This post is part of a series that originated out of a photo essay assignment in Dr. Simmons’s Interim “Religion and Pop Culture” course that asked students to apply discussion themes to everyday objects or experiences.

I think there’s a power in not caring about the opinions of others. If we place enough value on something, then no matter what the opinions of others are, we can still look at it with a sense of pride. Taking away the “unfortunate interruption of opinions” allows for someone to unironically love something (Kavanagh, 306). There are a lot of things we hold dear to ourselves that, in theory, have no “real” value on our lives. Of course, a lot of people would defend their family, friends, careers—but favorite music? Why do we place such importance on who our favorite artists are? Why do we get so defensive when others try and shut down our top picks? Why do we feel a little embarrassed sometimes if the person or group we’re into isn’t “real music”?

I’m going to go out on a crazy limb while writing this in order to defend my favorite musicians, and even as I write this, there is that little bit of embarrassment in admitting it’s still One Direction. My favorite boy band from middle school still holds a special place in my heart. Maybe it’s the power we place on nostalgia, or maybe the albums were just that good, but I still find myself coming back to play their music on every road trip or day with my friends. For most people (I’ve especially noticed for anyone over 35), this would be offensive to all the “real artists” out there. Where was the passion and heart and soul that should be poured into the lyrics? How could anyone put them above a “real” group like the Beatles or Metallica (real quote from my mother), who wrote important things and played real instruments? Now personally, I was born in 1997, making me the perfect age and demographic for One Direction when they came out. Their music grew on me in 2012, and nearly seven years later, I still appreciate it. Maybe for the nostalgia, maybe for the actual talent in the songs. Who knows? Honestly, who cares?

It almost became a thing when I was in middle school/ early high school to be “different” just for the sake of being different. Maybe it was just my school, but the phases of “I’m not like other girls” and “oh, I only listen to real music” were worn almost like a badge of honor. You wanted to be different than the girls who listened to “dumb boy bands” and more like the “cool girls” who pretended to care about Metallica. I, personally, never found myself a part of that. My friends and I waited eagerly for new music, new interviews, and sat around lunch and took those teen quizzes in the magazine that told you which One Direction member was your soulmate (mine’s still Harry, obviously). It was a fun bonding experience for us—we sang and danced to their albums, dreamed of going to their concerts, and taped pictures ripped straight from those same magazines to our lockers. To us, this was “real music.” It was straightforward and simple (and definitely written by a studio exec), but it was such a defining part of my middle school experience. Most importantly, it was fun and easy in a time that was anything but. I’ve never met anyone who said that they peaked in middle school, and for most, it was a complicated mess of emotions and daily drama mixed with the horrors of 2000s fashion.

People should be passionate about their favorite things. Life’s more fun that way, in my opinion. Place a value on your favorite artists, sports teams or TV shows. It shows a certain level of power to be completely unabashed in how you live your life. Look, I have no shame in placing the label of “real music” on pop artists, especially boy bands. Their music meant something to me and my friends, even if it didn’t have any real, life-altering results. Music like One Direction grew with me, through middle school, high school, and even college. Road trips with friends, getting ready for prom, even a first date all seem to have one of their songs in the background. I made an emotional connection with their music and that has value to me. I think importance is more than just technical—it also relates to how relevant and popular something is. It relates to how we feel about something and the personal connections created by popular culture, “an elusive term” (Fiske, 322). “Pop” isn’t a dirty word—it just means “what appeals to the most people,” and when did that become a bad thing (Fiske, 322)?

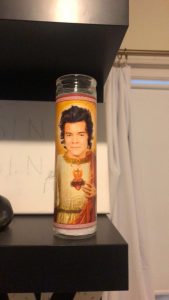

I love how people show their love for something. Shirts, posters, or literally anything that represents or depicts what you love can become incredibly “valuable.” I bought this candle for about thirteen dollars after a particularly good party. It was ridiculous and impulsive and taught me that it’s a dangerous thing to let your computer save your credit card information. But, I’ve had it on display in my room since I bought it freshman year, and it’ll most likely stay on a shelf until it breaks (or someone forces me to throw it away). I thought it was hilarious, but it’s also attached to good memories.

I like hearing about the importance of music in people’s lives. I’ve always enjoyed the stories my parents told me about seeing their favorite bands when they were younger, and I’ve loved making those same good memories with my friends over the years. Since the band broke up, I went with a friend to see Harry Styles over the summer. It was probably the best concert I have been to, and the memories and feelings attached to it mean a lot to me. It mattered then and it still continues to matter to me now. Maybe the Beatles were that for someone, or Metallica, or some band that you “got into wayyy before they were cool.” And it’s great that we as individuals are able to forge connections through music. Maybe music becomes “real” when it hits a certain level of skill—when the writing is like poetry and tells a beautiful, elaborate story. Or maybe it becomes “real” simply when people care about it. My interpretation and connections to the same song are going to be different than that of someone else, or even the artist themselves. We can look at why it’s made and for whom—“the translation for an audience” in order to take something away from an album (Mailloux 121). Whether music is “real” and “fake” depends on the person talking about it. Either way, it’s fun. And life’s short. Enjoy that cheesy pop song.

*Morgan Cavallaro is a junior majoring in History.