By Brooke Champagne

Brooke Champagne is an instructor of English and the Assistant Director of First-Year Writing at The University of Alabama. She received her Master of Fine Arts degree in creative nonfiction from Louisiana State University. While she makes her living as a teacher, she is a perennial student of writing, religion, and language, including REL 419 in Spring 2014.

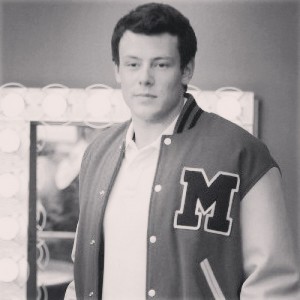

On July 13, 2013, 31-year-old Glee star Cory Monteith died of a heroin and alcohol overdose. He was found alone in the Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel in Vancouver accompanied only by two empty bottles of champagne, a spoon, and a used hypodermic needle. That harrowing final image does not comport with the one we see above: a strong, confident quarterback in his prime. Any minute he could drop back for a pass, or, knowing Glee, break into song.

Scandalous narcotic-fueled celebrity deaths aren’t surprising—sometimes they’re even prescient (Amy Winehouse told us from the start that she would not go to rehab). But Monteith’s death may have been more jarring for his millions of fans because of the role of the innocent that made him famous: Finn Hudson, the quarterback and hero of the Glee club. He was the talented, popular guy who didn’t need to be nice to dorks, but whose spirit demanded inclusivity. This Finn role shifted the old “quarterback” paradigm, previously known in the 1980s John Hughes oeuvre for being a cocksure champ, into a fresh 21st century version: a vulnerable, sensitive young man, a lost artist who is also a winner. The death of the actor, and subsequently, the character, further shifted that archetype. Heroes could have fatal weaknesses, and could succumb to them.

When Glee aired its Cory/Finn tribute episode, “The Quarterback,” the blogosphere balked at the title. A common question: “Wasn’t his character so much more than just a football player?” But the moniker is of course meant as a metaphor: this character was the club’s leader, the brightest constellation around which all others orbited. My issue with the title, and with archetypes in general, is that they ask us to create inherently rigid categories, and we are confused when certain figures don’t fit securely into the places we’ve made for them. This is further complicated on shows like Glee in which the character (Finn) and the actor (Cory) share similar traits (as written by the creators), but are ultimately very different people. With this we have an even greater multiplicity of archetypes working within one man. A quarterback, a lover…and an orphan, and an addict? The nuances were always within, but we were too busy cathecting to the archetypal trait of our choice to notice (likely the one that makes us most comfortable): the quarterback, the hero.

Photo by Sebástian Freire via Flickr under Creative Commons License, some rights reserved.