One night during my fieldwork among Brazilian migrant communities in Japan, I was invited to a dinner at Daniel’s apartment. He and his girlfriend frequented a local Brazilian evangelical church that I was studying. After the dinner, they started talking about the “strange festival” in Komaki, a city one-hour drive away from where they lived. The festival took place the previous week (on March 15 2014) and they came across its footage online. The Hōnen Festival at Tagata Shrine is best known for its 280 kg (620 pound), 2.5 meter (96 inch)-long wooden phallus, which is carried around on the streets during the celebration. The object is supposedly the embodiment of prosperity, bountiful harvest, and fertility. The youtube video above can give you some idea of what Daniel and Sachi saw.

“Nossa (Wow)! These women flock to the phallus and try real hard to touch it! They think they can get pregnant that way!” They exclaimed in a critical tone. Laughing hard at the whole comicalness of this festival, I responded, “Ah, c’mon, it’s just fun, that’s why most people try to touch it! Do you really think these Japanese women believe in it?”

“Yes!” They answered.

This exchange got me thinking afterward. I called my Japanese friend in the area, Hayato, who had actually been to the Hōnen Festival and asked, hesitantly, if he thought the phallic object could actually help people get pregnant. After a few seconds of laughing, he responded, “Well, I don’t really think believing in that thing is the point. It’s just that, you know, when you touch it and laugh with your friends, it gets fun. You feel more connected.”

It seemed that different people from different backgrounds interpreted the festival in different ways. Daniel seems to connect the participants’ action (i.e. touching the phallus) with a corresponding mental state or internal belief (i.e. “They think they can get pregnant that way”). Hayato, in contrast, suggests that the participants’ thoughts, opinions, and beliefs about the object are not really “the point” of the whole ritual.

Anthropologist Peter Stromberg, in his book on Christian conversion narrative, distinguishes between two diverging theories of language. The referential framework, he observes, dictates that words simply describe preexisting objects, entities, and situations. You say “I love you” because it refers to the feeling of love you already had prior to speaking. The constitutive framework, in contrast, grants more creative power to language by upholding that words create, change, and accomplish things in moments of utterances. If you think that saying “I love you” a lot is a foundation, and not a mere reflection, of a good relationship, then you agree with the constitutive view. Stromberg found that conversion narratives constantly shift back and forth between the two frameworks.

These frameworks can be applied to an analysis of ritual action as well. In supposing a preexisting mental state to the women’s action, Daniel invoked the referential theory of ritual: What you do stands for what you feel, think, and believe. Hayato’s view, on the other hand, resonates with the constitutive theory of ritual: What you do makes how you feel and who you are to others (i.e. “it gets fun. You feel more connected”).

Now, think about this: When you see a ritual, do you think about it in referential terms, or in constitutive terms? Maybe a mixture of both? As Stromberg himself notes, the dominant framework in American culture seems to be the referential one. Many people find it inauthentic to participate in something that does not reflect their own opinions, convictions, and beliefs. The constitutive theory of ritual, however, challenges you with an alternative view, in which the source of authenticity does not necessarily lie within one’s mental state but instead in the quality of social formation a given action facilitates.

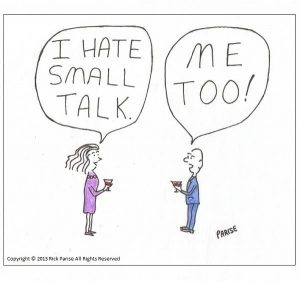

Next time you hear someone complain that she hates small talks because they are meaningless and fake, tell her that she could reconsider them in constitutive terms. Sure, small chats about the weather may not reflect how you are feeling at the time, but they nonetheless achieve genuine social recognition, i.e., “Hey, I acknowledge your presence; you are not invisible to me.” It is interesting that how so many of our small daily rituals— greetings, social smiles, small talks, etc.— share the same theory as the Japanese phallus festival: It’s not about what you believe but instead about what what you do does.

Notes: Parts of the post initially appeared in Japanologia, a blog run by Dr. Victor Hugo Kebbe at the Federal University of São Carlos in Brazil.