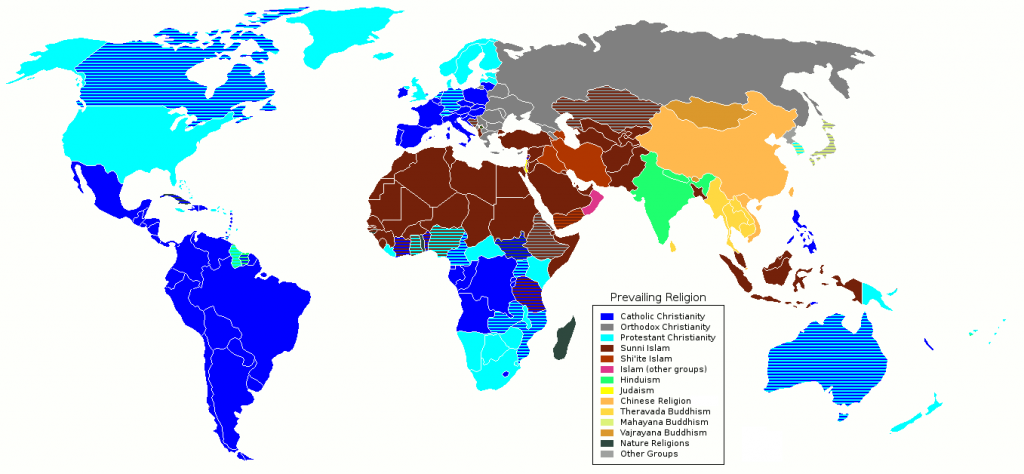

I’m writing this post during the office hours of my first REL100 course, “Introduction to the Study of Religion.” During the term, my 150 students were introduced to something they clearly did not expect: the study of religion. What did they expect? Something about this…

… in a context that looks something like this…

What happened instead? During my office hours, a student told me that taking my class was like learning from a “hipster version of John Greene.” Greene’s fast-paced videos on YouTube are among the ways and means today’s students learn about their course topics (As this student frankly told me, students sometimes use them as direct replacements for reading the text or showing up for class!).

John Greene’s 2 minute and 35 second “On Religion (Redux)” actually does a fairly decent job of presenting something about the academic study of religion.

The upshot of my course aligns with most of what Greene states here: a academic discussion about religion is a discussion about the vagaries of classification and the concomitant need for critical inquiry into how humans deploy grammar and classification.

My class sessions are structured as active learning based critical inquiries into how public and scholarly discourses deploy grammar and terms to frame “religion,” where examples from the everyday interact with those from religious studies scholars.

https://twitter.com/nathanrbloewen/status/664143001673998337

And so while the course includes a few lectures, several mini-lectures and many lecture-discussions to establish baseline arguments, students largely find themselves learning how to apply the ideas from the textbook and lectures in small group workshops. As a result, the class sessions regularly involve me and my amazing GTA, Dr. Paul Eubanks, floating from group to group in order to work out understandings of the course content and the example at hand. The image I tweeted below was a workshop where students discussed Canada’s proposed “Barbaric Cultural Practices” legislation.

https://twitter.com/nathanrbloewen/status/652192606827474945

Or, in another example from my course, groups first classified a list of 28 scholarly definitions of religion to be taking one of the following approaches: essentialist, functionalist or family resemblance. Each group then did the following while my GTA and I moved through the room to verify each group’s progress and results:

“The judgment of a classification is not “better or worse,” but whether or not it is useful. If this is the case, then classifications should be tactical and provisional. In other words, “religion” does not exist until an agent proposes a definition and theory of religion.

- Go back to the definitions and determine which are the top five most academically useful definitions.

- To the “approach” column, add what your group takes to be a good example of each “top five” definition from online media. Please both state the example and embed the link (press control+K to insert a hyperlink).

- To the “approach” column, add a brief justification of your chosen example.

My approach to structuring the course not only accomplishes the course learning objectives that are stated in my syllabus, it also fulfills what I think should be the pedagogical orientation of a humanities course that teaches critical thinking. As I state in a forthcoming article for Method and Theory in the Study of Religion reviewing the recently-released Norton Anthology of World Religions:

“There are several reasons why considering form as the first element of content is useful for teaching from a critical perspective (see Loewen 2015: 55-56). Doing so may focus course design on the skills for questioning subjectivity and interrogating the self-evidence of claims, for example. Learning objectives, then, are not so much to learn names and dates or memorable quotes… (see Zeller 2015: 124), but rather to demonstrate knowledge of how to analyze discourses according to distinct theoretical approaches. […] It is a normative claim in favor of applied learning, such that teaching constitutes the active facilitation of skills in the processes and procedures of scholarship.”

And so, compare all of the above to the approach taken by Jack Miles, the editor of the Norton Anthology of World Religions. I think you will agree that Miles articulates the common, folk sensibilities of what students thought an “introduction to the study of religion” would be about.

Instead, I do hope that my students come away from REL100 with a critical sensibility about all that goes into the construction of “religion.”