This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

This is an installment in an ongoing series on the American Academy of Religion’s recently released draft statement on research responsibilities.

An index of the complete series (updated as each

article is posted) can be found here.

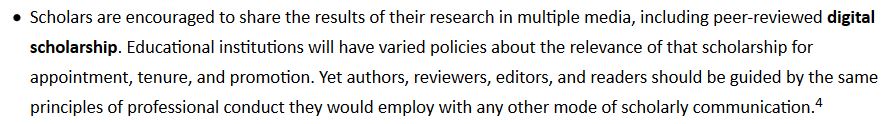

As with the eighth and ninth points of the draft document, the tenth also strikes me as unproductively redundant:

For while the previous two were both concerned with scholars talking plainly to wide audiences, this bullet point focuses on that too, but narrows in on the medium by which the committee seems to recommend we (increasingly) do this — online.

For while the previous two were both concerned with scholars talking plainly to wide audiences, this bullet point focuses on that too, but narrows in on the medium by which the committee seems to recommend we (increasingly) do this — online.

There is much to discuss here, not least being the fact that the digital medium is so new that it surprises me that the committee would go out on such a limb by devoting one of their meager thirteen statements on research responsibilities to this item in particular — especially when they acknowledge that the institutions in which their members work, and which, unlike a professional association, actually govern their career progress, have hardly taken a uniform stand on the relevance of digital publishing.

Although the committee hasn’t made a strong claim here concerning, say, scholars mainly or only publishing at open access sites (since that would implicitly require addressing publishers as their audience as well?), I nonetheless assume that this bullet point’s placement after the previous two means that they see digital scholarship as somehow being linked to the broadened readership they think scholars ought to be serving. (For, otherwise, why is this even included in the document — simply because “digital humanities” is now trending and catching the eye of granting agencies?) But, like I said, this medium is still so new — in its infancy, really, at least compared to the long established printed word — that it doesn’t strike me as a very responsible move to enshrine it today in a “top 13 list” of the researcher’s obligations. Wiser, I would think, would be to dwell for a moment on just what we mean by peer review and what we hope it can accomplish, before simply citing it as a necessary condition for helping to make this digital medium legitimate and, thus, I assume, scholarly.

After all, any idiot with a computer and a WordPress account can ramble on and on about whatever it is they like.

Exhibit A: this series.

So what does digital publishing contribute to the field? I don’t even want to count all of the blog posts I’ve written at different sites, since my first here, just about three years ago, but are they something I could cite in hope of career advancement? Or because I just log into WordPress and type away are they somehow something other than scholarship?

(Aside: Did such a thing as “scholarship” exist prior to the invention of what today looks like what we mean by the peer review process, usually dated to sometime in the 18th century? For all those classics we read, in our intellectual canon, weren’t assessed by means of peer review when they were published or repeatedly copied and circulated.)

And how will peer review help to regulate this?

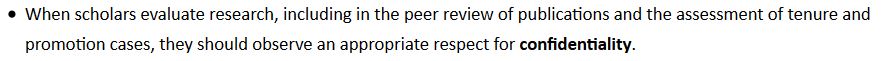

The eleventh bullet point (as well as a citation to a nine page draft American Historical Association report entitled “Guidelines for the Professional Evaluation of Digital Scholarship in History” — a document that actually tries to develop a rationale for its recommendations [something absent in the draft document under consideration in this series]) might help to shed some light on this, so I’ll consider it here as well, since it is explicitly concerned with peer review. It reads:

Sadly, this clears up little. In a document such as this, which aims to make a strong statement on our duties as responsible researchers, I’m surprised that emphasizing the confidentiality of the review process is all that the committee thought necessary to say about peer review — supposedly one of the few institutions that sets what we do apart as scholarship.

Sadly, this clears up little. In a document such as this, which aims to make a strong statement on our duties as responsible researchers, I’m surprised that emphasizing the confidentiality of the review process is all that the committee thought necessary to say about peer review — supposedly one of the few institutions that sets what we do apart as scholarship.

