Matthew McCullough, an MA student in Prof. Ramey’s REL501 course, teases out the stakes of classifying an act as a tradition. This post originally appeared on the REL 501 Religious Studies & Social Theory: Foundations course blog.

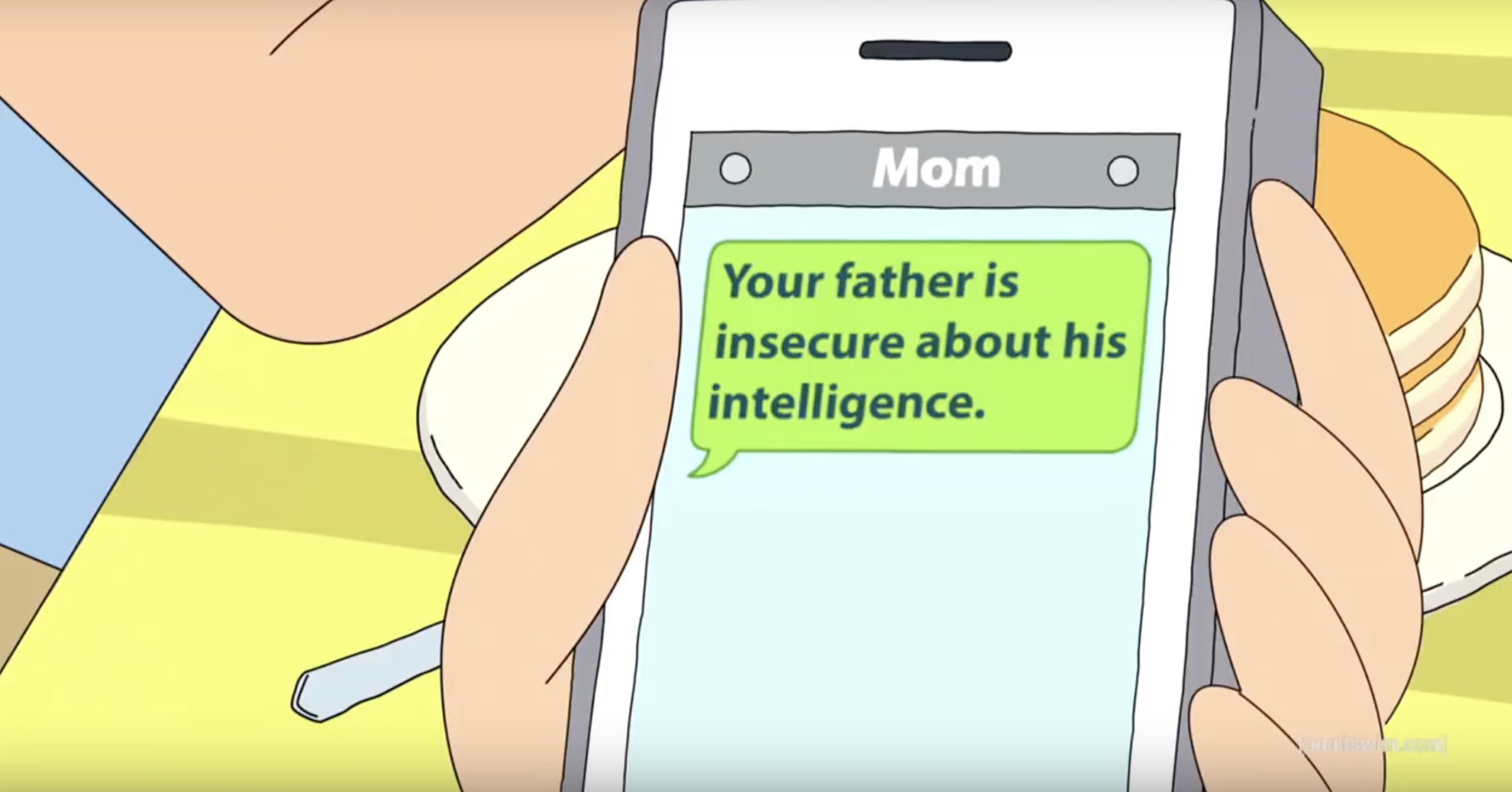

So, are traditions really an “idiot thing,” as Rick declares? Not quite. As we’ve seen in the clip above, tradition, appearing in various forms, is a device that’s used when something is at stake. There is no real tradition of science projects being done by fathers and sons. Projects are just as likely to be completed individually, with one’s mother, with a group, etc. What is important to note is that Jerry uses the language of tradition here because something is at stake. Jerry is insecure not only about his intelligence but about his relationship with his son Morty. He feels his father-in-law Rick overshadows him in terms of influence on and respect from his son, and Jerry worries that this science project is just another occasion when he will be subordinated to Rick. Rather than having to state this incredibly uncomfortable reality, Jerry instead uses the language of tradition as a basis to argue for what he wants. This turn shifts the issue from violation of his ego to the violation of a tradition, a longstanding practice that therefore merits repeating.

Calling something a tradition roots it in the past and manufactures a sense of authority for the practice in question by presenting it as time-honored and revered. The idea of something as a longstanding “tradition” suggests that it has been repeated numerous times over the years and therefore must be worth doing. This allows practices to be defended purely in terms of their being old, rather than on the basis of the utility they provide for an interested party. Back to our earlier example, the language of tradition hides Jerry’s interest in getting Morty to do the science project with him and instead suggests that doing otherwise would be breaking a longstanding (and therefore legitimate) pattern that should remain intact. In this case Jerry is inventing a pattern that doesn’t actually exist, but this doesn’t matter. Calling it a tradition implies this history whether it exists or not, and then shifts the burden over to Morty who would have to endeavor to prove that there is no such history, a difficult task in itself that also further distances argument from the practice’s utility for the interested party.

But it is not just invented traditions that should be subject to this scrutiny. Just because a practice has legitimately been repeated over a number of years does not mean tradition’s rhetorical effect is absent. Again, calling something a tradition creates an authority for the practice based on its repetition. This hides the interest of those benefitting from its continuation. Often those benefitting are members of the dominant social group. The language of tradition is an incredibly effective tool for conservatives and those seeking to maintain the status quo. Appealing to tradition is almost exclusively a call to continue doing things a certain way. Powerful people or groups can utilize the language of tradition in order to advocate for the maintenance of practices that reproduce the current social order from which they are benefitting, further cementing their position(s) of authority.

So what traditions do you see in your daily life, and more importantly, who might be benefitting from continuing them? Are they as benign as Jerry’s appeal to Morty, or could they have much more serious consequences for the way our society is structured?