Occasionally I see a job ad, in our field, that has an open rank, stating that people at different career stages/ranks are invited to apply, or an ad so general that I’m not sure what the search committee is wanting.

Occasionally I see a job ad, in our field, that has an open rank, stating that people at different career stages/ranks are invited to apply, or an ad so general that I’m not sure what the search committee is wanting.

These ads strike me as rather problematic, for a few reasons.

First off, I don’t know how the search committee will compare applicants when virtually anyone can apply — it’s tough enough, to be sure, even when the pool is limited to people all entering the workplace of academia for the first time; for in that case the applicants can still differ widely: from those newly on the job market (maybe without their Ph.D. degrees in-hand yet and with very little to put on a CV) to those who have been on it for a few years, have been in yearly positions at a few different schools, have a tremendous amount of teaching experience, have already published their first books…

Or even their second.

Or third….

So, given the pressures of the job market these days, even searching within one rank results in candidates who are difficult to compare. But compare we must, since only one person will be hired; it therefore strikes me as being in our own best interest, as a Department that eventually needs to make what will likely be a tough decision, to work as hard as we can well ahead of time to think about and then narrow those variables and parameters as much as possible, so as to create conditions in which we can engage in some sort of reasonable, disciplined comparison once all the letters of application start coming in.

We are, after all, comparativists by training, no?

Searching for an open rank position or a position in which all comers might see themselves in the ad therefore strikes me as not just unreasonable, from a Department’s point of view, and poorly thought out, from a comparativist’s point of view, but also irresponsible.

Why?

Well, search committees and Departments are not the only actors in this drama — applicants play a rather prominent role themselves, since they’re the ones aiming to join our ranks. And while there inevitably are a number of unarticulated criteria in any job search — after all, only when one reads a certain CV, and sees certain credentials or work experience, might one realize that, say, a previously unimagined link with such-and-such a unit across campus, might be a great addition to the Department… — it seems to me that our responsibility to applicants is to articulate as clearly and concisely as possible what our needs and interests are, doing so right up front, in hopes that this helps prospective applicants to decide if this is an opening for them or, better yet, how to pitch themselves for it.

After all, it takes time and money to apply for a job and applicants need clear cues from us to help them decide if the investments are worth their while; given how terrible the market has been recently, from a candidate’s point of view, it’s not unreasonable to think of applicants applying to 10 positions annually, maybe 20 or 30, possibly more, so it’s no favor to them for us to search in broad or ill-defined areas — whether in terms of the career stage of the position or its topic/area. With the latter in mind, consider that weirdly broad Cornell ad now making the rounds on social media:

Or what about another current ad that looks for “either Religion and Science (preferably with strong grounding in theory) or Islam (area of specialization open but conversant with the modern period” (emphasis added); I have no idea how they’ll finally decide which of these two clearly unrelated desires they can satisfy with this one hire — perhaps someone who does the philosophy of science in modern Islamic societies?

Sometimes Departments do this (i.e., broad ads, wide open rank ads) for what they think are good reasons, of course — aiming to be inclusive, for instance. But no job is “come one, come all,” for members of Departments, and sometimes whole Departments in agreement, often have a pretty clear picture in mind of the sort of scholar they wish to hire, especially when it comes to their career stage. Usually the admin makes that pretty plain by setting the salary range before the search even begins, making clear that certain sorts of finalists are ruled out since they could never be paid what they’d expect or what they might already be earning elsewhere. For example, apart from my own hire, back in 2001 (I came to UA as a tenured Associate Prof.), I’ve never been involved in a search in our Department that was authorized to look for anyone but an entry level, tenure-track Assistant Professor.

And sometimes Departments do it because, at some schools these days, new or even replacement lines are so few and far between that they can’t help but throw every long unfulfilled desire that they have into the soup. For all they suspect that this is the last hire they’ll have for a while, so they go for broke and ask for it all; understandably (and lamentably), their eyes are far bigger than their stomachs.

But often I think Departments do it for less than well-meaning reasons: to avoid the tough in-house conversations that would result if faculty really had to discuss, openly and from the outset, what their hopes were for the future direction of the unit. Going on fishing expeditions, which is what I’d call some of these searches, can therefore be indicative of either a disengaged Department with absentee members (one sense of “gone fishing”) or one with internal divisions and controversies of its own, in which dissent must be suppressed in order to make the unit work from day to day, and thereby deferred (in suitably Freudian fashion) to a later stage in the hiring process — a suppression that benefits the current members of the Department, perhaps, by kicking the controversial can down the road a little further, but which hardly helps the many applicants who, based on little or vague public info, optimistically throw their hat into a ring where it really won’t end up competing.