Presumably like the members of the committee, I’ve had my share of roles as a journal editor (in which I solicited and then used outside reader reports to determine what to/not to publish), and I’ve written assessments of papers for other journals and of book manuscripts for publishers, while, of course, also receiving my share of anonymous reader reports of my own work, so I can imagine far more than confidentiality that needs to be said about our responsibilities when it comes to how we judge our peers’ work. For the judgments that we group together as peer review end up constituting the field; they play a determining, or at least significant role (should editors listen to their referees’ reports, that is), in what gets published, what then gets read, and thus what is eventually cited, taught, and, possibly, added to the scholarly canon.

So a serious conversation on this institution is surely in order.

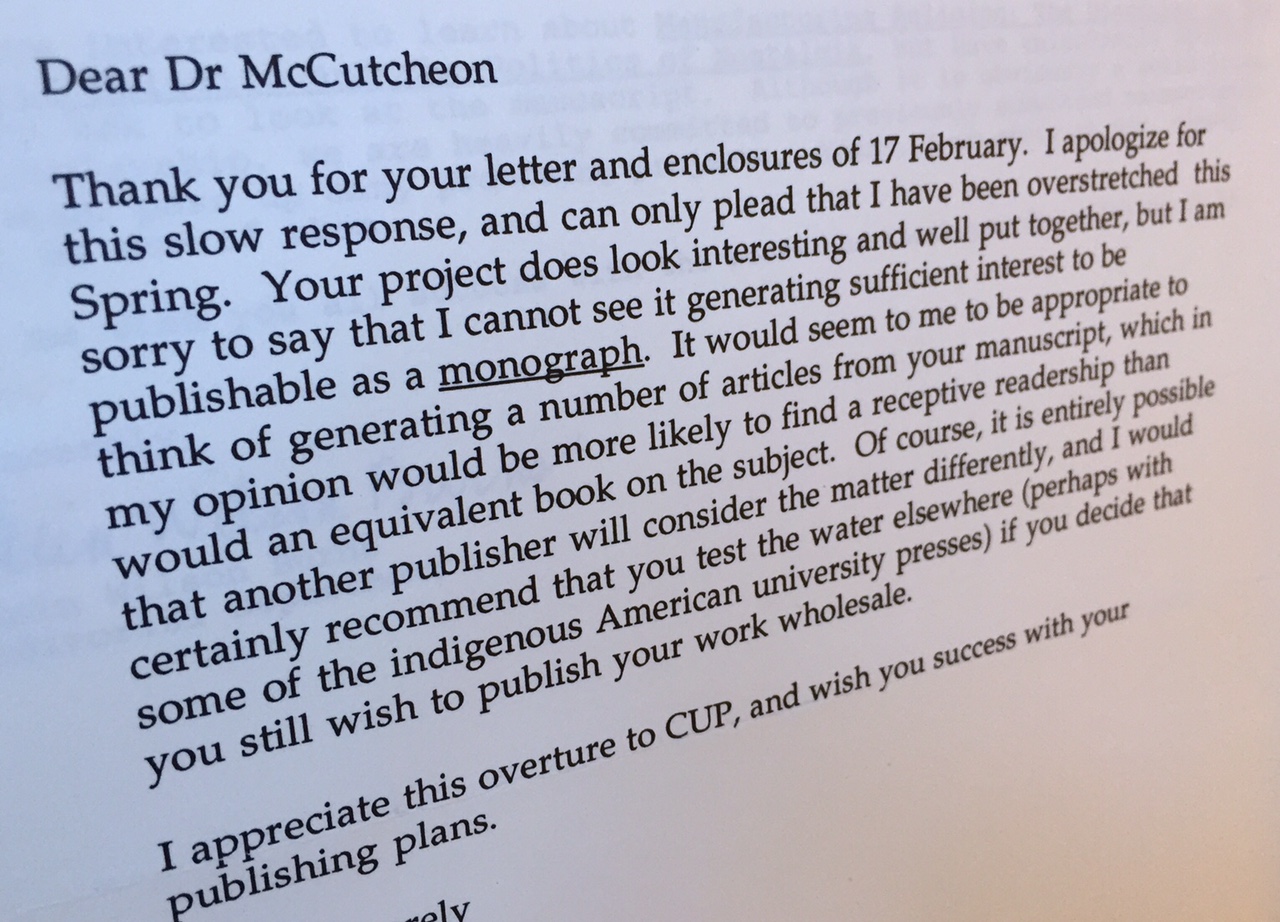

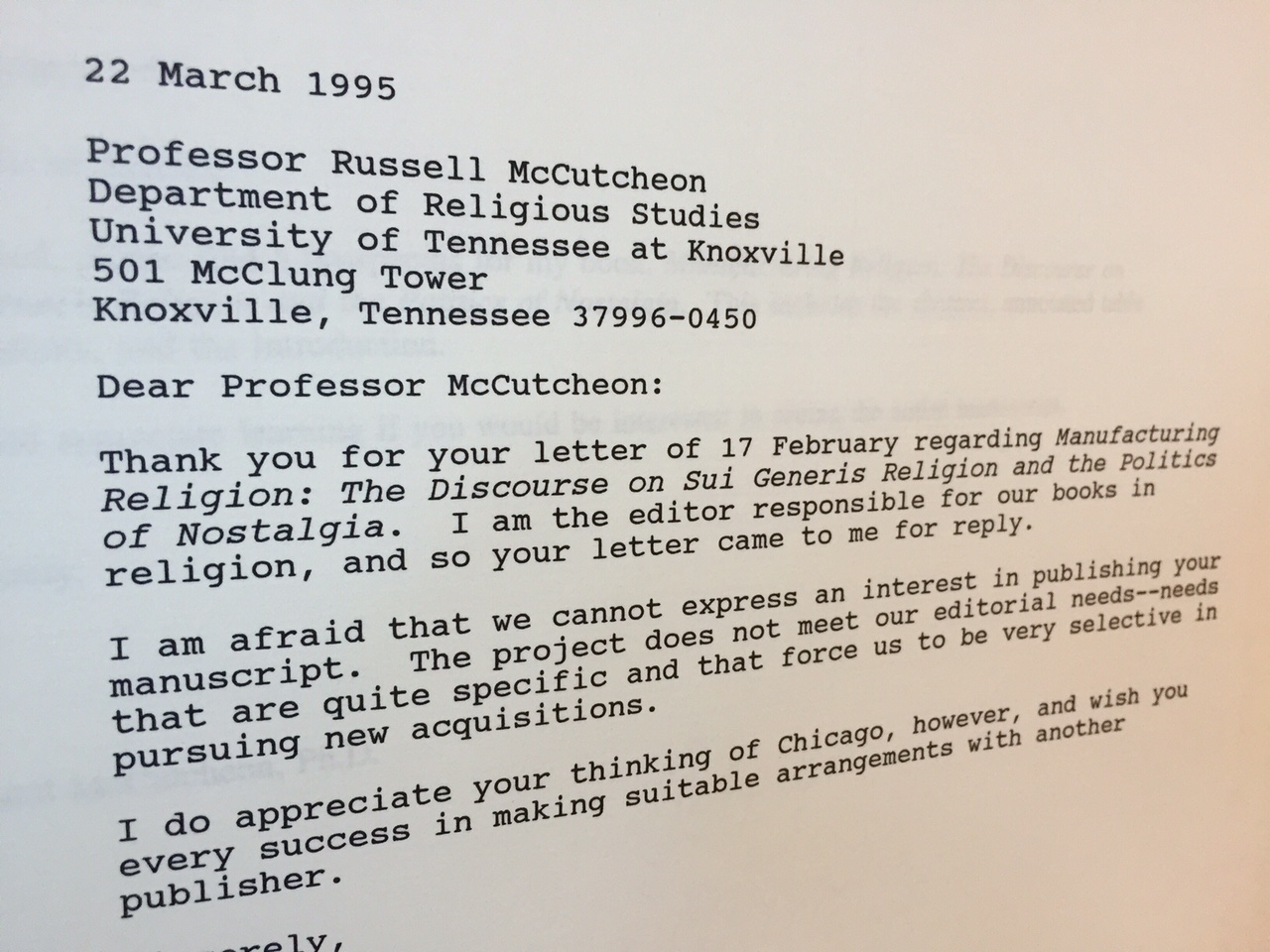

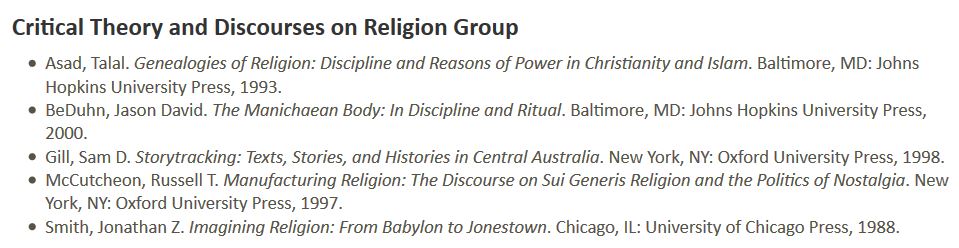

