Vincent D. Jennings graduated in May 2020 from the University of Alabama with a dual B.A. in Religious Studies and Psychology. In the Fall of 2019 he began an in-depth study on America’s history of racial violence as part an independent study course with REL’s Prof. Theodore Trost — which culminated in this four-part series.

Between 1868 and 1871, a wave of terror swept across the South, resulting in the deaths of thousands of freed African Americans for simply asserting their most basic liberties; many were killed for simply walking freely on the streets while others were murdered for failing to obey the dictates of a white person during a random encounter. In response to this increasingly tenuous situation, legislators attempted to enact numerous levels of protection for African Americans. However, congressional efforts to provide federal protection and civil rights to formerly enslaved black people were undermined by the United States Supreme Court’s rulings, in cases like The Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1872); United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214 (1875); and United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876) (Lartey & Morris 2018) . It wasn’t long thereafter that Northern politicians retreated from the most significant and key pillar of Reconstruction: the commitment to protect freed black people. This unfortunate pivot resulted in the collapse of reconstruction soon thereafter while opening wide the door for cultural influences across the nation that bitterly opposed racial equality and once again this was especially true in the South.

Perhaps most symbolic of the collapse of Reconstruction was the 1877 Tilden-Hayes compromise. This was a compromise forged to stem the residual discontent from a razor-thin presidential election between Democrat Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford B Hayes. As part of this agreement, Republicans from the North agreed to withdraw federal troops from the last of the formerly renegade confederate states. Although this move technically only affected Louisiana and South Carolina, its impact was widespread across the entire south (and by extension the entire nation). For the South eagerly interpreted the troop withdrawal as a gesture that the north would no longer hold it accountable to its promise of full citizenship for freed black slaves and it took little time to resume its bitter resistance to racial equality (Lartey & Morris, 2018). Hence, in 1877, and as federal troops were removed from the region, there was a simultaneous reaction from white Southerners to mobilize their reclaimed power by barring blacks from voting, legalizing racial segregation, and constructing an economic system of sharecropping and tenant farming that would exploit African Americans and keep them poor and indentured for many generations. But perhaps the most vile and reprehensible fallout tied to the end of Reconstruction was that it ushered in the most notorious post-Civil War level of violence against African American’s: the lynching era.

