Vincent D. Jennings graduated in May 2020 from the University of Alabama with a dual B.A. in Religious Studies and Psychology. In the Fall of 2019 he began an in-depth study on America’s history of racial violence as part an independent study course with REL’s Prof. Theodore Trost — which culminated in this four-part series.

Of all the violations deemed worthy of lynching an African American, no offense or accusation stirred the level of vitriol and incited the level of violence more than the suggestion of sexual contact between a black man and a white woman. It required little more than a rumor based upon a whisper against a black for the result to end in a lynching. The trope of the lascivious hyper-sexual black male served as the basis for the most incorrigible acts of “retribution.” Sexual contact between a black male and a white woman (occasionally real, but usually imagined) often involved as little as a black man accused of failing to keep his eyes on the ground in the presence of a white woman. For the lynching era emerged on the scene at the same time that Jim Crow and racial integrity laws prohibited social interactions between people of different races. The fact that the violations were always perceived to occur in relations between black men and white women (but seldom between white men and black women) speaks to how “this trope regarding the hyper-sexuality of black men especially vis-a-vis the inviolable chastity of white women, was and remains one of the most enduring tropes of white supremacy” (Lartey & Morris, 2018).

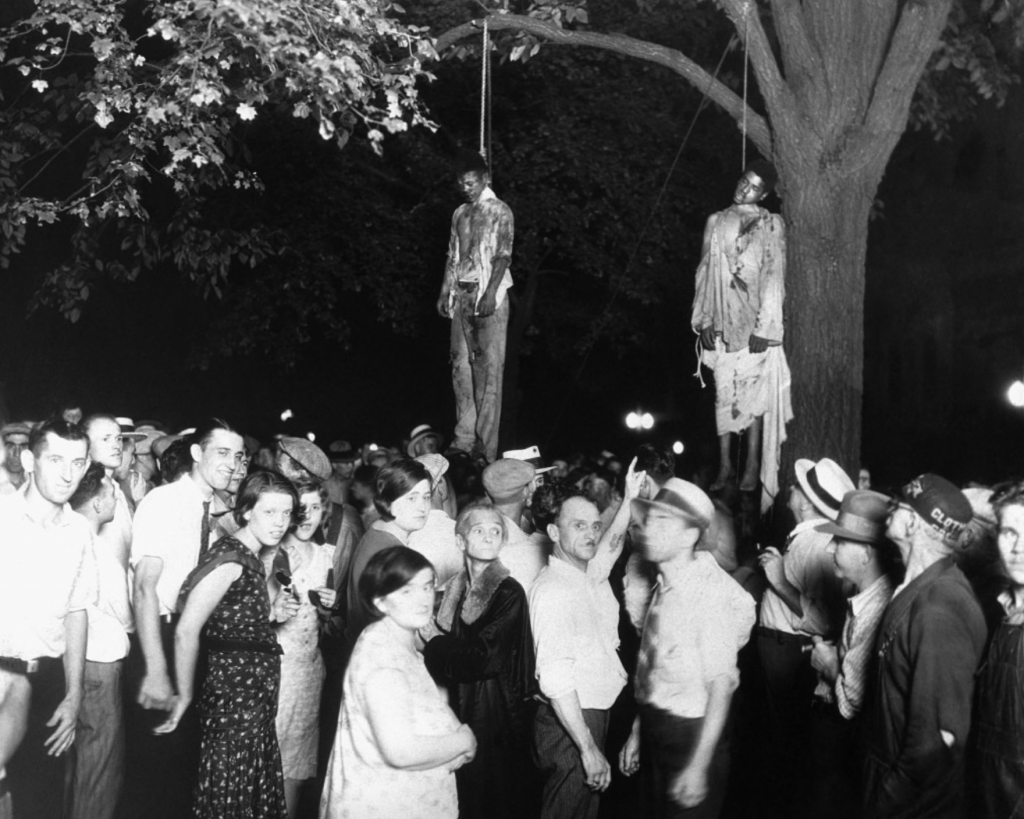

One of the more disturbing and “unsettling realities of lynching is the degree to which white Americans embraced it,

not as an uncomfortable necessity or an unfortunate means to an end … but rather as a joyous moment of wholesome celebration…. Whole families came together, mothers and fathers, bringing even their youngest children. It was the show of the countryside – a very popular show, read a 1930 editorial in the Raleigh News and Observer. Men joked loudly at the sight of the bleeding body [and] … girls giggled as the flies fed on the blood that dripped from the Negro’s nose. (Lartey & Morris 2018)

