Seeing cheering crowds in Miami, first thing this morning as I checked my phone for overnight news, celebrating Fidel Castro’s death, made me think a little about our disdain when there were rumors of people cheering after the twin towers collapsed (Trump routinely cited this early in his campaign); when is death — or better, whose death — worth cheering, I wondered?

Seeing cheering crowds in Miami, first thing this morning as I checked my phone for overnight news, celebrating Fidel Castro’s death, made me think a little about our disdain when there were rumors of people cheering after the twin towers collapsed (Trump routinely cited this early in his campaign); when is death — or better, whose death — worth cheering, I wondered?

But as the morning wore on and more news came out, my attention shifted to an issue that has long preoccupied me: our authority as scholars.

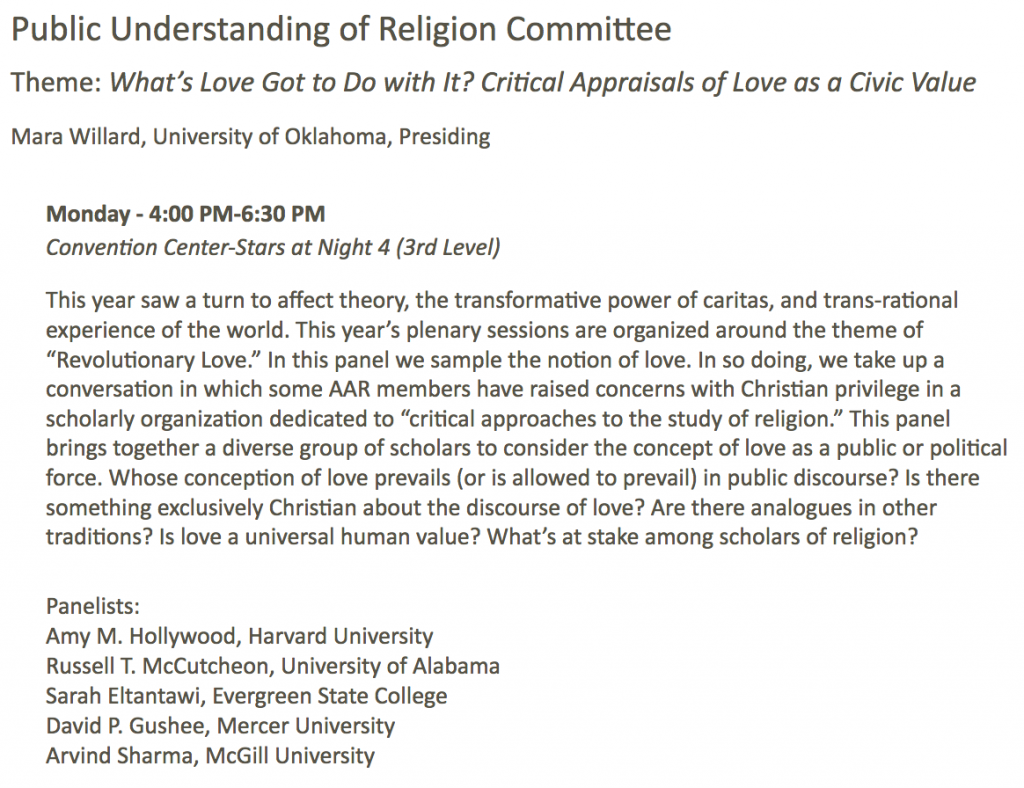

In fact, it’s a topic I spoke on last weekend, at our field’s main national conference, as part of a panel commenting on this year’s conference theme: revolutionary love. It struck me as entirely inappropriate for scholars of religion (but for liberal theologians, sure, why not?) for a variety of reasons, one of which was the problem of assuming that just because we study religion we therefore have something relevant to say about social issues, i.e., the ability to diagnose ills and provide remedies. For that’s what the panel was on: whether love was an effective political force.

My argument was that only if we misplace authority would we assume that scholars of religion have something to say on this topic. But if you assume religion is a deeply meaningful, trans-human kernel, then it makes sense why you’d assume that scholars of religion are a relevant source of input on these questions.

I thought of all this again, while listening to the radio this morning, as stories on Castro were broadcast. It was an interview with a History and Religious Studies professor at Yale that I have in mind, in which the “evil that he [Castro] represents” was discussed by someone who was forced to flee Cuba as a boy.

Give it a listen:

As I heard his institutional home cited at the story’s close I wondered to myself which hat he was wearing during the interview and if others even think it relevant to swap hats, all depending on the context and the conversation.

For on the panel I made that argument — while as a citizen, for example, I may have strong views on how society ought to be shaped, but inasmuch as I am a scholar of religion my role in these conversations is rather different — but was informed in reply by another panelist that not everyone has that luxury, of compartmentalizing their life as I had suggested. In the case of the radio story, the guest is clearly speaking as a participant in this history of dis- and re-location, but then the institutional designation arrives and I begin to wonder what to make of, for instance, his use of the discourse on evil. For I see it as a rhetorical term, of as little analytic use as the category love, and thus a term to be studied — who uses it, when, and to what effect — and not a go-to nomenclature to help me talk about the world in ways that elucidate it. But here, I heard the discourse on evil used not as I would, as a scholar, but as someone I might study would use the term.

Was I listening to a colleague or a participant, what anthropologists some time ago called informants? Why identify the institutional location of the person and, instead, simply name the book he’s written on the topic of the interview? Isn’t the latter sufficient?

Simply put, which credential is relevant when and for what reason?

It’s a minor thing, perhaps, but my sense is that the legitimacy of an actor is linked to little identifications like that, like a Victorian letter of introduction that paves ones way into new social circles. As scholars, we likely play on the authority lent by that diploma hanging on our walls in surprising ways — surprising because our credentials to study, say, the Reformation, can easily make us seem relevant to comment on virtually anything.

So are there limits to our relevance, as scholars of religion, or are we omnirelevant, inasmuch as we study religion? How you answer that might tell us much about the theory of religion with which you operate.