Manners constitute a restraint.[1]

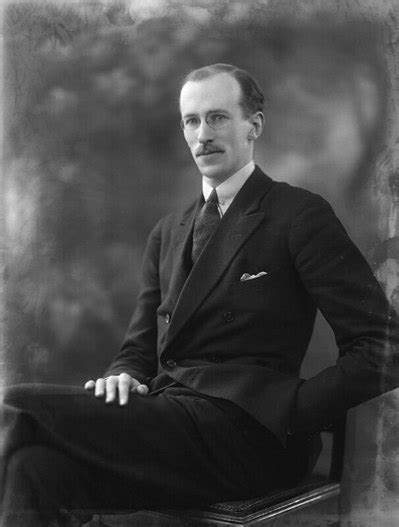

So quoth Basil Henry Liddell Hart, the British defense intellectual, writing in 1946. Liddell-Hart’s prominence among British policymakers and defense planners of his generation is difficult to overstate. Along with JFC ‘Boney’ Fuller, he was one of the first to understand the significance of the tank, and of mechanized warfare (though he was – or so the story goes – unable to convince the Exchequer to pay for them). Later, he would serve as defence/military affairs editor of the Times of London, and as a behind-the-scenes adviser to Secretary of War Leslie Hore-Belisha, until the latter was outmaneuvered and sacked. He even wrote a short infantry-training manual for the British Army (some of which appeared in reprint here).

This moment was one in which British ‘topsiders’ were confronting what to them seemed a profoundly upended world. The war was over, but victory had not come. Cracks and fissures began to appear from every side: everything, everywhere, all at once. The reality of nuclear war; long-deferred promises as regards India’s independence; imperial/commonwealth reform; simmering or open civil wars in Palestine and Greece, and murmurs of one in Malaya; disagreements with the Americans; a currency crisis; a vast extension of the British welfare state; Western Europe’s first steps toward unification – all challenged a new Labour-led government under Clement Attlee. Most diplomatic, imperial-military, and political elites had only the barest sense of how rapidly the empire would ultimately come apart; or how little it would be mourned by anyone save themselves.

This was, then, a time of particular uncertainty; a certain anticipatory anxiety. Wile E. Coyote can no longer feel the ground – but he hasn’t quite started falling. Not yet. Some of us might recognize a kindred form of anxiety at work in contemporary US politics.

Anxiety has an existential-theological component that may not be immediately obvious. The world seems to be coming undone. “Time is out of joint.” “The falcon cannot hear the falconer.” For believers of a certain strand (think of Kierkegaard), that feeling is thus both exceptionally potent, and exceptionally problematic. To put the matter rather too bluntly: to fear that the world is coming apart is to allow for the possibility that God has abandoned us. Think of those for whom climate change is not just frightening, but heretical.

Here, after all, is a political elite that had grown used to thinking of itself as the center of the world; as the bearers of a particular kind of political genius; even – in some circles – the Lord’s own chosen. To be sure, the crisis at Dunkirk, and the wartime bombing of British cities, had been terrifying; there was the fear that the island itself might be invaded, that London would have to be defended block by block and street by street.

But in another sense, the ‘Britain alone’ discourse – however contrived – confirmed a deeper sense of historical mission. They had stood where others had fallen. “Never…was so much owed by so many to so few.” Thus the saintly tincture to films like Dunkirk, The King’s Speech – or Gary Oldman’s iconic (in the religious sense) portrayal of Winston Churchill in The Darkest Hour.

The collapse of the empire is terrifying in a different sense. Perhaps we simply don’t matter all that much, after all?

Those accustomed to speaking of the US as ‘the irreplaceable nation,’ or the guarantor of a global rules-based order, might wish to take note: such self-congratulation veers rather close to hubris – or to nostalgia. “Those who believe they know where God’s favor is to be found,” noted Rowan Williams – scholar and devotional poet, and the former Archbishop of Canterbury – are “those most deeply in the dark.”[2]

As Williams – but also Cornel West, Catherine Keller, William E. Connolly, Jane Bennett, Shaul Magid, Elisabeth Anker, Wendy Brown, Elizabeth Samet, Behar Rumelili, Jennifer Mitzen, and a host of others – remind us, such anxieties link national security to the emotional and spiritual life of lived religion. Writing in 1950, the diplomatic historian and Christian realist Herbert Butterfield tried to reconcile these tensions thus:

“The world…trembles as though confronted with the specter of bankruptcy if the intellectual framework shows signs of breaking down as a result of its own defects. Precisely because he can hold fast to spiritual truths—not turning any mundane program or temporal ideal into the absolute of absolutes—the Christian has it in his power to be more flexible in respect of all subordinate matters, and to ally himself with whatever may be the best for the world at a given moment….It is open to him to unload himself of all the intervening years and event to cut through the traditions of historical Christianity, so that all may be fluid and flexible save for that ultimate rock, which is Christ Himself.” [3]

For Butterfield – a devout Methodist and a lifelong student of power politics – this is almost a counsel of despair. We cannot control the happenings of this world; nor even our own traditions – only Christ endures. Non nobis, Domine.[4] One sees similar tensions and ambivalences in similar statements by some contemporary American elites – one reason why I find this moment so compelling – and another variant of it in the UK’s ‘Brexit’ discourse. It’s close to a certain kind of tragedy – the classical, Sophoclean kind. A very different template for faith.

