A graduate of the department recently highlighted an intriguing Washington Post blog discussing the turmoil in Iraq. Avoiding the simplistic notions of blame (the Bush administration’s invasion or the Obama administration’s withdrawal of troops) that often depend on one’s own ideological perspective, the post develops a more nuanced historical narrative. Like typical historical narrators, the authors clearly promote a critique of US foreign policy that has clear ideological underpinnings, despite this nuance. They describe the “real culprit” as

A graduate of the department recently highlighted an intriguing Washington Post blog discussing the turmoil in Iraq. Avoiding the simplistic notions of blame (the Bush administration’s invasion or the Obama administration’s withdrawal of troops) that often depend on one’s own ideological perspective, the post develops a more nuanced historical narrative. Like typical historical narrators, the authors clearly promote a critique of US foreign policy that has clear ideological underpinnings, despite this nuance. They describe the “real culprit” as

the pure and undiluted self-interest of long-standing U.S. policy toward the country, and the contempt for the right of Iraqis to live in their own country with dignity.

Their narrative extends from the 1980’s US support for Saddam Hussein to events in the past few years within Iraq to illustrate how US foreign policy, serving to promote narrow conceptions of our national interest, has contributed to the current unrest.

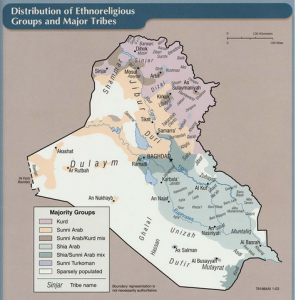

What particularly intrigued me in their narrative was the discussion (as you might guess from my title) of sectarianism. US policy-makers often viewed Iraqis as primarily sectarian, assuming that the allegiance of Iraqis lies foremost with Shia, Sunni or Kurdish communities. Of course, sectarianism is not something that the US generated out of nothing. Such identifications as Shia or Sunni pre-existed US involvement, yet the assumption of sectarianism encouraged a narrow view of the complexity of Iraqi politics and influenced US policy in ways that reinforced those identifications and distributed power, in some contexts, according to these identifications. For example, the authors argue,

The political system that it [the United States] designed and installed in Iraq was based on the understanding that Iraqis are sects and no more. It institutionalized sectarianism, injected it with political power, and made it the only political currency.

The authors also demonstrate that assumptions of sectarianism informed the analysis of figures like Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. When Maliki worked to disarm the Mehdi army, Moqtada al-Sadr’s milita, US officials used that as a demonstration of Maliki’s non-sectarian credentials, since he and the militia are both Shia. This declaration ignores how Maliki could have been using US support to remove a potentially strong opponent, whatever his sectarian identification.

But, then, who is this “we” that fostered this one-dimensional representation of Iraqis? While the Washington Post blog focused on the US government’s role, my use of “we” here extends beyond implicating myself, as a US citizen, with the actions of the US government. “We” are also scholars of religion who, despite nuanced research to the contrary, often represent others as primarily or exclusively motivated by their identification with religious or sectarian communities. In typical representations of those identified as Muslim, whether one promotes a negative image of inherent violence or a positive representation of peace-loving devotion, the end result becomes a narrow image that presents “them” as singularly focused on their identification as Muslims. Such an over-emphasis on interests and practices that we commonly label religious fosters the myopic account of Iraqis being purely sectarian. We easily recognize multiple and conflicting motivations in ourselves and others in our society but often draw other societies in a narrower fashion, ultimately dehumanizing them as simple communities whose sectarian identifications are always paramount.

Language such as this, that scholars often use to represent others, especially in generalized discussions, overemphasizes particular motivations and sectarian identifications that reinforce problematic assumptions and encouraged “the dysfunctional and sectarian political system the United States created in Iraq.”

Image credit: Ethno-religious map of Iraq from 2003, produced by the CIA, Public Domain