Brady Duke is a senior at the University of Alabama majoring in Religious Studies and Latin. After graduation, he plans on pursuing a master’s degree in Classical philology with a concentration in Latin language and literature.

Throughout this semester, we have been learning various ways in which individuals, either scholars or laypersons, interact, define, and interpret the past. Consequently, the interpretations stemming from these discourses reflect more about those analyzing the object of study than the object of study itself; while it is quite the claim, everyone frames their object of study in such a way as to highlight their own interests, the degree to which these interests are explicit being the only difference. Thus, through these discourses, we are able to see the underlying interests at work.

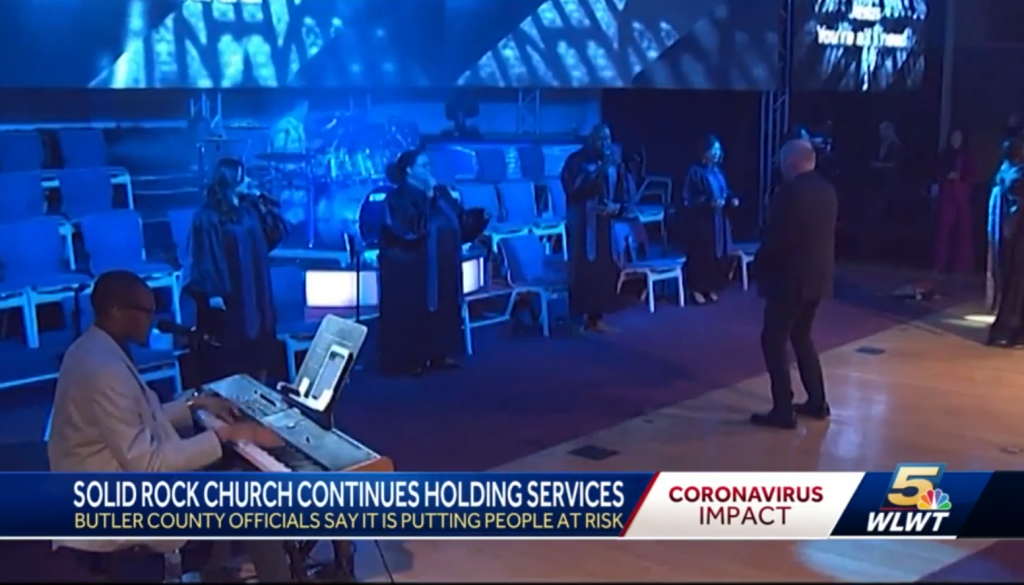

Such is also the case in “Ohio Megachurch Keeps Holding Mass Gatherings, Even as Coronavirus Spreads.”

To provide some background information, this article was published on March 26, 2020, on HuffPost, a left-leaning American news and opinion website and blog; Tom Perkins, a freelance journalist based in Detroit, Michigan, wrote the article. The overarching topic stems from the controversy surrounding the Solid Rock Church’s (a non-denominational megachurch in Lebanon, Ohio) decision to continue holding in-person services despite Governor Mike DeWine’s “Stay at Home” order. While DeWine structured provisions in his order that allowed religious institutions to continue to operate as usual per the First Amendment, Solid Rock continues to face public backlash for its decision.

The article shifts back and forth between each side of this issue: those for and against Solid Rock’s decision. (I will refer to those for Solid Rock’s decision as Group A and those against Solid Rock’s decision as Group B.) Group A claims that DeWine’s “Stay at Home” order does not apply to religious groups due to the First Amendment, specifically the clause which prevents the government from restricting an individual’s right to religious assembly. Group B claims in times of national emergency, such as during the COVID-19 global pandemic, government “Stay at Home” orders do not violate First Amendment rights, when it is in the public’s best interest. Interestingly enough, both Group A and B use the Constitution and the Christian faith to support their argument. This is the issue I wish to focus on: how the same item can be framed in different ways as to support one’s interests.

At its core, both sides to this issue are citing the First Amendment, but highlighting different clauses, in order to justify their thought process. Group A argues that it is important in this time to continue to hold in-person services. Despite the “Stay at Home” order, Group A claims:

The First Amendment of our Constitution guarantees freedom concerning religion, expression, and assembly…. It specifically forbids Congress from restricting an individual’s religious practices. Therefore, the government ban on large gatherings does not apply to religious worship.

On the obverse, Group B argues:

There simply aren’t blanket protections in the Constitution, and that’s why something like a ‘Church of Human Sacrifice’ won’t exist…. The question in the coronavirus crisis centers on the point at which a ‘compelling government interest’ overcomes religious freedom or right to assembly. We are likely at that point…, though some qualifications exist. The order must be applied generally to all large gatherings … and can’t permit nonessential businesses to remain open while requiring churches to close. The businesses that remain open must be critical government services, hospitals, grocery stores, and the like.

Ultimately, the interesting aspect surrounding these arguments centers around how both Group A and B frame the First Amendment in a way that helps their case. They take the same piece of text and develop narratives of the past which are relevant to their respective arguments. They are taking a piece of text written nearly 250 years ago and imposing modern interpretations of its message, which, at least in this case, blatantly reflect their interests. And, as irksome as it can be to admit, neither group’s interpretation is incorrect — but it is not correct either. Instead, their interpretations are incomplete. Both groups are including and excluding aspects of the First Amendment, Bill of Rights, and the Constitution, as they see fit. Why did neither Group A nor B cite the Second Amendment to support their argument? Or the Tenth Amendment? Because they deemed that it is not relevant to their argument. Overall, there do not appear to be significant differences between this discussion and discussion on the past; both rely on studying objects and determining their significance from an outsider’s perspective who attempts (most of the time anachronistically) to provide a description which they deem to be fact.

Not to make a political statement, but would each group’s argument remain the same if another religious organization was continuing to hold in-person services, such as a smaller Christian church, a mosque, or a temple? Would Group A continue to argue that these government restrictions violate the First Amendment now that the discourse no longer directly serves their own interests? Would Group B still oppose the decision? Would the same critiques be made during a particularly contagious flu season? By changing the context of the discourse, we begin to see the extent to which these discussions serve the interests of those involved. The issue becomes significantly more complex than potential violations of the First Amendment; it becomes a discussion of competing interpretations of the past and their consequences in the present. The meaning of the First Amendment is not inherent in the text itself; however, its meaning comes from the interpretations of individuals and the ways in which it is framed in a modern understanding. We see this in the Supreme Court, whose entire purpose is to provide modern interpretations of this ‘living document’ and insight into what the ‘ancient’ authors meant. Thus, each of these groups are acting as a quasi-Supreme Court, providing their own understandings of what they feel is the true meaning of the Constitution.

This case study shows that meaning is not inherent in the object of study but is a byproduct of the framing and interpretation done by those producing discourse, be they scholars or laypersons. It is by examining the ways in which objects are framed and interpreted that scholars are able to see how interests, or competing interests in this case, are at work. It is important to remember that no one interpretation is more correct or more authentic to the original meaning of a text or object of study, be it ancient or modern; the true meaning, if one even exists, is lost to us. Scholars must therefore remain realistic in their descriptions, not assuming their portrayals are a matter of fact but are creations themselves.