This morning I caught a tweet that struck me as just as curious as the responses from some on Twitter.

This morning I caught a tweet that struck me as just as curious as the responses from some on Twitter.

First off, the tweet:

A professor who received his PhD from Harvard was asked to give some advice to potential grad school applicants today: [paraphrased] “Um, the job market was good back then and it was super easy. I have no real insight into the current process. I’m sorry.”

— Shane Wagoner (@shanewag1) February 2, 2019

It’s curious to me because, unless the person in question earned their Ph.D. in the early 1960s, the job market in the Humanities has not been good for decades, though sure, due to even more declines in public support it continues to degrade in ways that make the market 30 years ago look “good” when compared to today. But, speaking from my own experience, it was not “super easy” to get a job when I first stepped onto the market (early 1990s) — either for myself or most of my peers at the time.

So, lesson #1 is easy to draw: beware how you generalize from your own experience.

For maybe this person had a specialty in an area that, at the time, was highly sought, such as some sub-fields/specialties in the study of religion even today, in which the demand is far greater than the number of people able to fill the open positions. But, for the most part, that’s rather anomalous, given that the number of positions in most areas is far less than those who are qualified and interested in applying.

(Is there a further lesson here that the imprimatur of their diploma –specifically cited in the tweet — just paved the way for a position. That happens, not in places where I’ve worked, but surely it happens.)

But this is not to say don’t generalize; in fact, I’m hardly the first to claim that generalization and the comparisons we then make are the bedrock on which thinking and action are built. It’s just that one has to be a little modest in doing so, and willing to own it.

Lesson 2 concerns part of our job, as faculty members, is presumably to be acquainted enough with our field as to make claims about it to those interested in entering it. In our Department the majority of undergraduate majors go on to a wide variety of careers outside the study of religion but there are those interested in considering working in a university and the graduate degrees that will be required. And, now that we have an MA program, some of those students are eager to apply to doctoral programs. So it seems odd to think of a faculty member so unaware of the current job market and requirements of further graduate education that they’re unable to mentor a student, at least in some fashion, who asks about all this. Just like being up on the current literature in ones field, it seems to me that being aware of current and larger institutional issues in academia is also part of our job — both within ones field and throughout higher ed as well.

So, I found the tweet’s response to that question very disappointing.

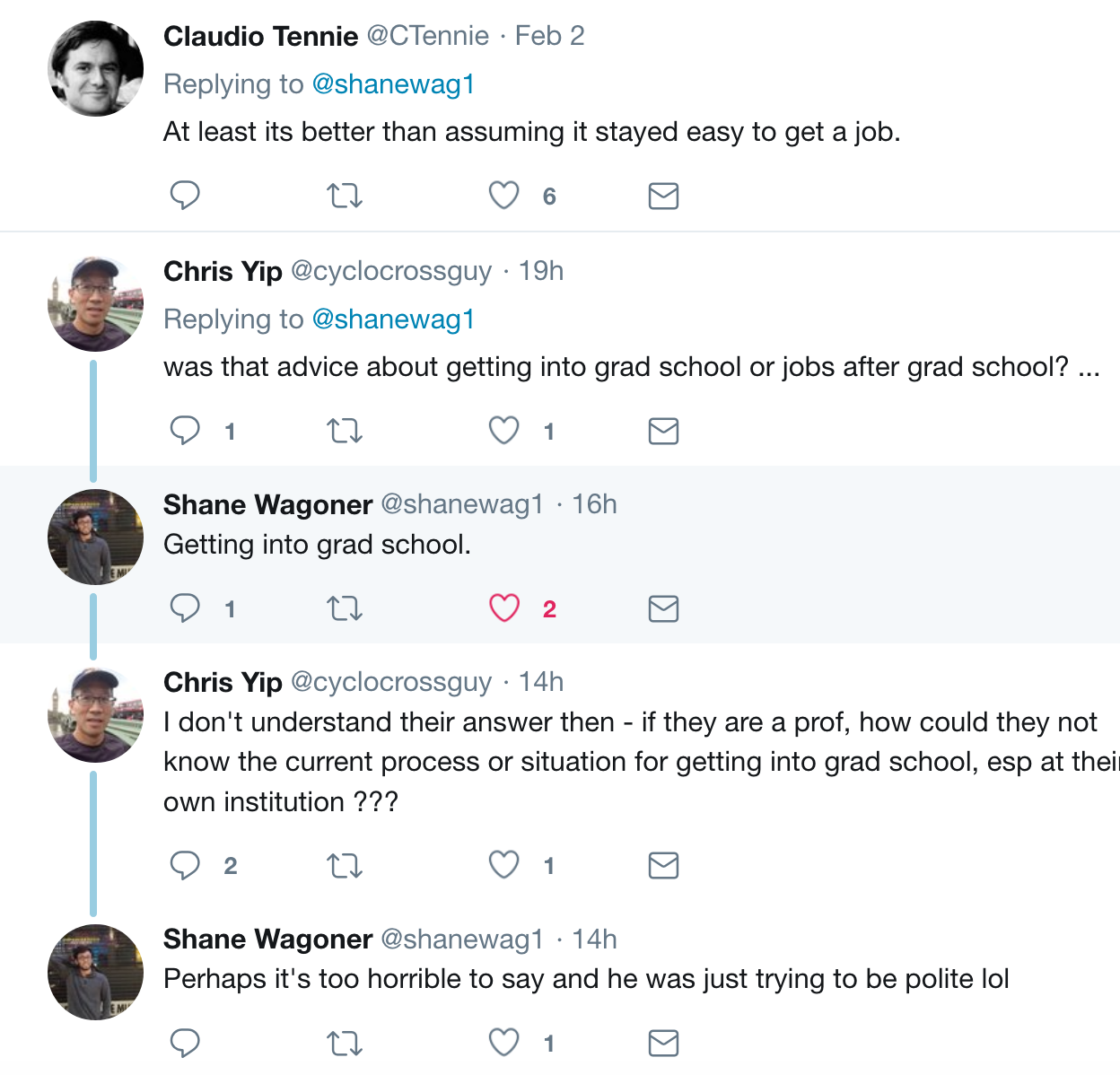

But this brings me to lesson 3: the diverse ways in which this tweet was read by others. For it you go to the original and then read through the comments you’re just as likely to find indictments of this episode as praise for the faculty member.

For example:

This is the only proper response and he should be lauded

— [holiday not found] Tyler (@t_konch) February 3, 2019

Or this one:

Points for honesty and candor

— Kelsey Utne (@kelseyutne) February 3, 2019

While I certainly understand how counter-productive and even harmful it can be to offer advice based on out-of-date and out-of-touch information — and thus how the above response is likely preferable to any of that — I’m still a little puzzled by these responses to that tweet. So I’m not sure what the third takeaway is, but I think it has something to do with how dispirited many current applicants are and how disillusioned they are with the academic generation ahead of them, thereby finding it refreshing to just hear someone from among those ranks not have anything to say.

I admit I’m rather interested how others read this thread…