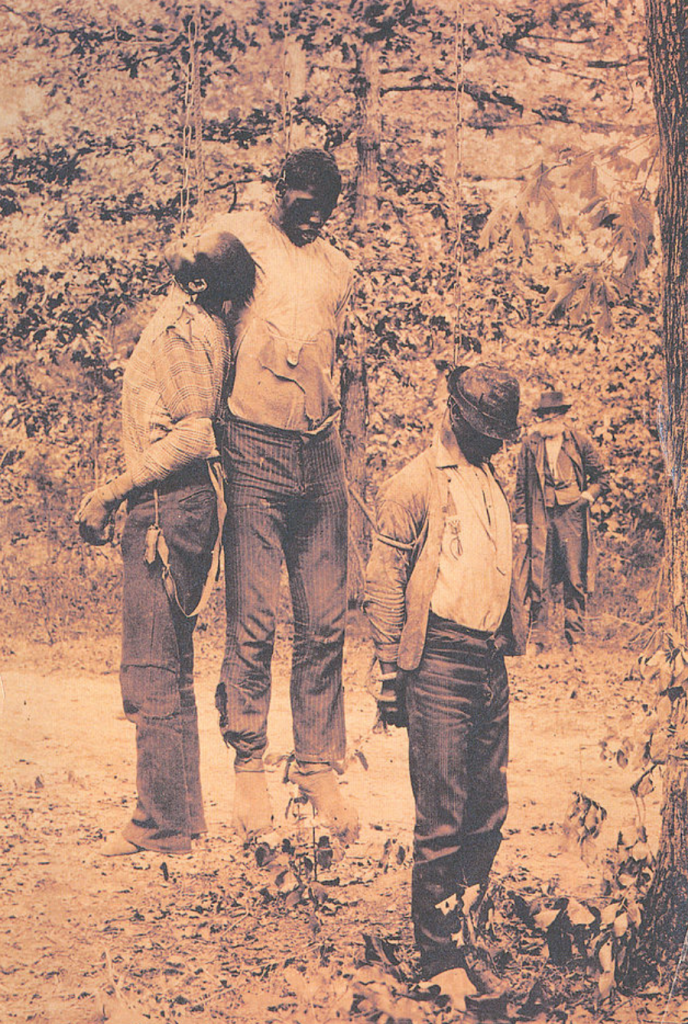

According to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), “lynchings were a method of social and racial control intended to terrorize black Americans into submission, and into an inferior racial caste position that was widely practiced in the U.S. south from roughly 1877 through 1950.” Because lynchings were typically executions outside the scope of official court proceedings and without any formal tracking system, most historians and scholars have little doubt that the true number of lynching’s in this country have been dramatically under-reported. Nonetheless, most of the more than 4,400 documented victims of racial terror lynching who were killed between 1877 and 1950 were killed in the 12 Southern states, with Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana among the deadliest. Several hundred additional victims were lynched in other regions, with the highest numbers in Oklahoma, Missouri, Illinois, and West Virginia. However, it is significant to note that there are countless other victims who were undocumented and remain unknown.

The concept of chattel slavery in the United States required manufacturing a myth of racial difference to justify the brutal practice of buying and selling African men, women, and children as property. The inhumanity of slavery was largely intolerable unless there was a narrative that enslaved people were not really people. However, once this was established as a societal norm there was no amount of subsequent military battles or legal developments leading to the abolition of slavery that could undo the caste system wherein it was appropriate to dehumanize blacks. Those ideas survived beyond the 13th amendment and were ultimately used to justify racial terror lynching through the criminalization of black identity. “Lynching soon emerged as a primary tool to enforce racial hierarchy and oppression while terrorizing black people into accepting abusive mistreatment and subordination” (Taylor 2019).

There was little pretense to hide the act of lynching African Americans; they were often committed in broad daylight and sometimes on the courthouse lawn. These types of racial terror lynchings were directly linked to the re-establishment of white supremacy and America’s history of the enslavement of blacks. Racial terror lynchings were different from the hangings and the mob violence committed against white people because racially motivated lynchings were intended to terrorize the entire black community, serving as a way to enforce racial hierarchy. They were also different than the type of “justice” committed in the early American west because, unlike the so-called wild west, racial terror lynchings typically occurred in communities with an already intact criminal court system — a system often viewed as “too good” for African Americans (Taylor 2019).

Typically, a lynching would begin with a criminal accusation being leveled against a black (most often a dubious accusation made against a black male), a subsequent arrest, and the formation of a “lynch mob” intent on subverting the normal judicial process or, expressed more directly, their intent was “to take the law in their own hands.” Despite its lawlessness and terrifying unpredictability, lynchings nonetheless had the unmistakable sanction of law enforcement and elected officials; as such, perpetrators were emboldened to act with impunity. Perhaps most disturbing was the fact that, once rumors of a lynching began to circulate, lynch mobs frequently were given the “green light” by law enforcement who would facilitate the wishes of the lynch mob by conveniently leaving a black inmate’s jail cell unguarded and unlocked, thus ensuring that mob justice would prevail without the benefit of a legal defense and before any formal trial could take place (Lartey & Morris 2018).

One aspect common to all racial violence, regardless of how trivial the allegation, was that once a violation was deemed to have occurred it was no longer satisfactory for the mob to merely carry out a heinous murder. Instead, the offense immediately escalated from the torture of a black victim for a singular offense into the symbolic discipline of his entire race. Hence, victims would be seized and subjected to every conceivable manner of physical torment, publicly tortured for hours, with the torture usually ending with the accused being hung from a tree and set on fire, before their brutalized bodies were left out on display to traumatize other black people. The unmistakable message was to serve as a warning to blacks everywhere: “do not challenge the supremacy of the white race” (Smead 1986).

Part 3 posts tomorrow

This is so wrong and when I saw that photo I was traumatized

The painful legacy of systemic racism and violence at the heart of the American story. Praying for their souls and the people of America. God bless us all!