It’s a problem I identified almost ten years ago in my “Theses on Professionalization“:

So while the ability to add an Associate of Full professor to the faculty, and not just an early career colleague, would be nice in many ways, I’d like to hope that I’d lobby hard to reject an open ad and, instead, decide as a group, from the start, which we were going after.

So while the ability to add an Associate of Full professor to the faculty, and not just an early career colleague, would be nice in many ways, I’d like to hope that I’d lobby hard to reject an open ad and, instead, decide as a group, from the start, which we were going after.

And, knowing the people I work with, I think there’d be a fair amount of agreement on that score.

After all, our faculty, here in Tuscaloosa, have decided on their own, and in broad agreement, no longer to conduct on-site job interviews at the AAR/SBL annual conference each November (since not all applicants can afford to attend and, besides, just what does one really learn about a person in a 15 to 20 minute meet and greet in a curtained room in a convention center?), opting instead for Skype sessions with what might turn out to be a wider variety of people. They’ve also stopped asking for letters of reference up front but, instead, just names of referees. We’ll ask for these letters later, and make some phone calls of our own, if we’re more seriously considering an application. Maybe it doesn’t make a big difference, but it streamlines the process for applicants and us (remember, not all applicants use pre-fab dossier services), simplifies what an applicant sends, and doesn’t waste the time of countless letter writers when, as it turns out, the vast majority of those letters are written for people whose applications, for a variety of reasons, don’t end up being competitive.

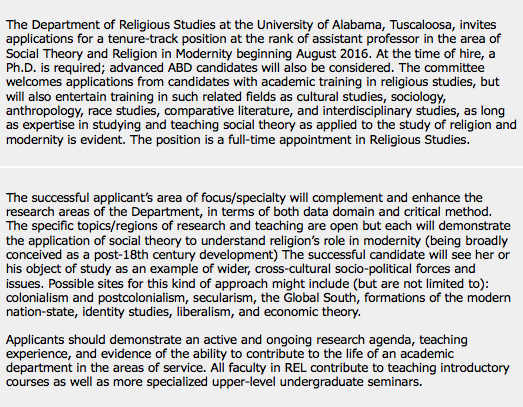

In fact, our Department has an open position this year, the ad for which went live just last week.

The rank is clear, and while there is obvious breadth in the possible areas where social theoretical skills are/can be used in our field (though we try to provide some concrete examples), my hope is that it is clear to readers that the requirement of being conversant with and then using social theory is clearly specified. The ad, as I read it, lists exactly what we’re looking for in terms of skills or approach and then basically invites applicants to visit our website to learn where we already use these skills, and then to convincingly portray themselves as strengthening our emphasis on theory by bringing new data domains to our classes — for the world is a really big place, of course, and we hardly cover it all.

The rank is clear, and while there is obvious breadth in the possible areas where social theoretical skills are/can be used in our field (though we try to provide some concrete examples), my hope is that it is clear to readers that the requirement of being conversant with and then using social theory is clearly specified. The ad, as I read it, lists exactly what we’re looking for in terms of skills or approach and then basically invites applicants to visit our website to learn where we already use these skills, and then to convincingly portray themselves as strengthening our emphasis on theory by bringing new data domains to our classes — for the world is a really big place, of course, and we hardly cover it all.

I’d therefore like to think that the parameters of the position are crystal clear while providing candidates with elbow room — an opportunity to freewheel within that domain, to persuade us of the importance and novelty of the site where they use the skills that are so important to us.

My point in all this?

The job hunt is an incredibly precarious and unbalanced power situation — yes, we all know that. And not every variable can be anticipated or specified from the outset. Yes, we know that too. But what can a Department do to interact as responsibly as possible with prospective applicants — especially when the market, for the majority of specialties in our field, is so heavily weighted in favor of the so-called buyers over the sellers of intellectual skills? That’s the question that, to me, needs to be asked and discussed. For a buyer’s market should make buyers who understand their intimate relationship with sellers work even harder, not less. And open rank fishing expeditions, along with vague and generalized ads, in which search committees seem to fail to make the tough decisions at the start and then end up browsing over large numbers of incommensurable applications, and then invoking empty words like excellence to narrow the field, don’t strike me as furthering that conversation.

Instead, they’re a barrier to us ever having it.