Case in point: while I could cite the comprehensive exam reading lists that grad schools use (for example, consider Chicago‘s, in just one of its areas), instead, consider that, just today, while writing this (it will not be posted for a few weeks), I read Richard Newton’s new blog post on the AAR program unit’s various suggested reading lists for each of their areas. In looking over the list — all books, presumably, that outside, readers were asked by publishers to assess prior to being contracted or published), I noticed one of my own — my first, in fact — listed by the Critical Theory and Discourses on Religion group. This provided me with a moment to sit back and consider how different my career might have been (different = non-existent, perhaps?) if Oxford University Press had declined seeing the full ms. (like all the other presses did when I sent each of them a prospectus after defending my dissertation in January of 1995).

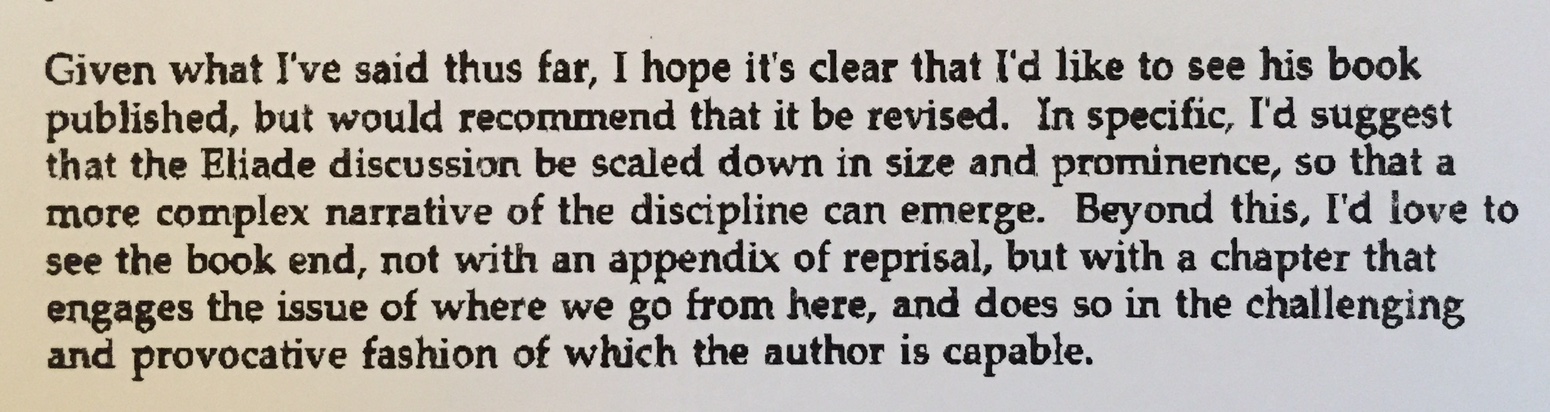

But more than that: what if OUP had decided to send it to almost anyone other than Bruce Lincoln for review? (He regularly makes his identity known, when reviewing manuscripts, so I feel it’s safe to name him here.) For, given the critique I had developed there, under the guidance of Neil McMullin and Don Wiebe at the University of Toronto, I can only imagine the majority of people at the time being, shall we say, unreceptive to the book (as was apparent in some of the critical reviews that appeared after it was published). For given that the book was largely devoted to a critique of the recent and contemporary field as it took shape in North America, I’d named plenty of current names of those whose work, I argued, exemplified problems that needed to be addressed. So the odds were stacked against that ms., in many ways perhaps, when it came to reviewing it. Peer review is, after all, an inherently conservative mechanism, given how a scholarly consensus usually exists (Kuhn called it a paradigm, of course) which becomes difficult to unseat. So, had it not been for Lincoln’s constructive review of the ms. — a scholar whose work I cited but who I’d meet for the first time only several years later — there’s a good chance it might never have been published, or at least not published in the form it was or by such a prominent press.

