Martin Lund is senior lecturer in religion at Malmö University in Sweden. He is currently working on a co-authored book about the “supervillain” Magneto and a single-authored book about the “superhero” and theory.

For many of us, the world seems a pretty strange place right now. What we consider “normal” has been upset and we’re having to make adjustments. People are reacting in different ways, some enthusiastically embracing self-quarantine and others grousing that they can’t go about their business as they like. It’s probably pretty safe to say that whatever else, many of us are getting a bit squirrely in our houses and apartments.

For some people, however, there is no choice in the matter: some of us are encouraged to work at home as much as possible – for us in the university this generally means pivoting to online teaching and sharing bad jokes about Zoom, but others are considered “essential workers” (or some variation thereof) and have to keep going to work. “Essential workers” are classified by the Pan-American Health Organization (somewhat circularly) as “the personnel needed to maintain essential services”; “essential services” in turn are “the services and functions that are absolutely necessary, even during a pandemic” and include “executive governance, healthcare, fire and police protection, provision of clean water and basic sanitation, infrastructure and utilities maintenance, and food provision.”

So, “essential personnel” marks a category of people seen as necessary to keep our societies running in something like their shape before the pandemic hit. That’s not a small responsibility to bear, and it’s a categorization that has inspired disparate reactions from “essential workers’” neighbors, now that this necessity has been brought into the heart of public discourse. In some places, like Minnesota, workers in fields that have long been considered “starter jobs” and not worth more than minimum wage (if that) have been reconceived as doing “essential work.” For some, as a writer for the Financial Times notes, this whole situation has been a revelation. Economies around the world “are going into hibernation” and the fact that “essential workers” are keeping the lights on and people fed has “exposed an uncomfortable truth: the people we need the most are often the ones we value the least.”

