Recently, a friend brought to my attention a 2015 article, by Amy Hollywood, published in Revista de Estudios Sociales, that takes issue with my work. The essay turns out to be an excerpt from what was then her forthcoming collection of essays (published in 2016).

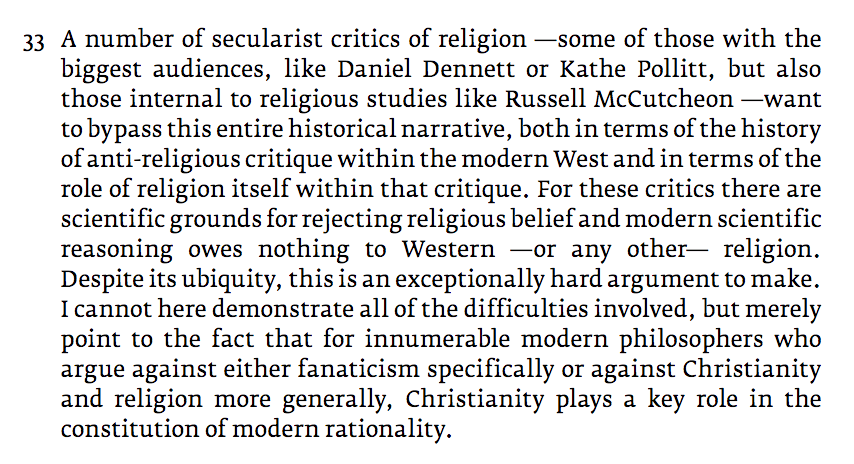

Although none of my work is cited in the essay (perhaps it’s cited in her book?), in two footnotes I’m mentioned as being among a group who are problematic in their approach to the study of religion. While in one I’m listed (twice, mind you) as being among the scholars that Tyler Roberts “takes on” in his 2013 book, Encountering Religion: Responsibility and Criticism After Secularism, the other footnote reads as follows:

Given that this is a blog post, and not an essay published in a peer review journal, I too cannot here demonstrate all of the difficulties involved, but suffice it to say that I don’t recognize my own work in this characterization. While I don’t think that I own the right interpretation of my writings, I do think that when we critique each other we at least ought to work hard to describe what the other says in a fashion that a writer might recognize their work, whether or not they agree with the criticisms that are then leveled.

But when I read that footnote, I don’t recall ever arguing that there are “scientific grounds for rejecting religious belief.” (No doubt there are plenty of people who might argue that, including Dennett, of course, let alone all those so-called New Atheists; but I don’t see my work as having much in common with them at all.) What I do recall arguing, on not just a few occasions, is that the public study of religion is a space in which we work in a particular way when it comes to such things as studying religion, and that, should one work in a private setting like Hollywood’s Harvard or Roberts’s Grinnell College, then one is free to do all sorts of things — from denouncing religion to advocating for overtly theological positions.

But inasmuch as all of those spaces are claimed to be scholarly, I’d hope that we nonetheless share certain standards for such things as how evidence is used in our arguments and how we read each other.

So it seems to me that, once again, I find a rejection of my work that strikes me as failing to actually understand what it is that I’m arguing. I’d love to see where I’ve made that claim or carried out my work in a fashion that made evident that it is intended to criticize religious people. Sure, I had the word “critic” in a book title once, and used it in some chapters, but I’d hope that careful readers can distinguish historicizing someone’s claim about the world (what I think that I meant by the role of the critic), on the one hand, and, for lack of a better word, criticizing it. (Unless, of course, self-identified religious people set the standard for how their words and actions must be understood by others [including scholars], in which case doing anything but repeating them back to them might be seen as undermining such people, I guess…) Sadly, quite a few in our field seem unable (or, better, unwilling) to make this distinction, as was painfully apparent to me in this podcast to which I was once asked to respond (something I made explicit in my response, in fact).

For whether claims about the world that many of us commonly call religious are true or not is just not a question in which I have any interest. Others do, to be sure, and they’re certainly welcome to pursue it in an institutional setting where people are able to entertain making, debating, and somehow adjudicating such claims.