Christopher Hurt is an REL alum who works in tech in Los Angeles. He is best known for his work with the rock ‘n’ roll group, Jamestown Pagans.

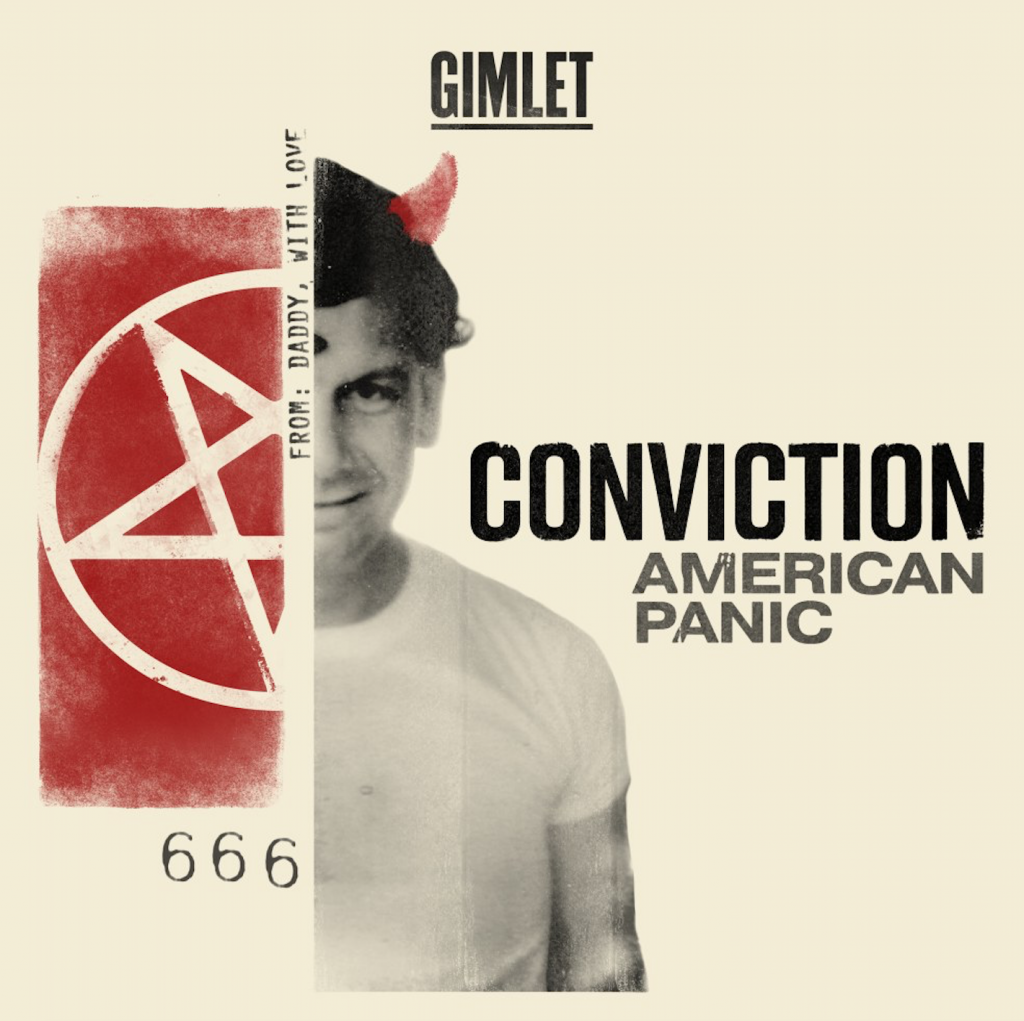

I recently finished listening to a podcast called Conviction. I listened to the second season specifically. It centers on families affected by the Satanic Panic and since I’ve written about this before, and it’s a big part of my academic interest, I felt compelled to compose another piece.

The thing I found most powerful about the podcast is how it materialized (made bump-into-able) the consequences of the time period. You see, there’s plenty of content out there for an Occult Rock band to slap into their Instagram feed (I’m thinking of VHS-quality snippets of police training videos, evangelical broadcasts, and primetime television specials.) Hell, even a recent book about the subject is subtitled Pop-cultural Paranoia in the 1980s. Sounds kind of fun, eh?

During the final episode one of the main characters, John Patrick, makes a comment that the naming of the phenomenon is sort of a disservice. For him, it’s more than just a panic. It made me think about something I read while studying religion at The University of Alabama. It’s called The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.

One could read Baudrillard’s essay collection as a criticism of narrative. In short, narratives tend to be linear. They go from one dot to the next in a straight line and have a clear ending point. They tidy up the mess of history. But as this podcast demonstrates (for me, at least), the Satanic Panic has implications (estrangement, criminal conviction, ineligibility for employment) that reach far beyond the mid 90s, and past the present day.

If we apply that idea to studying religion — that narratives tidy up the mess of history — how might it change the field?