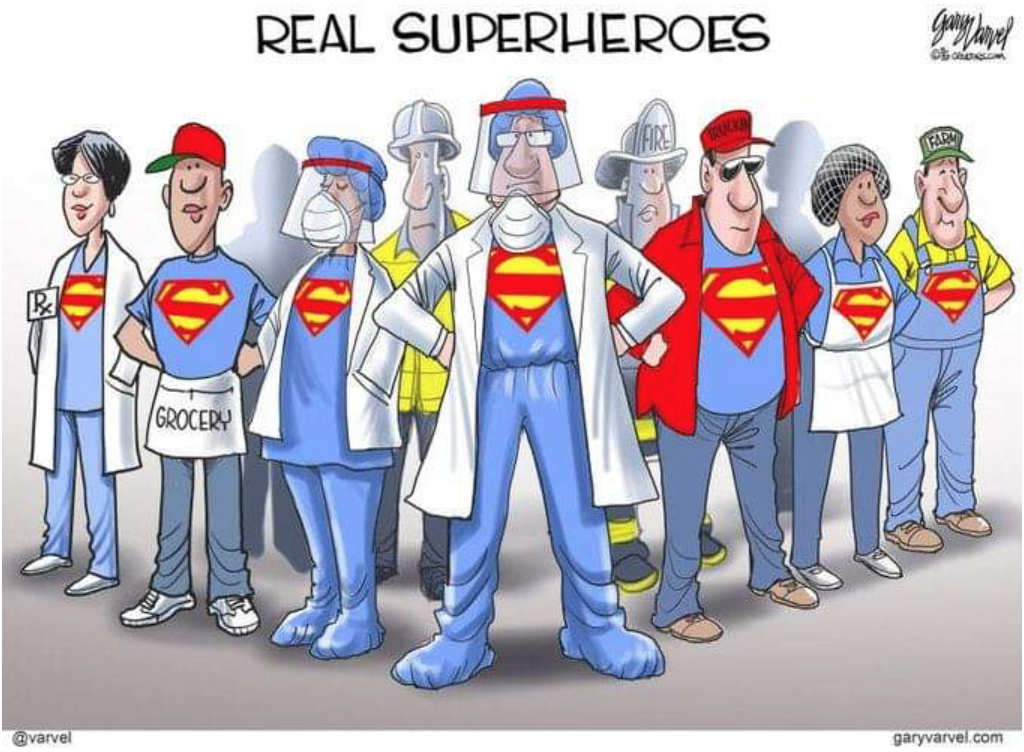

On the other hand, many have taken to mythologizing “essential workers,” placing them rhetorically above and outside the realm of the everyday, or even the human, by comparing them (albeit favorably) to “superheroes.” This is perhaps less surprising in the current moment than it has been since the so-called “superhero” figure first appeared on our cultural arena. After all, “superheroes” are big right now. Really big. But perhaps it points to something other than the zeitgeist: “superheroes” offer easy fixes, almost always completely divorced from structural factors and considerations, and stand largely above the fray of labor policy and worker protections.

I work with “superheroes” a lot in my research, so I consume a lot of “superhero” comics, movies, and TV. In my household we’re currently re-watching the CW show Flash and an episode from the other night can prove illustrative. A newly introduced character, Wally West (who will soon become the superhero Kid Flash), tells his policeman father that he wants to help people like the “superheroic” Flash – a desire he juxtaposes with designing cars as an engineer. The quick fix of fighting the “supervillain” du jour is juxtaposed against the “unhelpful” banality of, say, changing fuel economies, lowering emissions, or increasing car safety; things that can, and do, help save millions of lives and might even be able to affect the tide of man-made climate change.

While today’s rhetorical valorization of “essential workers” is going on, we are seeing that much of it seems to be just that, rhetoric in the pejorative sense: medical personnel are being told not to talk about equipment shortages that put them at increased risk as they do their essential work, on pain of firing; grocery workers, who never signed up for anything like the risk they have to take every day when they clock in, are hailed as heroes, but many still have to worry about making ends meet if they get sick, about having sufficient protections at work, and about customers not respecting social distancing guidelines; public transportation staff risk – and some have given – their lives getting people to places they might not strictly need to go, and that some travel to without adequate concern for their fellow passengers or drivers; and some workers at have taken to walking out in order to demand protections and benefits that rise to even the symbolic level afforded some of the aforementioned professions. Many of the changes implemented to safeguard the essential worker are temporary, and in many cases do not measure up to the needs of the moment.

This disconnect between rhetoric and reality, and the frequent recourse to “superheroes” in lieu of listening to the worries of the people we lionize, says something about what is valued in our current historical moment and social formation. And it suggests that, for many, professions that are in some ways crucial to maintaining a functioning society must be made into something else, in this case imbued with a superhuman imprimatur, in order to be appreciated in public discourse. Cheering people on, calling them something nice costs nothing; putting the “S” on their chest, while intended as a nice gesture, removes from history and politics what is happening, the risks being taken, the human cost and sacrifice attached to what we take for granted as the everyday.

As commonly understood, “superheroes” do what they do because they want to help, and expect no reward but the satisfaction of helping. “With great power comes great responsibility,” a frequently cited version of Spider-Man’s guiding axiom tells us. If you can help, you must help. But in “superhero” stories the help comes to individuals from individuals, and the debt owed is seldom reciprocal. The “superhero” doesn’t need hazard pay, health coverage, or safe working environs. The “superhero” gladly runs into danger.

That “S” then, isn’t so much a signifier that we value what people are doing for us and the risks they put themselves in daily to make sure we’re fed, healthy, and entertained, nestled in warm, well-lit houses with access to (for many) clean water. It’s a way of saying we appreciate what they’re doing, to be certain, but also, in a sense, a way for us to disavow the need to consider that they need something from us too, right now – stay home, wash our hands, cough into our elbows, keep our distance, be quick in the store, etc. – but also tomorrow.

The two reactions outlined briefly above can be seen as stand-ins for a bigger question that will have to be considered before something like the status quo ante pandemic returns: how do we want to classify essential workers in the future? As Sarah O’Connor notes in her Financial Times article, “the pandemic has forced us to acknowledge problems we have long found it easier to ignore” – and, I hasten to add, which at some point we will be able to ignore again, if we so choose. Do we want “essential workers” to be paid a wage that measures up to the value of the work they do for us, and promote the structural change that doing so entails? Or do we want them to be superheroes, jumping in for the duration to provide a quick and easy fix and then fade from view until they’re needed again?