Jackson Foster is a freshman at UA, majoring in Religious Studies and History and minoring in the Blount Undergraduate Initiative and Randall Research Scholars Program. He is currently studying the intersections between law, politics, and religion in Dr. Altman’s REL130 course. This piece was originally published in High School SCOTUS, a national Supreme Court blog comprised of young students like Jackson.

Jackson Foster is a freshman at UA, majoring in Religious Studies and History and minoring in the Blount Undergraduate Initiative and Randall Research Scholars Program. He is currently studying the intersections between law, politics, and religion in Dr. Altman’s REL130 course. This piece was originally published in High School SCOTUS, a national Supreme Court blog comprised of young students like Jackson.

The Supreme Court heard arguments last month in American Legion v. American Humanist Association, a case involving a 40-foot Peace Cross situated in a Maryland public park. Before (and since) the argument, American Legion has received special attention from the constitutional scholar and layman alike. It has been enveloped in media scrutiny (see Nina Totenberg’s Cross Clash Could Change Rules For Separation Of Church And State); it is one of the first Establishment Clause cases in the Kavanaugh era, and it may spell the end of the Lemon test.

While constitutional considerations carry great weight, they miss the heart of this case. American Legion does not so much implicate the Establishment Clause or the Lemon test as it implicates American civil religion. The questions argued in the case, therefore, can be nicely distilled to one: Is the cross civil or sectarian?

Let’s first take a crash course on civil religion in America, as pioneered by sociologist Robert Bellah. From Bellah’s system, we get five main components: god talk; founders and documents; the book of Exodus; death, sacrifice, and rebirth; and the ritual calendar. These parts, in turn, form an “elaborate,” “well-institutionalized,” and “[non]-sectarian public religion.” But these parts — and by extension civil religion itself — are fluid, frequently changing in the direction of our nation’s socio-cultural evolutions.

The Peace Cross was created in 1918, a time when the Social Gospel movement had reached its apex. As a result, the Bellian ideal of an “implicit but quite clear division … between … civil religion and Christianity” was diminished. And although this diminution blurred the lines between the Christian god— its iconography, sacred texts, etc.— and its civil counterpart, the cross at issue here was created for a commemorative purpose, connecting to themes of “death [and] sacrifice” more than sectarian devotion.

Or at least that’s what Neal Katyal, who argued in favor of keeping the cross, seems to think. “Families and the Legion built it 93 years ago,” he said, “to commemorate 49 brave souls who gave their lives in World War I” (italics added). He re-phrased this more explicitly: “A group of people decided long ago that this cross was the most appropriate national symbol to honor the sacrifice of those who passed in WWI.” Thus, the cross was (and still is), as Bellah would say, “[an] express[ion] [of] what those who set the precedents felt was appropriate under the circumstances.”

But we know that pluralism haunts these traditionally non-establishment yet undeniably sectarian statues and figures like some “ghoul in a late-night horror movie.” (I know the prior quote is about the Lemon test, but, c’mon!— it’s too fun not to use Justice Scalia’s sardonic analogies.) In last month’s argument, Justice Kagan struck at the core of the ever-growing influence of pluralism on our civil conceptions. “What would happen if all the facts that you gave were the same, except for the 93 years?” she asked. What would happen, as she knows, is the city council would never approve such a gaudy cross or any cross at all. If they did so, it would undoubtedly be an Establishment issue. After all, “religious ethnocentrism declined significantly during the century,” meaning our religious displays must now include space for our nation’s 3.5 million Muslims, 20 million atheists, … etc. But Deputy Solicitor General Wall disagrees, arguing instead that the “nation’s long tradition of accommodating religious speech or symbols in civic life” overcomes the Peace Cross’s Establishment problem.