But more than that: what if OUP had decided to send it to almost anyone other than Bruce Lincoln for review? (He regularly makes his identity known, when reviewing manuscripts, so I feel it’s safe to name him here.) For, given the critique I had developed there, under the guidance of Neil McMullin and Don Wiebe at the University of Toronto, I can only imagine the majority of people at the time being, shall we say, unreceptive to the book (as was apparent in some of the critical reviews that appeared after it was published). For given that the book was largely devoted to a critique of the recent and contemporary field as it took shape in North America, I’d named plenty of current names of those whose work, I argued, exemplified problems that needed to be addressed. So the odds were stacked against that ms., in many ways perhaps, when it came to reviewing it. Peer review is, after all, an inherently conservative mechanism, given how a scholarly consensus usually exists (Kuhn called it a paradigm, of course) which becomes difficult to unseat. So, had it not been for Lincoln’s constructive review of the ms. — a scholar whose work I cited but who I’d meet for the first time only several years later — there’s a good chance it might never have been published, or at least not published in the form it was or by such a prominent press.

To make a long story short, without the decision on the part of an editor at OUP to seek, of all people, Lincoln’s opinion, it would likely have never caught to eye of any reader, let alone whomever it was who put together that list I mentioned above.

To make a long story short, without the decision on the part of an editor at OUP to seek, of all people, Lincoln’s opinion, it would likely have never caught to eye of any reader, let alone whomever it was who put together that list I mentioned above.

My point? It wouldn’t be difficult for someone to conclude that peer review is a euphemism for the crap shoot that is the supposed meritocracy of academia.

My point? It wouldn’t be difficult for someone to conclude that peer review is a euphemism for the crap shoot that is the supposed meritocracy of academia.

But while taking sheer luck (or whatever else you wish to call it) into account, I nonetheless think that peer review is a profoundly important though delicate institution that’s in need of continual care, for it is not difficult to subvert it: an editor can easily imagine to whom to send a paper to elicit a positive or negative review. What’s more, in my experience as an outside reviewer, there’s no guarantee that an editor or publisher will even listen to what a reviewer has to say about a ms. — many of us have had one positive and one negative review, only to see one of the two discounted, for who knows what reason(s), in favor of the other. And, as I’ve intimated in previous posts in this series, I’ve seen my share of reviews that read as flippant or dismissive and seemed far too brief to suggest that the referee gave the submission sufficient time and attention. I’ve even seen papers rejected because they didn’t “fit” the journal or the press’s publishing agenda. Case closed — no elaboration.

But given the difficulties journal editors and publishers not only have in finding people who will volunteer as outside readers but also make good on their promise to write a report (i.e., you put the peer in peer review), well…, editors will (understandably) take what they can get. For, at the end of the day, they need to fill up pages to mail out to subscribers.

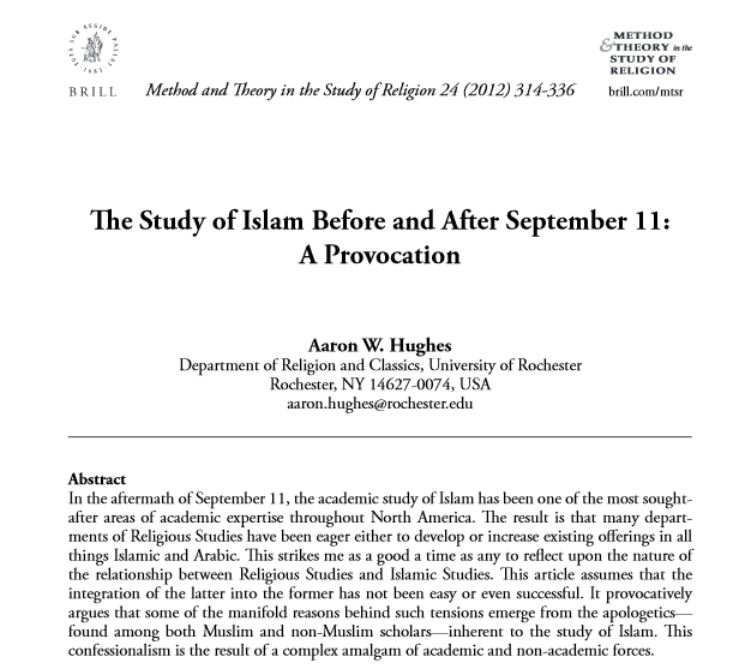

Come to think of it, a set of papers was commissioned and then published by MTSR a couple years ago (issue 24/4&5 [2012]) in light of what struck the editor then (Matt Day) as JAAR‘s insufficient review of an essay (by Aaron Hughes) it rejected.

