So, I wrote a thing recently about how writing book reviews is not worthless.

So, I wrote a thing recently about how writing book reviews is not worthless.

But I got some push back concerning how some people in the profession, such as contingent faculty, don’t have the time or the ability to work for free by writing book reviews. I did say writing review was good for people at all career stages, after all, no?

I find this response lamentable, to be honest, because I don’t happen to think that writing book reviews is all about the review that results. In fact, even though that earlier post was written to contest some unnamed senior person who claimed that they were professionally worthless, the assumption that writing a book review is about the review (and so, is it really worth it…?) is a problem that many seem to share, regardless their career stage.

I don’t think its about the review, though.

Now, I also happen to think that studying religion is not about religion, whatever that may or may not be. Instead, the thing that we call religion is but a (possibly arbitrary) site for studying far wider things that are going on — like how people form and reproduce groups, how they contest each other, how they identify and rank their worlds, etc. The study of religion, among of the fields, happens to be a good way into all that.

So I think that writing a book review is a good way into a lot of other things that may (or may not) strike you as valuable.

So here goes….

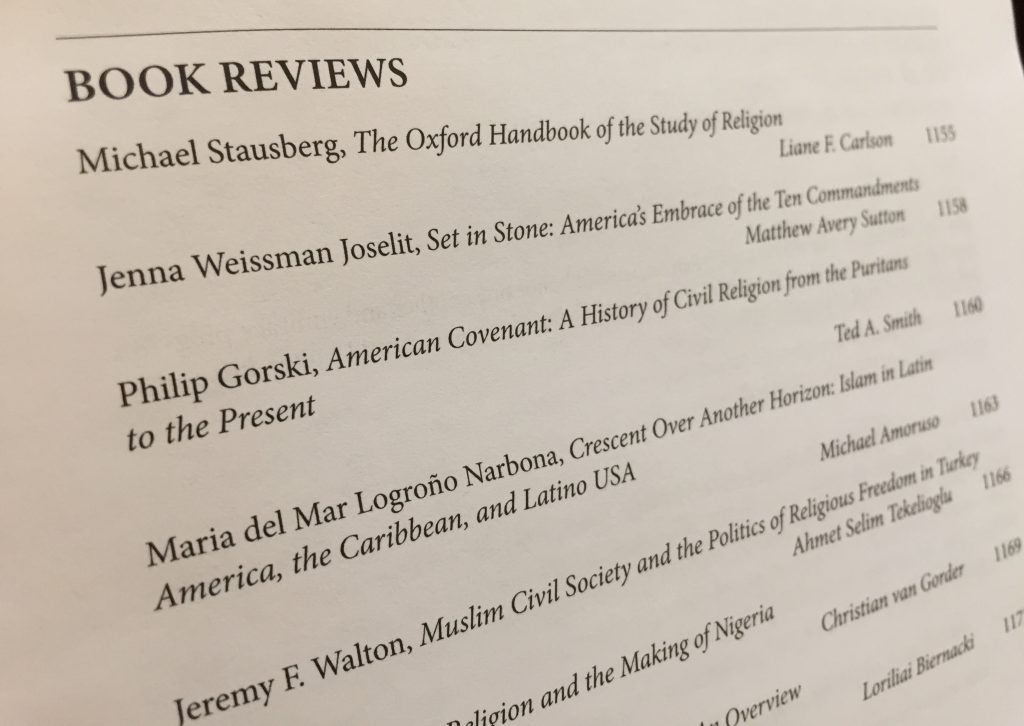

Minimally, it’s a free book, I guess, but, it’s also a line on your C.V. that says “I’m up on the current literature.” It’s not the only thing that can communicate that, sure, but until that far longer and more time-consuming essay or book manuscript gets written, proofed, submitted, peer reviewed, (more than likely) revised (if not rejected outright and then resubmitted elsewhere), and then copyedited, proofed, and published, a few book reviews can convey that you’re an active scholar. But maximally, its a little Petri dish — much as I think blog posts can be, by the way — where you can experiment with an idea that you’re working on, further developing your own angle on the material, thereby refining your opinion on what others are up to in their work.

Again, it’s not the only way to do any of this; but especially for busy early career people or people who have yet to land a full-time job or people not on conference programs (or who can’t afford regional or national conferences) and who, despite being busy contract lecturers (maybe even working at more than one place in the same semester), wish to stay active and hopefully competitive for far better jobs, it can be a strategic avenue to continue writing and publishing.

I think here of one of the challenges in this day and age of assessment: how to convey, to those outside your classroom, that you’re paying attention to your students’ needs and trying to help them succeed. Department chairs or more senior colleagues may visit your class once in a while, quietly sitting at the back of the room but sticking out like a sore thumb nonetheless, but they’re hardly there routinely, let alone those reappointment committees or Deans and Provosts. So if you ask me, the assessment initiative is actually a communications initiative because, in most cases, I’d like to think that the people teaching in university classrooms are highly trained, dedicated, creative, and hardworking, more often than not going far above-and-beyond the call to help their students. So mention of the word assessment shouldn’t result in us trying to invent new things to do with students but, instead, it should challenge us to figure out how to convey to audiences well outside our classrooms representative work that we’ve been doing all along.

Why did I go down that assessment road…? Because I tend to think that book reviews can work in much the same way.

Sure they benefit the field in a lot of ways (as well as help those book review editors who are always on the prowl for reviewers), but I think that they can benefit the reviewer way more than just being a free book.

For I assume that many of us are already reading new books on topics that are dear to us, on issues, regions, people or time periods in which we’ve each trained, in which we’re writing and on which we may be teaching. At my career stage I’m not looking for ways to persuade others that I’m engaged in the literature and that I’m eager to make a contribution, sure (so I might still be writing them for yet other reasons), but, much earlier in my career, writing a review on one of those books that I was already reading for other reasons, while I was teaching as an Instructor and trying to finish my own dissertation, was one relatively low cost way that I found to join the conversation and to communicate to others the work that was going on behind the scenes; and voila, some of that work may make it into print, someone might read it, and that much coveted line on a growing C.V. appears.

In fact, my first book review was published 5 years before I delivered my first major conference paper, which was also three years before my first published essay and — come to think of it — that first published essay was actually a review of a few books that kind’a got out of hand while I was writing it, and so I ended up writing a few thousand words. (It was on Eliade’s life and career, using his published journals and two-volume autobiography.) “Write to the editor and send them what you have,” a supervisor advised me at the time, “saying you’d be happy to shorten it but that maybe they’d be interested in a longer review essay…?” To my surprise, they took it. (Let’s be honest, they’re under pressures of their own and so they’ve got an issue to fill every quarter…) I now had a review essay to my name. And then I rewrote it as an appendix to my dissertation, to satisfy a committee member who was critical of my work and who wanted more info on Eliade himself.

That’s how my writing career started — and it benefited my dissertation (though it didn’t make it into the book version).

Sure, a dose of dumb luck needs to be added to that story and it certainly wasn’t the only thing that I was trying to do back then, and so yes, of course, I didn’t overdose on writing book reviews alone, but early on it was apparent to me that the book review was about so much more than the book review itself. It was practice in writing and argumentation; it was an early effort to meet and network with editors; it was additional experience with the world of publishing (the first copyediting and proofreading I got was, yup, writing book reviews); it was a professionally-sanctioned place to show the work that I was already doing; and, early in my career, it allowed me a place to start to develop that thing that we call our voice, the thing that continued to develop for some years, also through assorted other writing genres in our field.

(By the way, I hear stories of programs in the field whose faculty still advise against their doctoral students writing anything other than their dissertations and doing anything other than writing their dissertations. I can’t tell you how misguided I think this advice is.)

While realizing a seemingly simple book review may not do this for you, and while also recognizing that the conditions of higher ed have changed since when I was first on the job market in the early/mid-1990s (though job market pressures were not foreign to us as we graduated from our Ph.D.s back then — I changed countries to get a one year job as an Instructor, after all), I tend to think that the utility for early career people of writing book notes, book reviews, and review essays might now be more obvious than ever. (So long as a journal allows you to do it, that is, since some now require a Ph.D. in-hand or a doctoral student to have a letter of support from a supervisor — but I hear that Religious Studies Review is eager for new book noters and reviewers….) If, that is, we see that writing a book review is about so much more than the review that results.

So are there problems with the for-profit academic publishing industry and either pay walls to journals or outlandish subvention requirements? Yes, certainly. Are there problems with higher ed funding and the dramatic increase in reliance on contingent faculty? Yes, of course. Should tenure-track and tenured faculty work far harder to identify with and help their non-t track colleagues? To be sure. (I’ve written about that, in fact and we’ve long tried our best in the Department where I’m Chair.) But until we all figure out how to band together to make some of those structural changes (some of which require changing federal and state tax and spending policies), maybe the misleadingly humble genre of the book review can assist a few people who are trying to make strategic and wise use of their time and energy while contributing their voice to the scholarly conversation.

So yes, as I previously wrote, book reviews are a service to the field. But I also think that writing some can be a service to you — so long as you look past the review itself and see what else it might do for you.