Last week there was some chatter online about the nominations put forward for the leadership of our field’s main professional association. (Question: why does the nominating committee exercise a monopoly on determining the organization’s leadership?) Apart from a variety of posts on Facebook and Twitter, the blogs I saw were those by Mike Altman, Aaron Hughes, Finbarr Curtis, and Elesha Coffman.

Last week there was some chatter online about the nominations put forward for the leadership of our field’s main professional association. (Question: why does the nominating committee exercise a monopoly on determining the organization’s leadership?) Apart from a variety of posts on Facebook and Twitter, the blogs I saw were those by Mike Altman, Aaron Hughes, Finbarr Curtis, and Elesha Coffman.

They’re all well worth reading.

The issue, for some, seems to be that the VP nominees are both Christian theologians of a particular stripe (maybe also their gender and race are relevant to some — just what criteria does this nominating committee even use?), leaving little difference between them and thus making a bit of a mockery out of the thought of choosing one over the other.

Sure, Coke and Pepsi are different in some regards, but…

I’ve not waded into this — apart from a few Facebook posts along with a couple private emails to some in AAR leadership positions, in which I expressed my views — because, well, to be honest, I don’t see all that much new here. For there are those of us who have been writing for quite some time on the problems of theology being seen as an academically legitimate pursuit within the study of religion. But despite this, it seems to me that this religious studies v. theology debate has, in the past decade or so (and especially with a younger generation of scholars), struck many as passé, yesterday’s news, so 1980s.

But now we see this tired old debate taking center stage once again.

But why now?

Before answering that — and as a way to hint at the answer I’ll give — I’d also ask why we weren’t up in arms for the past few decades when, some would say, this issue was no less evident? For instance, why did Don Wiebe — with whom I have some professional disagreements, sure, but not on this score — seem like such a lone voice when he chronicled, in great detail, the academic shortcomings of the liberal theological hegemony so prevalent within the leadership of the AAR? For example, see the chapters in Part II of the following volume (or click it to hear an interview with him).

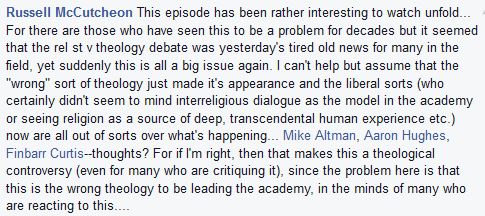

Of course I’ve answered these questions to my own satisfaction and concluded that there’s good reason why this is an issue now — as I phrased it the other day in a Facebook post on my own wall:

Of course I’ve answered these questions to my own satisfaction and concluded that there’s good reason why this is an issue now — as I phrased it the other day in a Facebook post on my own wall:

And that’s what so terribly ironic about all this, at least given how I understand it. For, despite appearances, this isn’t a debate over religious studies v. theology. Instead, it’s a theological controversy over which sort of theology — i.e., which sort of view on timeless meanings and human essences, along with the practical effect of each when realized in our world today — ought to be allowed to steer our professional society.

And that’s what so terribly ironic about all this, at least given how I understand it. For, despite appearances, this isn’t a debate over religious studies v. theology. Instead, it’s a theological controversy over which sort of theology — i.e., which sort of view on timeless meanings and human essences, along with the practical effect of each when realized in our world today — ought to be allowed to steer our professional society.

So, like I said, what so shocked some members, I think, is that these two nominees aren’t the right sorts of theologians.

It’s a problem of orthodoxy.

Which tells me that the fight has shifted from one over whether we were being historical or theological when doing our work as scholars of religion to one over which sort of theology — liberal or conservative, or what about evangelical? And what about people other than Christians?! — gets to count as legitimate in a scholarly field that claims to be public and empirical. If so, then for those of us who think the academic study of religion is something quite apart from elite participant reflection on the meaning or use of the faith, this episode is worth mulling over as we consider our own place in the field.