In the 1931 lynching of Raymond Gunn in Missouri, one fourth of the crowd’s estimated tally of between 2,000 to 4,000 revelers was comprised of women and included hundreds of children. Typical of the sentiment of the era, one woman was reported to have “held her little girl up so she could get a better view of the naked Negro blazing on the roof” (Raper 2003).

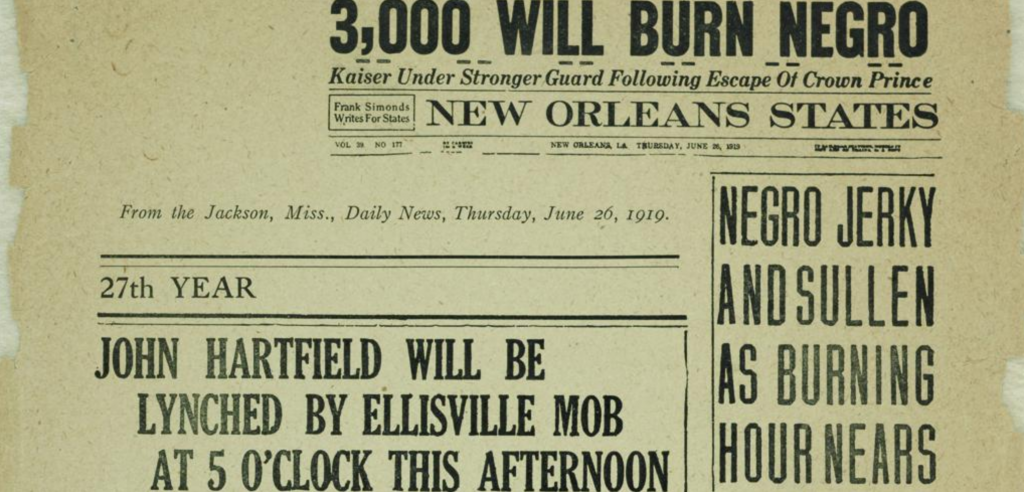

While sexual offenses ranked clearly as the most impassioned reason for deadly vigilante violence targeting black men and terrorizing black communities, “[o]thers were lynched for simply refusing to address a white man as ‘sir’ or demanding to be served at the counter in a segregated soda shop … or for ‘standing around’… or ‘annoying white girls’… or for failing to call a policeman ‘mister’ (Levin 2018). For example, in Labelle, Florida, in 1926, Henry Patterson was lynched for “attempting to assault” a white woman; soon after his death, news emerged that his “offense” had actually been asking for a drink of water (Taylor 2019). Reporting on the lynching of a black man in Millersburg, Ohio, in 1892, an Indiana newspaper explained: “He had lingered about people’s doorsteps and annoyed them in various ways. There are supposed to be no Negroes in Holmes County.” William Brooks was lynched in Palestine, Arkansas, in 1894 for asking to marry his white employer’s daughter. In 1930, a 65-year-old black woman named Laura Wood was hanged with a plow chain in Barber, North Carolina, for allegedly stealing a ham. Hundreds more black people were lynched on allegations of arson, robbery, non-sexual assault, and vagrancy (Taylor 2019). In his autobiography, W. E. B. Du Bois writes of the 1899 lynching of Sam Hose in Georgia, that the knuckles of the victim were on display at a local store and that the state’s governor received pieces of the man’s heart and liver (Lartey & Morris 2018). Indeed, it was not uncommon for victims to be dismembered as mob members would vie to acquire pieces of flesh and bone as souvenirs.

