Image by Thomas Nast – Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14640861.

Contemporary, anglophone philosophy of religion (PoR) may provide useful heuristic and therapeutic opportunities for religious studies as a discipline. How many years have critical debates about religious studies been ongoing? What proportion of RS scholarship might these debates occupy? Perhaps more than 1%? Have there been analogous debates about PoR? For how many years? My unproven hypothesis is that comparatively little PoR literature involves such debates. The lack of critical debates might correlate with Wesley Wildman’s findings that critical theory likely has zero significance among PoRs.

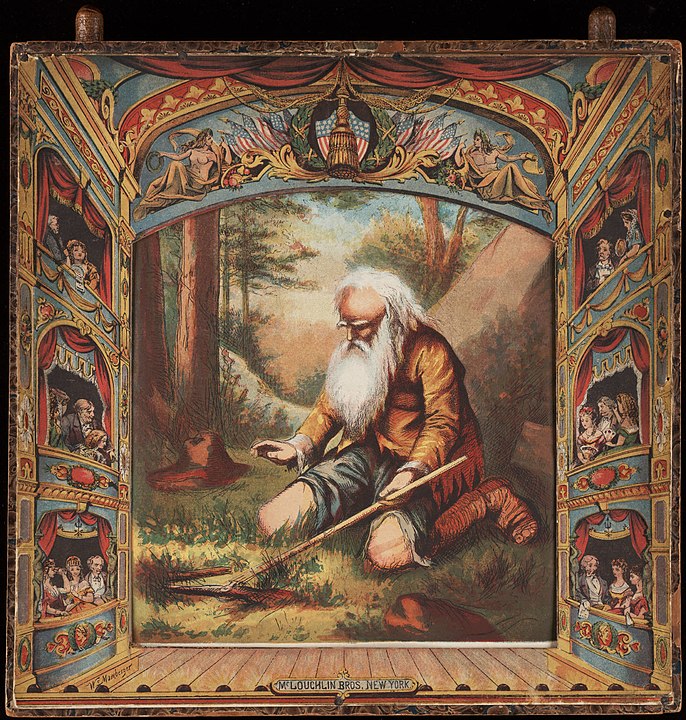

There are instances of nascent critical debate. In the 1980s, Frank Reynolds and David Tracy looked at developments in RS and thought PoR risked being old-fashioned. Religion and Practical Reason (published 1990) aims to show how Anglo-European emphases might give way to consideration of sources from around the world. Presuming now is a cutting-edge moment in the history of the field, PoR is Rip Van Winkle to the contemporary study of religion. This is not a bad thing.

Perhaps there’s an opportunity here to consider how Anglophone philosophy of religion intersects with religious studies debates about “critical” scholarship? I plan to develop this question to challenge the notion that PoR faces a dilemma of “disciplinary identity versus theory.” Can PoRs develop critical reflexivity in their scholarship and remain identifiable as PoRs? If the field does, might RS scholars benefit from observing the transformations of the field?

My questions were sparked by reading Galen Watts and Sharday Mosurinjohn’s 2022 JAAR article, whose title asks: ““Can Critical Religion Play by its Own Rules? Why there must be more ways to be “Critical” in the study of religion.” Might the article’s imperative for more ways to be critical include an apparently distant field of inquiry? I think it’s interesting to think about PoR as an overlooked counterfactual to ask what religious studies scholars really want for their field. Why does nobody on any “side” in the RS critical debates consider PoR whilst seeking resolutions to their debates?

I enjoyed reading Watts and Mosurinjohn’s article with PoR in mind. The text argues that a certain approach to religious studies, when taken to its logical ends, is inconsistent if not morally corrupt. The article uses “CR” to represent a body of RS scholarship with the following failures. CR: 1) practices historicization inconsistently 2) masks its own practices of normativity and 3) arbitrarily abandons self-imposed rules to avoid a) folk classifications and b) normative evaluation. The article argues that CR wrongly rejects scholarship that focuses on “the cultural structures, collective practices, and social performances that the term [“religion”] is used to refer to.” (331)[i] Thus, CR amounts to a quietism preventing academics from making normative claims about actual facts in the world. A counterfactual immediately came to my mind: what would such an article claim about “philosophy of religion”!

Over the past 50 years, very little PoR literature self-reflexively criticizes uses of the term “religion”. Emic understandings of demographically-dominant groups in the US, at least, will find the general upshot of PoR scholarship amenable: religious studies asks about God. Some PoRs argue that appeals to scriptural/doctrinal authority establish warranted belief. Other PoRs argue that private religious experiences are epistemological resources for the justification of belief in the afterlife. Paul Draper and Ryan Nichols’ 2013 study of cognitive bias and group influence in PoR finds the field’s arguments are, “too often evaluated using criteria that are theological or religious instead of philosophical.”

If that were the case, then all conventional PoR needs is a makeover: keep the interest in normativity that subdues historicization, but trade the field’s historic demographic composition and oft-parochial theistic orientation for other social identity markers and more global sources of apologetics. Perhaps only a lack of ambition stands in the way of opening options for RS to revalue PoR?

It cannot possibly be that simple.

Why would Watts and Mosurinjohn’s text not frame conventional PoR as another way of being critical? I can see a nexus related to historicism. Critical RS performs analyses of legitimation that involve historicization of etic meanings that brackets normative claims about actual facts in the world as etically described by stakeholder communities. PoR’s investment in normativity is an outcome of a primary interest in clarity and coherence. Analyses of justification involve logical grammars that separate etic use from semantic content precisely in order to clearly develop and apply normative claims. Stated otherwise, philosophical method foregrounds the tacit grammar of sense-making to develop the significance of reason-giving. Doing so filters for fallacies, questions presuppositions, and formalizes arguments, all in order to test the validity of justification. PoRs find history useful but not indispensable.

There is no debate in conventional PoR about “religion” because anachronism is not widely identified as a methodological risk. “There are no Rip Van Winkles here!” The systematic application of logic to develop conceptual frameworks is not worried about flattening history and culture. To adapt and paraphrase Bruce Lincoln’s condemnation of ahistorical scholarship: PoR expropriates cultural goods as grist for normativity mills.[ii] Thus, the PoR has no debates about the validity of the category “religion”.

Given the option, I suspect few religion scholars would say conventional PoR is an overlooked way of being critical. The approach has no methodological capacity to speak normative truthiness to power, if that’s what is missing from so-called “CR”.

Where critical approaches draw on conventional philosophical tools to develop their positions, they likely reject PoR’s lack of historicization. Where RS scholars may appreciate PoR’s capacity to make normative claims, they likely reject the thin approach to history and culture. Conventional PoR thereby offers a ready case to test what RS really want when they’re searching for “other ways to be critical.”

[i] That discursive battles about “religion” fits within these latter categories is an observation, but not my point. The concluding sections of Watts and Mosurinjohn (2022, 331-2) ask “what does it mean to be critical?” The question’s ontological premise is interesting: presumably a scholar can assume a social identity, thereby saying “I am critical.” That’s a different question from “how might a scholarly text be understood as critical?” One question is about social ontologies, the other is about understanding.

[ii] “When scholars treat the complex products of another society’s imaginative labors as the raw materials from which they conject their theories, and when they regard their theories as an intellectual product of a higher order than that of the materials they extracted, grievous abuses have been committed.” (Lincoln 2018, 9) Interestingly, this objection is not raised by Christians, who never find PoR’s overwhelming focus on theism to have exploited Christianity.