This post is part of a series that originated out of a photo essay assignment in Dr.Simmons’s Interim “Religion and Pop Culture” course that asked students to apply discussion themes to everyday objects or experiences.

This post is part of a series that originated out of a photo essay assignment in Dr.Simmons’s Interim “Religion and Pop Culture” course that asked students to apply discussion themes to everyday objects or experiences.

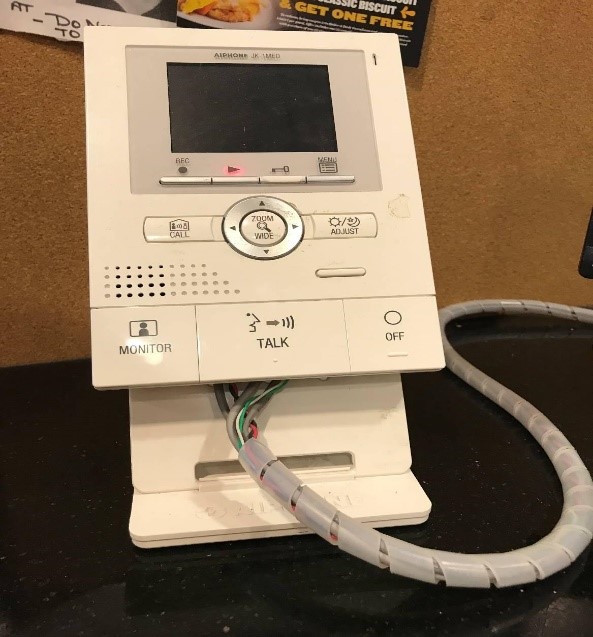

As I was sitting at work the other day at Bryant Denny Stadium, the doorbell buzzed turning on the camera to let me know someone was outside. Using the speaker, they explained to me why they were there. This is part of my job. People ring the doorbell, explain to me why they are there, and I decide if they get access to the building. A few weeks ago, the doorbell rang and as I was about to hit the unlock button, I realized that I recognized the person outside. One of my past professors was standing outside waiting for me to respond. This professor was…not my favorite, to put it diplomatically. For a few seconds, I sat there debating on if I should let him in. Here I was sitting at my desk, a student, but I had the power in this setting. This power was situational but absolute. Outside of that building, I have no power in comparison to the professor. In class, I had no power, but he did. At the moment before I open the door, however, I get to make the decision of who can enter and who cannot. I, a student worker, control the access for one of the most important buildings in Tuscaloosa. People come from all over the world to this building, but I get to make the decision if they get to come inside. This one instance made me think about the peculiarity of power. Who grants it, who has it, and who does not are all constantly changing. Whether or not we realize it, we can observe these shifts in our lives every day if we pay attention.

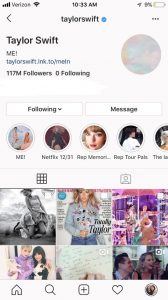

Most people use some type of social media. In these domains, we can connect with different people all over the world. When looking at some profiles on Instagram, you might notice a small blue checkmark beside the handle. A blue check mark means that they are “Instagram verified.” This checkmark serves to distinguish between real and fake, known and unknown, and popular and unpopular. There are a few ways to get verified. Instagram gives the symbol to public figures, celebrities, and authentic brand accounts, but within the past year, they have created a feature to allow users to apply for it. Instagram did not release their criteria for deciding who gets a checkmark, but when you have the blue check mark, you have power through influence. We perceive people and their content differently if they have this tiny symbol. For example, if Taylor Swift releases a new song, I am going to listen to the entire song and might even share it. However, if I see someone without the check mark post about their song, I might listen to half of it before scrolling past. If you have the blue check mark, you have the authority that comes with it. Whether it be a group of fans or a group of Instagram employees, the relevance of an account is determined by other people. This determined relevance then gives the user power. As John Fiske suggests in his discussion of popular culture, “Popular selection, then, is performed not by universal aesthetic criteria of quality, but by socially located criteria of relevance.” Power is a precarious thing that we must always actively maintain by staying “relevant” to others.

We can also observe the unsteadiness of power in sports. Imagine a baseball player missing the ball during the last play of a game, throwing it past another player and letting the other team score and win the game. Obviously, losing the entire game was not that player’s fault, but many fans blame that one play. Fan collectives make choices about prestige and power. When a player is doing well, the players are praised and celebrated as heroes. Athletes must constantly perform at a high level in order to maintain their power. We do not blame the player who got out two pitches before or the one that held onto the ball a little too long and let the other team score in the first inning. We blame the player that we decided made the worst play because of its timing. Until someone messes up, we see the entire team as one powerful group. If someone makes a mistake in this group, they are removed from that imagined power. Fiske explains, “popular discrimination does not stop at the selection of the commodity or text, it then selects the functional elements within.” People decide not only who has power but also who does not. Because power dynamics are precarious and always-changing, those who have it must work to keep it. We cast out and blame what would take that power away. Whether we have power because of a place, followers, or teams, the power we have is situational and contextual. If we do not perform our power successfully for others, it will break down.

*Olivia Smith is a pre-med major.