In May 2010 I gave a talk to some members of my campus’s Honors College about some possible directions for its future. I learned PowerPoint for the talk–I had, purposefully, never used it before. Although I started my fulltime teaching career (in the early 1990s) simply reading my prepared lecture–as I still do if invited to present a lecture at another school or if giving a paper at a conference–I then moved to using acetate transparencies and old overhead projectors to get a quotation or an image in front of students. (I still have a thick binder full of them that I once used in my 100-level intro class; and yes, I still remember what freshly mimeographed copies also smelled like.) Many of my peers were moving to PowerPoint, though, and, predictably perhaps, students were soon complaining to me about having trouble following my lectures.

By the time I came to the University of Alabama, in 2001, I was hearing from my students that some professors in the sciences would pre-post their PowerPoint slides and notes but with a key word missing here or there, such that taking notes in class meant listening at the right time for the missing word and writing it into the blank on your print-out of the slides. (If this was, and still is, a wide practice then no wonder we’ve all been plunged into a national preoccupation for improving teaching and proving results.) Grudgingly, I moved to using a Word document in classes, formatted in landscape and with large lettering, and projected onto the screen at the front of the room by means of the now omnipresent classroom multimedia system. It gave the students something to look at as I lectured, making them feel like there was something important to madly copy down into their notes; curious thing was that whatever I put on the screen was often already in their readings, sometimes word for word. Today, and I kid you not, they take our their smartphones and snap a photo with each new image on the screen. But the good students know my game and I rarely see them copying anything–instead, they listen and think.

On point of principle I have therefore avoided ever learning PowerPoint.

It has always seemed to me that my students were not just gaining information in my class–meaning that the artifice of an efficient and visually interesting information delivery system, as well as a way to replay the entire lecture at a later date via what we call a lecture capture system, was an impediment to my, as we now call it, learning outcomes. Instead, as I’ve phrased it in a few recent posts on this blog, my students were also learning how to learn. And giving them the slides in advance, taking full advantage of the stylish effects that PowerPoint has to offer, would further erode their need to pay attention and figure a few things out for themselves. As for replaying the lecture? Last time I checked, reality did not have a “do over” rewind button; I’d prefer someone come to my office hour with a question or two before I simply download the hard work of teaching to endless replays of my virtual self.

For the world, at least as I see it, is a complicated place and, in my class, I am data for my students to figure out. What will I test them on? What sort of questions will I ask? What was today’s main topic? And why did I show that clip from “Anchorman“? Although I give them clues and prompts, I’m hoping that they can start to learn that if it is mentioned in the book, if I talk about it, and if I write it on the board, well, they should pay attention to it. Education is, to borrow a phrase from Jonathan Z. Smith, a gradual introduction to devising and then taking responsibility for your own economy of signification–a way of learning to make sense of a world in which not everything can be equally significant. I figure that they come to my class in possession of a lot of commonsense, assuming that the important parts of reality are already highlighted for them, and my goal is, as I argued in a recent post, to complicate things and put them in the position of making choices concerning how they wish to move around in this modern world of ours. And PowerPoint, in my estimation, swims entirely in the opposite direction–even if some of the effects are really cool.

But as I said at the outset, I finally learned how to use it a couple of years ago. After an opening slide that showed my name etc., along with an image of the lovely columned building that is the home to The Honors College, and a second slide that summarized what I thought were the relevant goals in our campus’s 2004-14 strategic plan, my third slide read as follows:

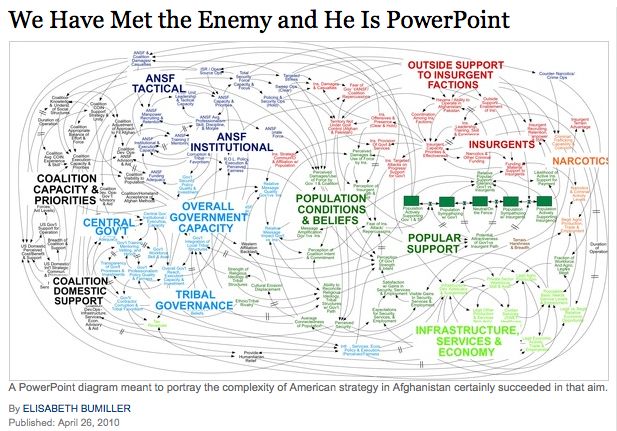

My third slide presented the following image, of U.S. counterinsurgency strategies in Afghanistan, from a New York Times article that had appeared just weeks before:

My third slide presented the following image, of U.S. counterinsurgency strategies in Afghanistan, from a New York Times article that had appeared just weeks before:

The slide’s caption, to go along with the image (a larger version is here), was a simple quotation from the article:

The slide’s caption, to go along with the image (a larger version is here), was a simple quotation from the article:

“‘PowerPoint makes us stupid,’ Gen. James N. Mattis of the Marine Corps, the Joint Forces commander, said this month at a military conference in North Carolina. (He spoke without PowerPoint.)” The New York Times Apr. 27/10, A1

My fourth slide used another quotation from the article to answer precisely why PowerPoint “makes us stupid”:

The fifth slide then read as follows, offering another quotation in the newspaper article from the U.S. military:

The fifth slide then read as follows, offering another quotation in the newspaper article from the U.S. military:

And the next slide simply had “So What?” written on it. At which point–did you see it coming?–I stopped using PowerPoint and started talking about the challenges in contemporary higher education represented by that handy software so many of us use in our classes.

And the next slide simply had “So What?” written on it. At which point–did you see it coming?–I stopped using PowerPoint and started talking about the challenges in contemporary higher education represented by that handy software so many of us use in our classes.

My point, which was hardly subtle and no doubt received in who knows how many different ways, concerned the role an Honors College ought to have on a University campus where the temptations to simplify are great, but I relate this story here to suggest the role the Humanities, as I understand them, ought always to have in a University education. When teaching a Humanities course–in fact, any university course, if you’re up to meeting the expectations of the Humanities–my advice is always first to think of what a PowerPoint presentation does and why you might make one for a class, and then to do the opposite.

It worked for George Costanza, and it might work for you.

You had me at “lovely columned building” !

Surprised? I am indeed more complex than one year of administrative service–though trying to teach English that its fancy new teleconference system was not a Skype system did take a few years off my life….

I completely agree with you on this one. A bit surprised to hear this coming from the eTech guy, but I’m a techie too and that doesn’t stop me from thinking critically about technology. PowerPoint does make people stupid, and learning how to learn is probably the most crucial outcome of a liberal arts education. And I too remember the smell of blue ink from those mimeograph machines. That smell used to make me enjoy writing math tests.