Liddell Hart was concerned about such matters too – though his solution draws on a different, more stoic, register. One must cultivate new outward manners, so as to control one’s fear: ‘keep calm and carry on’, ‘embrace the suck.’ A kind of ‘muscle memory’, but for the soul. Outward appearances point the way to resolving inner crises. (A similar wager can be found in the doctrine of the Haganah – the Jewish militia in pre-independence Palestine – albeit in a very different idiom; but that will have to be another post). The Lord helps those who help themselves.

This is more common than many of us realize. Think of the catechism (or Dune’s Litany against Fear): only instead of words effecting/sustaining a transformation in the soul of the initiate, it’s something closer to a set of bodily dispositions and appearances. To that end, Liddell Hart thinks women should return to wearing corsets – those old-fashioned support garments (once made of whalebones!) meant to force the body into a particular ‘hourglass’ form. Corsets, on his account, function like suits of armor – pointed inward. Yoke the body, and the spirit will follow. Mens sana in corpore sano.[5]

Liddell Hart’s comments appeared not in the pages not of The Times or the Journal of the Royal United Services Institution – his more familiar literary ‘haunts’ – but in an article about fashion. Why?

In part, because he was “on the outs” politically. He’d been involved in scandal, had an emotional breakdown, and his political patrons were in the political wilderness. But in part because clothes had become ‘securitized’ – ie, strategically significant – objects. “The apparel oft proclaims the man” – and men (or so, for better or worse, it was said) were the ‘stuff’ from which soldiers were made.

Except men (mostly) don’t wear corsets. If one detects a certain bait-and-switch of hand here – well, not for nothing. Lacking any way to impose his views on the public, biographer Alex Danchev notes, Basil turned his attention homeward. He instructed his wife and two stepdaughters to start wearing them, as part of a ‘crash course’ to recover a certain traditional English femininity. They were to dress for dinner; to cook and bottle their own jams and jellies; and to be “charming and witty” (a la Jane Austen or Bridgerton) when guests came round.

Whatever their shortcomings, we can at least say that Basil came by these beliefs honestly. It turns out, Danchev tells us, that he himself had worn a corset from time to time – a fact he was careful to keep private. Even so, that this labor of ‘restraint-making’ gets projected onto the women with whom he shared his private life is telling. It bears remembering that British women (in the home islands – not the empire) had won universal suffrage less than two decades earlier.

I came across Liddell Hart’s material while writing the introduction to a roundtable for a book written by a colleague and friend – Brent Steele, at the University of Utah – on emotional restraint and its role in world politics – while, at the same time, reviewing Liddell Hart’s archived papers last May.

Steele’s concerns, like Liddell Hart’s, come at a time of ‘late imperial anxiety’ – this time our own. He asks: what sensibilities and affects must we cultivate if we are not to break down into our own paroxysms of panic, overreaction, and violence? Do we not see a way in which our domestic political discourse has become overloaded with notions of panic, emergency, and catastrophe – but in ways that actually make productively addressing the causes of that anxiety harder, rather than easier? Do we not find ourselves ‘externalizing’ that anxiety onto the historically marginal – at home or abroad – whether parsed through discourses of gender, race, or ethnicity? How are we to understand these turns in our politics? What are we to do about them?

To be sure, Steele will have none of the spuriously ‘definitive’ solutions that Liddell Hart tried (successfully or not) to impose on the women in whose lives he shared. Though he clearly has views on such matters – views that echo of stoicism, the sociology of Norbert Elias, and the psychological writings of Carl Jung – that is not Restraint’s primary aim. Steele wishes to help us better understand the push-and-pull of anxiety and restraint in broad, descriptive-theoretical terms. Only then can we presume to address it.

If you want a longer ‘take’ on Steele’s Restraint, and a sense of how it’s being received/read, check out the roundtable here: https://issforum.org/roundtables/13-12

If you want to take a crack at the book, here are the details: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/restraint-in-international-politics/02C55BFBFF08BC11EE39D3240D54D280

Or if you have access to the University of Alabama Libraries, the e-book is available by using your UA login credentials: http://library.ua.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=8390102

Works cited:

[1] Basil Liddell Hart: “Manners Mould Mankind” (1946), cited in Alex Danchev: Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart (Wiedenfeld and Nicolson, 1998), 218. The best intellectual history of LH’s military theory remains Azar Gat’s Fascist and Liberal Visions of War (Oxford, 1998). Brian Bond’s Liddell Hart: A Study of his Military Thought (Rutgers, 1977) is a solid counterpoint both to Danchev and to Gat, as is – from another perspective – Beatrice Heuser’s Nuclear Mentalities (Palgrave, 1998), ch. 2.

[2] Rowan Williams: The Tragic Imagination (Oxford, 2016), 120.

[3] Christianity, Diplomacy and War. (Abington-Cokely, 1953), 3.

[4] “Not to us, O Lord [but to Thy Name give the glory].” Psalm 115:1 as rendered by the Vulgate; widely/ecumenically known from a range of popular choral settings (like this one, by Robert Quilter).

[5] “A sound mind in a sound body.” But which comes first, the chicken or the egg?