The following is a recent post, to the Religion in South Asia list, from Prof. J. E. Llewellyn (reprinted here with his permission).

19 December 2018

Sisters and brothers,

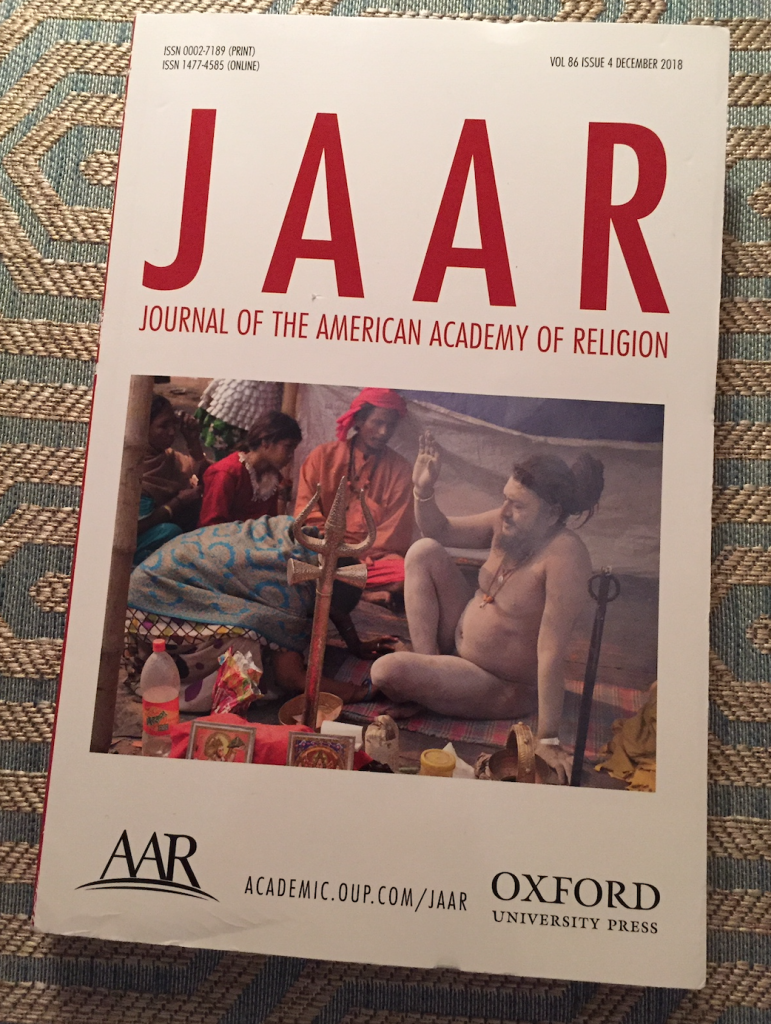

Since I have carped about a JAAR cover photo in the past on this list, I want to commend to your attention the cover photo of the issue that I just received in the mail (86/4 December 2018).

Though I am no art critic, I think is a striking photo. It is divided into two panes by a trishul. The main figure in the right pane is identified in the photo credit as sadhu. The subject of the left pane is a woman who is sitting on the ground and bowing at the sadhu’s feet. The sadhu’s pane is hazy; he is covered in ash, but there is also smoke, doubtless from a fire, but one that is not visible in the photo. The woman’s frame is clear. The woman herself reaches across the barrier between the two panes, with her left hand resting the on sadhu’s left foot. I could go on about the composition of the photo, and the compelling information it conveys.

The credit pairs the photo with the article in the issue by Amanda Lucia, though there is no indication that Lucia chose the photo—she does not mention it in the article. However, the image is apparently appropriate to the content of the article: the women in the photo seems to embody the disciple’s desire for physical contact with the guru, about which Lucia writes. The sexual aspect of Lucia’s article, that this regime of physical contact provides the cultural background for acts of sexual transgression by gurus, this aspect may be suggested by the fact that the sadhu is naked. Viewing him from the side, we are spared the sight of what Eliade once decorously referred to as the “membrum virile.” The woman in the photo, facing the sadhu, may not have been so lucky.

A quibble that I have with this photo is that sadhus are rarely seen naked, at least in my limited experience. So it is a bit of an orientalist image. A prominent exception to my claim is the Kumbh Mela, in which naga sadhus come first in line in the processions, and are frequently the subject of comment both in press coverage and in the public’s gossip—they are the stars of the show. In theory their nakedness is supposed to be an expression of their utter indifference to worldly convention. However, I often heard speculation that the nagas at the Kumbh were not always naked. On the contrary, people told me, and not always in jest, that they had certain evidence that at least some nagas shed their threads for the festival, in the visible tan lines they detected on their persons. Perhaps there is another article to be written (or that likely has already been written—I do know the etymology of Digambar) on the nakedness of Hindu holy men.

All the best for the holidays!

Jack

J. E. Llewellyn

Department of Religious Studies

Missouri State University