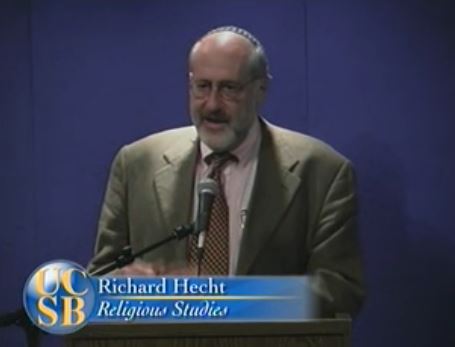

Richard Hecht, longtime faculty member at UC Santa Barbara, and onetime chair of their Department of Religious Studies, offers a reminiscence of the late Jonathan Z. Smith. Hecht is pictured above, introducing Smith’s 2003 Ninian Smart Memorial Lecture.

I met Jonathan and Elaine Smith shortly after they arrived in Santa Barbara in 1966 in one of the first courses he taught in the department. The war in Vietnam was heating up and President Johnson was guardedly increasing the number of American military personnel in the combat zone. The Selective Service or the Draft had not gone to its lottery system and used a system of classifications in the process of meeting the monthly national goals. A young man 18 years or older could be eligible for the draft and be 1-A; could be physically disqualified (my roommate took off the tip of his right index figure, his trigger finger, by sticking it under his lawn mower) and be 4-F; could be a full time student and be 2-S, as long as you maintained what your college or university considered a full course of study and were not in academic trouble; 1-D if a member of the military reserve like the National Guard or were a member of the ROTC; 3-A if military service would constitute a severe hardship to dependents, and several other categories, including for ministers and theological students. College and universities were required immediately to inform “your” draft board if there was any change in your student status.

I somehow found out that Jonathan was a conscientious objector and I think had won that status from his draft board well before the Vietnam war. I was considering applying for that status from my draft board, which bragged about never finding anyone who was a real conscientious objector, and went to him for help. He told me that he was working with Conscientious Objectors in a Quaker Fellowship Church. I began working with him, usually just taking notes on his conversations with young men on Monday nights from 1966 through Spring 1967. The Quaker Peace Fellowship and the Jewish Peace Fellowship were training draft counselors to help young men make the claim to conscientious objection, and to use the draft law to defend themselves against the draft and within jails if they had been arrested for failing to appear for induction. But as the war escalated and more and more men were required for the draft, fighting the draft board required some legal training as well.

We discovered that there was another Smith, William Smith, a young lawyer who was training draft counselors in Los Angeles. So we went together, I think Elaine must have driven us, because I don’t think I had a car and Jonathan was not driving at that time. Bill Smith (as he was known) won several very important cases against the Selective Service (one case of lesser importance was his successful defense to two anti-war protesters who dressed as army officers — General Hershey Bar (the head of the selective service at the time was General Lewis Hershey) and General Wastemoreland (General William Westmoreland was the military commander in Vietnam during the massive US escalation to over one half million military personnel) were arrested for impersonating military officers. Jonathan was a very serious anti-war protester — he regularly participated in a one-hour silent protest on campus here during the lunch hour. He gave some very powerful public speeches against the war that I recall and it seemed as if we were marching against war almost every weekend. After the war ended, Bill Smith continued to represent military personnel and won several important post-Vietnam War cases involving disabled veterans, as well as becoming one of the most accomplished labor lawyers in California. He died in 1999.