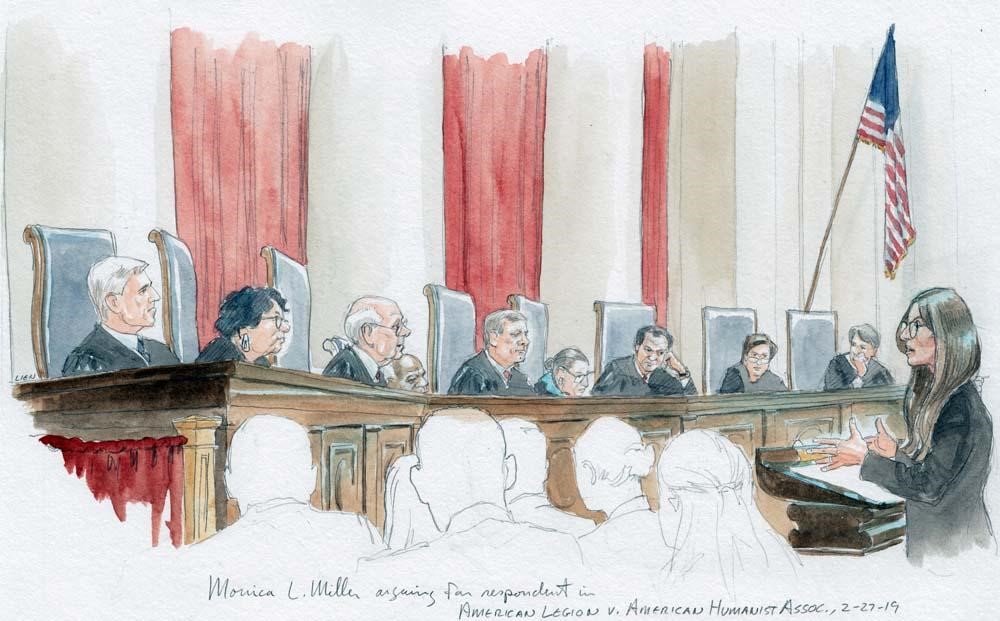

The cross’s commemorative purpose (or lack thereof) only further complicates the issue. To be secular, according to American Humanist Association’s lawyer Monica Miller, “the commemorative purpose” of the cross “would need to predominate over the sectarian.” Wall believes that the cross exists well within the classificatory system above: “It has taken on a secular meaning associated with sacrifice or … death or commemoration.” Justice Kagan, however, sees the cross “as a way [for Christians] to memorialize the dead…, because it connects to [Christians’] central theological belief … that Jesus Christ … died on the cross for humanity’s sins and that he rose from the dead.”

The cross is a Schrödinger’s cat of sorts, caught in a quantum state— being beyond a “sectarian meaning” (the words of C.J. Roberts) to some, mostly of a time gone by; and outright devotional to others, mostly of the here and now.

Alright, we get it. Establishment issues are difficult, a kaleidoscope of civic and sectarian shapes. So what? What’s next?

Let’s handle these questions for American Legion first, by reviewing some possible outcomes of the case:

1. A divided court rules that this cross is secular because of its age and commemorative purpose.

This outcome would comfort people who fear that the U.S. government is removing religion from the public sphere. But a decision like this means that the cross is nothing more than a secular figure, like a Christmas tree. And if “secularizing the cross” is as blasphemous as Justice Sotomayor contends it to be, then this victory is “a Pyrrhic one indeed” (see Justice Blackmun in Lynch v. Donnelly).

Additionally, this result would slow the court’s Establishment Clause caseload for the foreseeable future. American Legion is an archetypal establishment case: Different people from different times think a symbol has different meanings. If the court doesn’t rule favorably for the respondents here, you’d be hard pressed to find a case in which it would.

Finally, a decision for the American Legion might predicate a new constitutional standard for passive displays— erasing, at least in this one sphere, a great deal of the precedential weight of the Lemon test.

2. The court rules in favor of the American Humanist Association, exposing themselves and their lower-court colleagues to an inundation of Establishment cases.

This result is unlikely, with the new conservative tilt of the court contributing largely to this unlikeliness. However, a ruling for the Humanist Association would re-solidify the Lemon test as the standard par excellence for passive displays of religious iconography.

Of course, there could be punts, pluralities, and many more unexpected twists to this case— but these two outcomes seem to be the most plausible. The cross will either be seen as civil enough to stand or not; and from there, the court will need to pick up the jurisprudential pieces.