As I wrote in the introduction to that set of papers (which all responded to Hughes’s essay):

As I wrote in the introduction to that set of papers (which all responded to Hughes’s essay):

Whereas one [JAAR] reader recommended publication outright (more on that below), others characterized the paper as poor, controversial, and even bordering on an example of so-called tabloid or even sophomoric scholarship. Day reasoned that, because Hughes is a respected scholar of religion who is widely published, by leading presses, in both the study of Islam and Judaism, printing this essay in MTSR along with invited commentaries from these same reviewers would allow readers to consider for themselves not only the state of Islamic studies within the academic study of religion but also how the so-called blind peer review process in our field functions, i.e., to consider the (often unstated but always policed) standards that determine what counts as scholarship (and what, on the other hand, is dismissed as, say, journalism).

That I was the one who recommended to JAAR that it be printed makes the story all the more interesting.

Although this post is hardly the place to have the conversation that I think these examples confirm that we need to have about peer review (i.e., on the responsibilities we owe to those whose research we evaluate, whether for publication, promotion, or grants, along with the responsibilities that editors owe to authors and which referees and authors alike owe to editors, etc.), let me make one suggestion for how to begin it: the committee should entertain making a strong statement on the need for double-blind peer review process to be adopted throughout the field. For I’ve too often received manuscripts where the author’s identity is either made plain on the title page or in which citations that accompany statements like “As I’ve argued in the past…” make it painfully obvious who the author is.

My concern is that while my identity, as an external reader, is unknown to the author (unless, like Lincoln, one declines that), I regularly know the author’s identity, and this strikes me as potentially undermining the institution that we rely upon to govern our field. A double-blind process, in which neither referee nor author know the other’s identity, is what is called for.

