If you’ve paid attention to the news in the US over the past week or so, you’ll know that a bomber was loose in Austin, Texas, and that the suspect was cornered by authorities the other day and blew himself up.

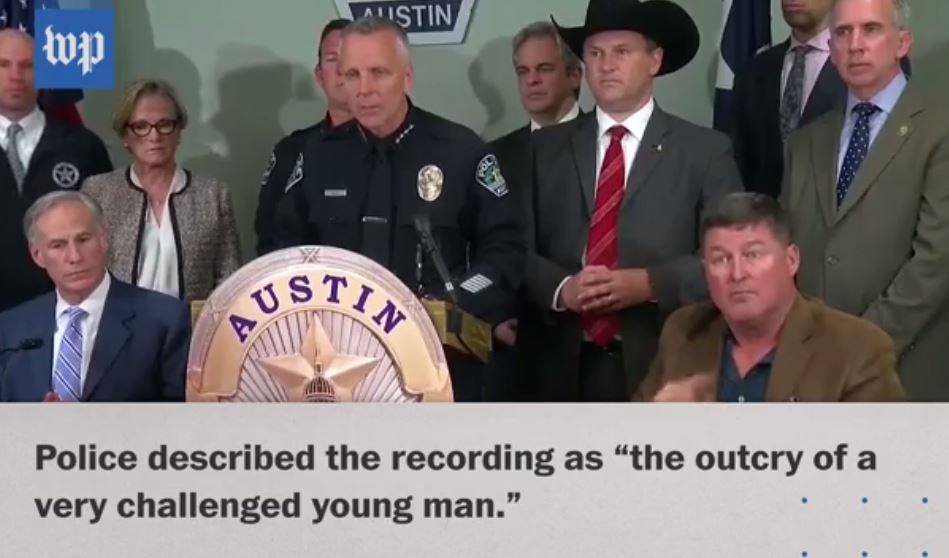

Apart from the bombings obviously making the news, what’s also caught some people’s attention is manner in which the local police have so far avoided labeling the man as a terrorist. Instead, after listening to recordings and video that he left, he’s been characterized by authorities as “a very challenged young man.” (Watch a video clip from the above-pictured press conference and read more here.) In fact, even the President was part of this effort to individualize the perpetrator(s) (rather that linking them to wider groups), prior to his capture/death, inasmuch as he had characterized the person(s) who might be doing this as “a very very sick individual.”

In response to this way of understanding the events (one that emphasizes individuality, illness, and youth), a number of commentators have — yes, once again — pointed out the general reluctance in much of our society to label crimes committed by white males as terrorism. For instance, consider this tweet (though, later, it should be said, white victims were certainly included):

Every person targeted has been a POC. Don’t want to jump ahead & call the culprit a terrorist, cuz you know… he might be white or something. And we all know white people can’t be terrorist. They are just lonely misunderstood wolves. ???? #AustinBombing #Terrorism pic.twitter.com/RyxefIw6jT

— MarianaNQ (@marianan) March 19, 2018

What I find interesting in all this is when we do (and do not!) sanction what scholars call an actor’s first person interpretive authority. For example, what now seems to be confounding police is that, in their reading, the suspect’s recordings don’t make any mention of terrorism or political issues (thus their reluctance, it seems, to label him a terrorist and, instead, the option of labeling him troubled or sick). But it is not difficult for anyone who watches a crime drama on TV to know that the disclosures of yet other suspects are treated as data in need of further, critical analysis, that is, their claims would be read rather suspiciously by authorities, as possibly lies or misleading and maybe even deluded statements that need to be interpreted rather than taken at face value as transparently sincere, self-aware, or meaningful.

While I’m sure the police will indeed chase down as much as they can in his claims, to try to piece together a way to understand his actions and motives (an understanding that may well deviate from how he himself might have claimed to understand them), what should attract our attention is this initial default assumption that some actors have the right to be seen as having command over their self-disclosures and intended meanings — their first person interpretive authority, in other words — while others certainly do not. How groups decide who ought to be seen as being in control of their own meanings, and whose meanings need to be decoded and problematized, is the interesting thing in all this — decisions that may indeed be affected by views many have concerning such issues as race and gender.

Perhaps this will be interesting to read too…

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/sympathy-for-white-austin-bomber-stirs-debate-about-race