Vincent D. Jennings graduated in May 2020 from the University of Alabama with a dual B.A. in Religious Studies and Psychology. In the Fall of 2019 he began an in-depth study on America’s history of racial violence as part an independent study course with REL’s Prof. Theodore Trost — which culminated in this four-part series.

In that land…, that land…, that land…, in that great BIG BEAUTIFUL land…

Lord you know I will fare better in that land….

Sitting on the first pew of the church as an eight-year-old I recall the words of this song vividly, as the congregation sang on Sunday mornings. As the son of a pastor I was practically born in the church sanctuary, so my memories are rich and vibrant from those early years. I recall how the congregation would rock and sway as voices would bellow the words of this song, particularly the lyrics: “great BIG BEAUTIFUL land.” I remember being proud that I knew all the words as I sang along with the adults. It mattered very little that I didn’t fully understand the lyrics. The only thing that mattered was the shared sense of harmony permeating the room that seemed to transcend music.

At the mere age of eight, I was too young to wonder about the origin or meaning of the lyrics, or to ask such relevant questions as What are we singing about? Why are we singing about land? What is wrong with this land? And how do WE KNOW we will fare better over there? At eight years of age I really didn’t care about any of that; I just knew that I enjoyed the camaraderie unique to congregational gospel music. Somehow what I did understand, however, is that the music was not just mesmerizing but also messaging, even if I didn’t fully grasp its message. It wasn’t until later in life that my curiosity required a deeper understanding of those church songs from my youth.

So why were we singing about, of all things, land? And what was it about that land? In my early adult years, it began to dawn on me that songs such as this were the heritage of my slave ancestry, with lyrics born in the souls of a people who were snatched from their own land, and forced to live and die on a land that was strange and nightmarish.

I later pondered how many generations of my ancestors died with a dream in their heart to one day inhabit a “great BIG BEAUTIFUL land” that would not only be familiar but also kind. As an eight-year-old I could never begin to fathom the historical or cultural implications rooted in the songs that I sang or how they would pique my research years later. This series of posts represents my coming of age from an 8-year-old who was unaware of even the most remote lyrical significance to an academic scholar ardently probing what motivated my ancestors to sing so about a “great BIG BEAUTIFUL land.”

America… America… God shed his grace on thee…

And crowned thy good with brotherhood,

from sea to shining sea.

This other song is intuitive to America’s mainstream, summoning music which intersects patriotism with this nation’s storied history. Yet there is a significant segment of American history that reflects poorly on both America’s good and its brotherhood. It is America’s legacy of racial violence, brutality, and murder against African Americans. This part of American history is frequently glossed over, met with polite cursory acknowledgement, or preferably tip-toed around. But rarely does mainstream academia, legislators, or cultural historians demonstrate an appetite to thoroughly examine and discuss the facts associated with this legacy of atrocity. Although downplayed frequently, this country’s legacy of violence against African American’s has been every bit as defining to this nation’s legacy as the iconic stars and stripes: it is a legacy of such brutality and shame that, for most Americans, the best coping mechanism has been to not discuss it, ignore it and never glance its way, utterly convinced that if I do this long enough it will somehow disappear; however, lurking in the shadows for the last 400 years, there are still those who are singing, “I know I will fare better in that land.”

In 1776 the United States of America officially became a nation. In the relatively short span of 350 years since it has soared up the list of the world’s most racially divided and polarized nations. In 1997, when African American NFL hall of famer O. J. Simpson was acquitted of the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman (who were both Caucasian), a whopping 83% of white Americans were convinced he was guilty. Meanwhile, 70% of African Americans believed he was innocent (Rory 2017). The fact that the perspective of Americans could be so racially polarized was a wake-up call to the entire nation and crystallized what many had long denied: that we are a nation of two Americas. But how did we arrive here? How did we, the nation of “In God we trust,” end up so fundamentally and racially divided? Or, expressed another way: How did we become a nation where the heritage of one group inspires lyrics about this “sweet land of liberty” while the heritage of another awaits liberty in a “great BIG BEAUTIFUL land” afar? The answer is nestled in one of America’s most shameful chapters: its legacy of slavery and systemic violence against African Americans.