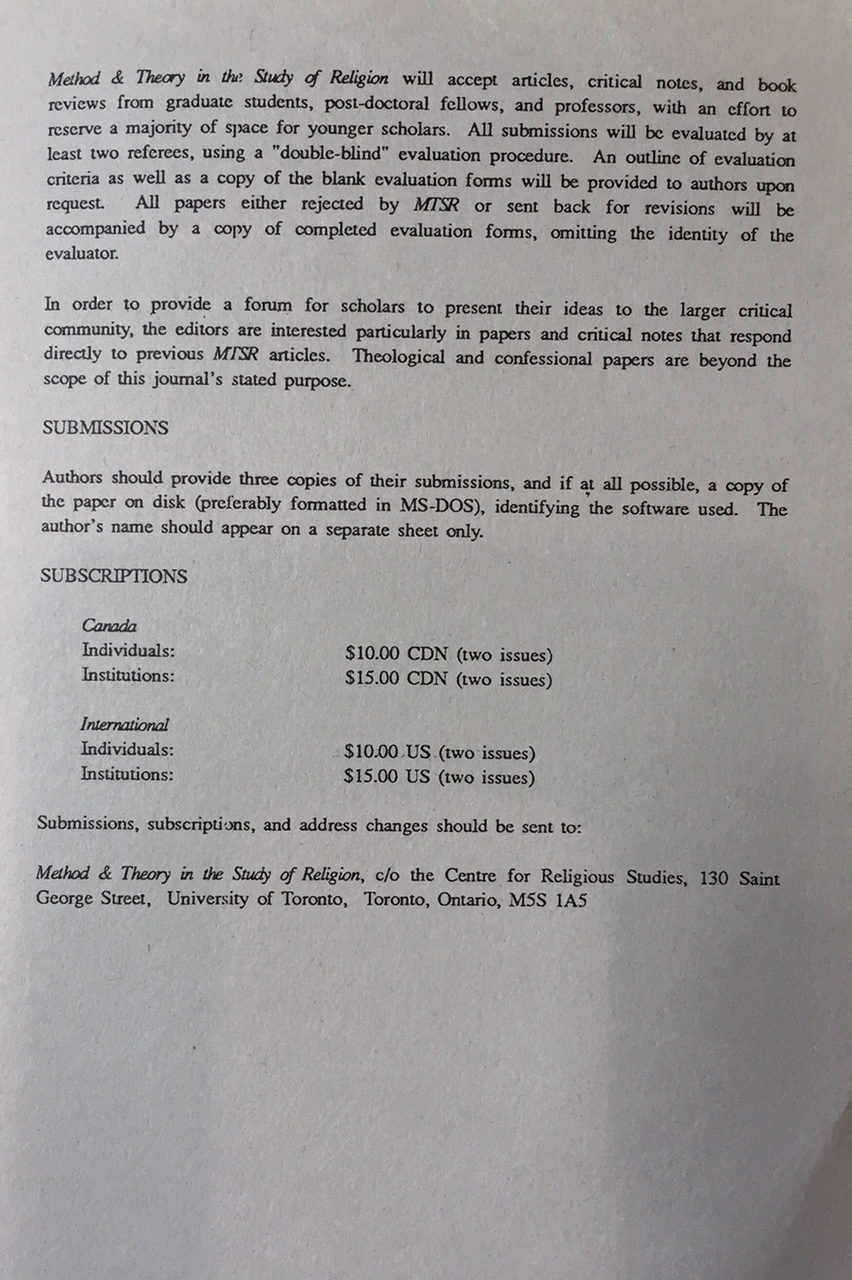

I think here, again, of Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, which used the double-blind process from the start (I began co-editing it at the end of volume 2, so this long predates my involvement); as described on the inside back cover of issue 1/1 (1989):

While I never asked the founding editors — classmates of mine — why they did this, I imagine it was, among other possible reasons, an effort to professionalize and authenticate what was then not only a brand new journal, edited by grad students, but one devoted exclusively to theory, and thus a periodical that might be easily dismissed by many more established scholars in the field. So ensuring that both author and reviewer were in the dark as to each other’s identities was one step toward ensuring that the arguments stood or fell on their own merits (or at least as close to this ideal as we can get) rather than on the reputations (or grudges) of the parties involved.

While I never asked the founding editors — classmates of mine — why they did this, I imagine it was, among other possible reasons, an effort to professionalize and authenticate what was then not only a brand new journal, edited by grad students, but one devoted exclusively to theory, and thus a periodical that might be easily dismissed by many more established scholars in the field. So ensuring that both author and reviewer were in the dark as to each other’s identities was one step toward ensuring that the arguments stood or fell on their own merits (or at least as close to this ideal as we can get) rather than on the reputations (or grudges) of the parties involved.

So whether or not we should all be publishing more online (Question: I’d be curious how much the committee’s members do this themselves), I think that we should first think about what constitutes something as worth publishing, worth reading, worth teaching, and thus worth shaping the field — whether it’s on paper or in the ether of the matrix.

Hello Russell, I did not catch this when I first read this article last week, but it’s misleading to think that peer review as a standard part of academia dates to the 18th century. It actually dates to the 1960s. For example, none of Einstein’s papers were ever peer reviewed, and Nature didn’t have peer review until 1967:

http://michaelnielsen.org/blog/three-myths-about-scientific-peer-review/

Peer review in the humanities likely came even later than 1967. What is its value in the humanities anyway, other than sociology and gatekeeping? When you think about it, the questions of whether it is possible to talk about “religion” in an objective way, and whether “peers” can help put useful bounds on it, raise all kinds of problems of exactly the kind you like to highlight. Widely celebrated scholars like Mircea Eliade and Huston Smith, who popularized the ideas of “world religions” and “religious studies” and continue to spark conversations within religion departments, would never have survived peer review in their own era, let alone today.

I was talking its historical origins and not just what we mean by it today, so for e.g., see note 2:

http://mcpress.media-commons.org/plannedobsolescence/one/the-history-of-peer-review/

Personally, I don’t mind entertaining that the work of the two cited scholars would not get published today. I’d call that progress. Wink.