Heading into the 20th century, brutality against African Americans began to trend more mainstream, as national leaders and media outlets quickly learned to use white supremacist views and pro-lynching rhetoric for political gain. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt declared, “the greatest existing cause of lynching is the perpetration, especially by black men, of the hideous crime of rape” (Taylor 2019). An editorial in the Memphis Avalanche Appeal advised, “Let nigger keep his hands-off white women and lynching will soon die out.” And “[i]f it requires lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from ravening, drunken human beasts,” white women’s rights activist Rebecca Felton wrote in the Atlanta Journal in 1898, “then I say lynch a thousand a week if necessary.” In addition, consider the following excerpt from The Memphis Evening Scimitar published in 1892:

Aside from the violation of white women by Negroes, which is the outcropping of a bestial perversion of instinct, the chief cause of trouble between the races in the South is the Negro’s lack of manners. In the state of slavery he learned politeness from association with white people who took pains to teach him. Since the emancipation came and the tie of mutual interest and regard between master and servant was broken, the Negro has drifted away into a state which is neither freedom nor bondage.… In consequence … there are many negroes who use every opportunity to make themselves offensive, particularly when they think it can be done with impunity…. We have had too many instances right here in Memphis to doubt this, and our experience is not exceptional. The white people won’t stand this sort of thing, and … the response will be prompt and effectual. (Lartey & Morris, 2018)

It is important to note that these lynchings were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes; instead, they were targeted racial violence perpetrated to uphold an unjust social order. Any efforts to pass federal anti-lynching legislation repeatedly failed, largely due to concerted opposition by Southern elected officials. Due to this federal inaction and local indifference, only 1 percent of lynchings committed after 1900 led to a criminal conviction (Taylor 2019). In short, lynchings were terrorism that left in its wake thousands of dead African Americans and exponentially more politically, financially, and socially traumatized people. For blacks were not the only victims, as white people who witnessed, participated in, and socialized their children in a culture that tolerated the gruesomeness of lynching’s were also psychologically damaged. State officials’ tolerance of lynching created enduring national and institutional wounds (Lartey & Morris 2018).

The collapse of Reconstruction and the ensuing “lynching era” were not the only factors leading to an escalation of post-civil war violence against African Americans. Another factor that simply drips of irony was the adoption of the 13th amendment itself. Although the amendment was designed to abolish slavery it ultimately ended up providing slavery with a second lease on life. The problem with the amendment was not its primary clause decreeing an end to slavery but, rather, its subsequent clause stating “except as punishment for crime.” It was this caveat which left the door open for those who wanted slavery to continue, but in a new form. For it wasn’t long before a system was devised to arrest African Americans en masse, and thus was born the concept of convict leasing.

Convict leasing was a system that emerged in the aftermath of slavery, in which black people were subjected to a discriminatory set of “Black Code” laws which allowed African Americans to be convicted and sentenced for very flimsy and trivial offenses and then, as prisoners, leased as free labor to private businesses (Taylor 2109). Essentially, convicts became the property of the business owner who could subject them to intolerable or inhumane labor conditions and treatment. This frequently meant working 18-hour work days, seven days a week, often in deadly and/or toxic environments for state and private profit. Simultaneously, mainstream media and major newspaper outlets began lampooning blacks as inherently criminal, depicting them as dangerous, leading to ridiculously swift convictions before “bought and paid for” judges who then handed down a variety of lengthy or vaguely open-ended sentences.

As a result, it wasn’t uncommon for African American convicts to serve the rest of their lives in prison for menial offenses, such as not knowing “exactly” where they were while walking the street, i.e., loitering. Sadly, this system became a way for African Americans to be re-acquired by the very slave owners from whom they had been previously set free. As such, the most unfortunate irony is that the amendment crafted specifically to facilitate freedom for ex-slaves ultimately paved the way for the wholesale re-capture of African Americans into a new form of judicially empowered slavery. It was this tilted judicial landscape which, combined with continued support for white supremacy and laws written to target African Americans, created a new kind of modern slavery that some scholars described as “worse than slavery,” ensuring that slavery in America did not end with the Civil War — it simply evolved.

Part 4 posts tomorrow