to the ways that we discuss religions. Of course, connecting conspiracy theories and religion is not unique to me, as David Robertson highlights various connections in his research on UFOs and other conspiracy theories (listen to Religious Studies Project podcasts “Conspiracy Theories, Public Rhetoric, and Power” and “UFOs, Conspiracy Theories … and Religion?” for more, or read his book UFOs, Conspiracy Theories and the New Age: Millennial Conspiracism).

One potential difference from existing work on conspiracy theories and religion, however, is that Birds Aren’t Real is a parody of conspiracy theories. With the New York Times, the founder Peter McIndoe, who typically presents himself as someone desperately spreading awareness of the conspiracy, broke character to discuss the dynamics of his experiences in the satirical movement. Of course, he also has asserted that the media twists his words and disrespects the movement, returning thus to his role as founder of a conspiracy theory.

The participants, via social media, often appear to recognize the satirical nature. If you search #BirdsArentReal on Instagram, a lot of posts are photos of birds, typically in the genre of nature photography; some also simultaneously sport hashtags like #BirdsAreAwesome, #Birdnerd, or #birdphotograhpy, among others, at the same time. They are clearly celebrating being in on the joke (if I dare call it that, McIndoe may come after me). Participating in the community, for many at least, means knowing the truth of the parody, rather than the truth of the conspiracy theory.

This point raises one issue that we often discuss in the academic study of religion, is belief central or essential to religion? Many understandings of religion assume, often using Christianity as the prototype of religion, that religion is first about belief. What the followers of this religion or another religion believe becomes the most important question. The typical academic pushback is that, in many religions (religions generally, in my opinion), belief is less central than practice. What someone does is what defines them as a member of the community.

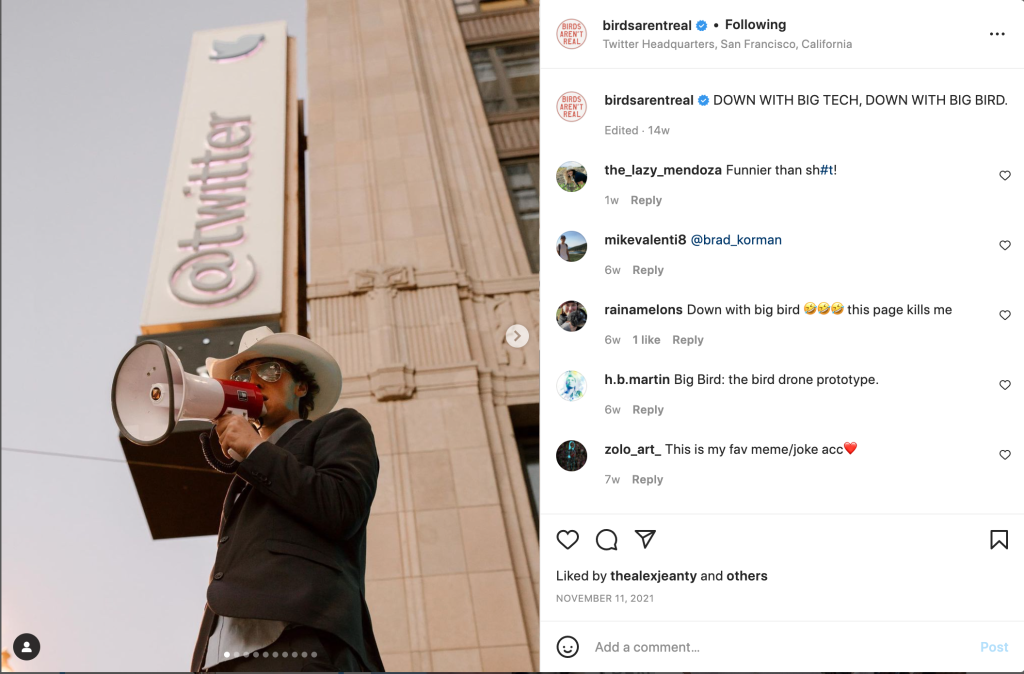

To apply this principle to Birds Aren’t Real, using the hashtag, being in on the joke, even participating in a physical protest outside Twitter’s headquarters makes one a part of the community. It is not really about belief. The belief that this movement is a parody, that birds are really real, is not what makes a person a member of the community, as many people believe birds are real but don’t identify with this group, just as most people see many conspiracy theories as fake (otherwise we call them simply conspiracies). I surmise that some commenters on their Instagram posts (see above post about the Twitter protest) identify with the community, but some commenters seem to remain on the periphery of the group. Identifying with the group, wearing their apparel (yes, they have tshirts you can buy), laughing about the joke, and using the hashtag are all activities that distinguish members of the group from others.

And that observable distinction is what is important, not what the individual assents to mentally. Identifying with the group presents oneself as someone “in on the joke”, connects with others who are similarly in on it, and highlights being opposed to harmful conspiracy theories (perhaps about pandemics or elections or lizard people, etc.). Having fun by implicitly mocking conspiracies that others promote builds a community identity. But closer attention to the social media presence extends this further. Some who use the hashtag #BirdsArentReal may be hoping simply to expand their network of followers and influence. One artist used the tag, alongside #birdoftheday and #prettybirds, to promote an enamel bird pin in their Etsy shop, a brewery seemingly randomly included the tag in one post, and tattoo artists promote bird designs with the tag.

To carry the comparison the other way, identifying as a member of a religious community can often be a matter of observable practice, wearing a symbol, participating in an event, displaying a religious identification on your business or automobile. These practices help distinguish the person from a non-member, which has various social benefits, especially if others in the same group have economic, social, and political power. In that sense, it is often not about belief in traditionally recognized religions but about observable identification.

Making this comparison does not imply that religions are conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theory is the label for someone else’s conspiracy that you think is fake. In that sense, conspiracy theory is a category to dismiss something, much like many use the term cult to dismiss a movement that they find to be out of bounds of traditional religion or beyond the reasonable. However, people label these movements, belief is seldom the most important category or element leading to identification with a movement.

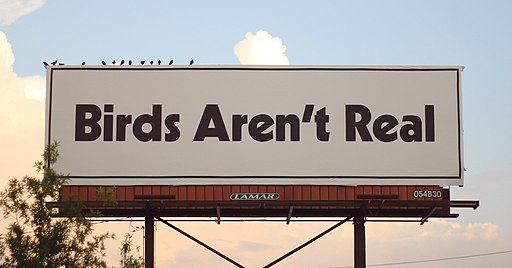

Image attribution: Andrewj0131, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons