Prof. Nathan Loewen specializes in the philosophy of religion and digital humanities among other things. This summer his research interests are taking him in a new direction at their intersection.

In Fall 2018, I took my research in a new direction. I began learning how to study the philosophy of religion with digital tools. The objective is to determine how to quantitatively test my qualitative argument that the field is historically structured by commitments to theism in ways that challenge its cross-cultural relevance. In the future, I plan to use these tools to locate underutilized opportunities to alter the scope of the field beyond theism.

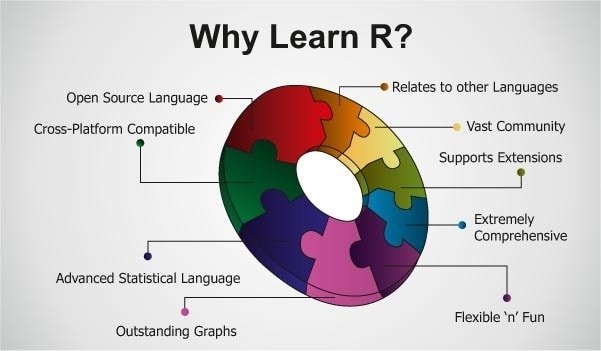

The tool is R, a language that is useful to perform various kinds of statistical analyses on large datasets. In the past academic year, I have signed a legal agreement to access a huge amount of data, agreed to collaborate with a Randall Research Scholar, obtained support of my department and a small grant to attend an intensive course on machine learning, and enlisted to attend an NEH summer institute on word vectors. The plan is to deliver preliminary results to audiences at Digitorium and a seminar at the American Academy of Religion.

How did this happen?

Since digital research methods did not figure into my graduate training curricula, my interactions with digital tools are organic (e.g. how do I embed the REL Twitter feed in my course page?). The organic approach supports my role as the faculty technology liaison for the College of Arts and Sciences, too, where practical issues drive projects like the Teaching Hub, OLIS and my participation in campus technology committees.

In that role, at the 2018 Digital Pedagogy Lab, I learned about the JSTOR Data for Research (DfR) site. I started clicking through the samples and began to wonder: what might be possible if I used this tool to study entire journals in the philosophy of religion? Could I create queries to investigate claims about the entire field? Could I zero in on specific concepts or topics? Could I find ways to discover patterns of relationships to other topics, concepts or authors? What if I could use this to detect lacunae, too? And, what if some of these gaps could be shown to have potentially productive relationships to scholarship being done in other fields?

The DfR site suggested using R or Python to analyze their data. I knew something about the latter and nothing of the former. Some searching around revealed a global community of people ready to share their expertise, as well as workshops at my university library.

What did I do next? I talked to people: librarians, faculty, students and my department chair…

An informal conversation with Sarah Whitver about my idea brought up the tragic example of Aaron Swartz. University libraries are highly sensitized to “data mining,” which turns out to be the type of project I was entertaining. I also shared this idea with my colleague Mike Altman, the REL undergraduate advisor, who suggested that I meet a freshman, Jackson Foster, who wished to add a religious studies major to an already impressive History major and minors in the Randall’s Research Scholars Program and Blount Scholars Program. Jackson sent me an email:

[Dr. Altman] mentioned a project relating to databasing journals for philosophy of religion utilizing R or Python. While I don’t know either at the moment, the languages I’m working through (and have, in part, mastered) at the moment— Fortran, SQL, and C#— would facilitate an easy transition.

The “data mining JSTOR project” showed potential. I asked my department chair, and Russell McCutcheon supported the idea. Jackson and I sketched out a plan for working on the project:

- Create a JSTOR DfR account and make a small request.

- Run some widely-available scripts in Python and R and create some basic visualizations.

- Work up a 2019 research schedule for an internal grant narrative.

- Find venues for possible dissemination of results in 2020.

- Consult with people on campus for advisement and resources using the above points for discussion.

The project really began to take shape after a conversation with Anne McDivitt at the Alabama Digital Humanities Center. The project looked entirely feasible. Her advice was to contact JSTOR and request a large, customized dataset.

The response from JSTOR was positive. To move ahead, I needed to provide a detailed request that outline the aims of the project, its scope and duration, our means of secure storage and disposal, as well as the projected outcomes and dissemination of results. Their legal team reviewed the request and sent us a legal agreement for the use of JSTOR data. The data was delivered to our secure storage on March 23.

The new direction in my research took shape between July 29, 2018 and March 23, 2019. “Analyzing Philosophy of Religion Journals Via Digital Humanities: Plotting Futures for the Field” is one name for the work Jackson and I will be completing in 2019-2020. By the end of that time, I will have far more proficiency in at least three Rs for humanities scholarship.