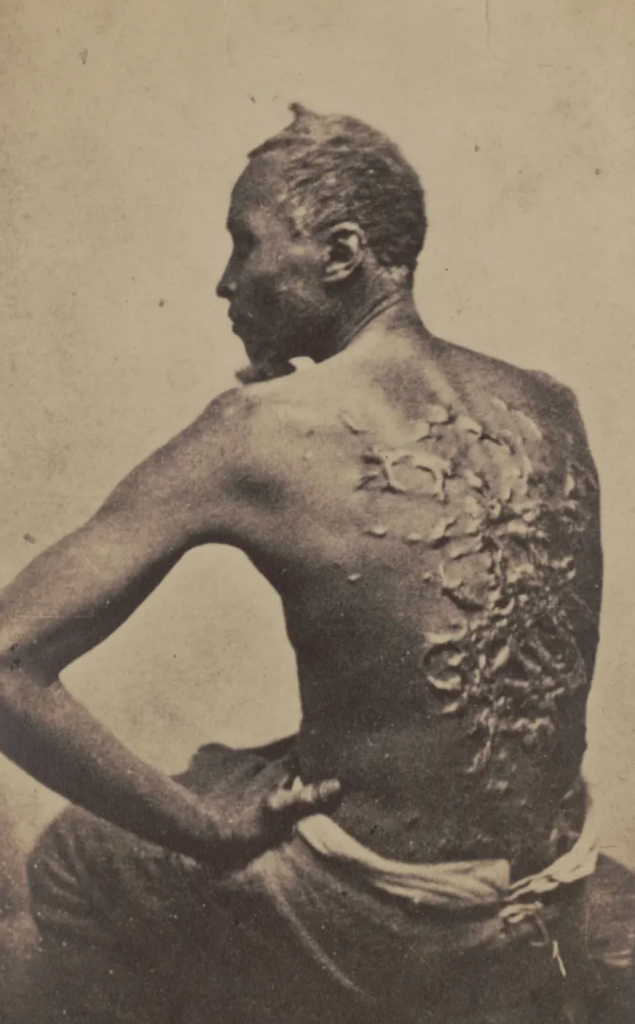

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 12 million Africans were kidnapped, chained, and brought to the Americas (Taylor 2019). White slave captors, upon landing in Africa, and throughout their subsequent journey back across the Atlantic, began to initiate a brutal and systemic level of violence against blacks, with implications that reverberate to this very day. Captured slaves were forcibly indoctrinated to the atrocities of rape, sodomy, dismemberment, castration, and murder during their trans-Atlantic journey, as their white captors dismissed such atrocities as requisite to establish a new social order. The process of dehumanizing Africans cauterized the sensibilities of their white captors to such an extent that by the time the first slave ship landed in America the appetite for violence against blacks had become inextricably hardwired. This set the stage for the violence and brutality perpetrated by whites against African Americans to not only become normalized but to escalate in the years to follow to horrific and sadistically unforeseen levels.

After arriving in America, the free labor rendered by slaves fueled tremendous economic growth; enslaved African Americans were the engine. In order to get mainstream America onboard with the unconscionable level of associated atrocity, including but not limited to tarring and feathering, skinning, burnings, castrations, and drownings, the ideology of racial differences and white supremacy was advanced to justify slavery as morally acceptable and to make its brutality more palatable. During the early and mid-1800s America’s burgeoning economy was based on plantation driven revenue and the forcible taking of land from the Native Americans. The South’s insatiable appetite for slave labor increased exponentially and, by extension, so did the South’s slave population and the intertwined level of violence against the slave class.

In 1865, after the defeat of the confederacy in a bitterly contentious Civil War (which primarily revolved around the issue of slavery), the nation adopted the Thirteenth Amendment to the constitution — an amendment which decreed an end to slavery. However, the ensuing years would prove reality to be neither that straightforward nor simple. For many white Americans, especially southerners, their identity was rooted in the premise of an inherent superiority to African Americans and, as such, they bristled at laws stipulating that they treat their former “human property” as equals and/or compensate them for their labor. Instead, their visceral response was an embittered escalation of violence and terror towards African Americans during the initial years following the Civil War. Violent and unprovoked mob attacks by whites on black communities in cities such as Memphis and New Orleans were two notable examples of a sweeping pattern of national violence against blacks.

Part 2 posts tomorrow