I’ve got to admit, I’m getting tired of all the “epistemological crisis” talk and the way it’s being pinned on the humanities in general and postmodernism in particular.

For the way I see it, members of groups that once benefited from a broad social consensus are now a bit angry that someone has pointed out the link between power and knowledge. Or, to rephrase, it’s curious to me how a socio-political issue is continually portrayed as an epistemological issue, as if this is all about how “we know” and not about “how we organize” and “who gets to organize.”

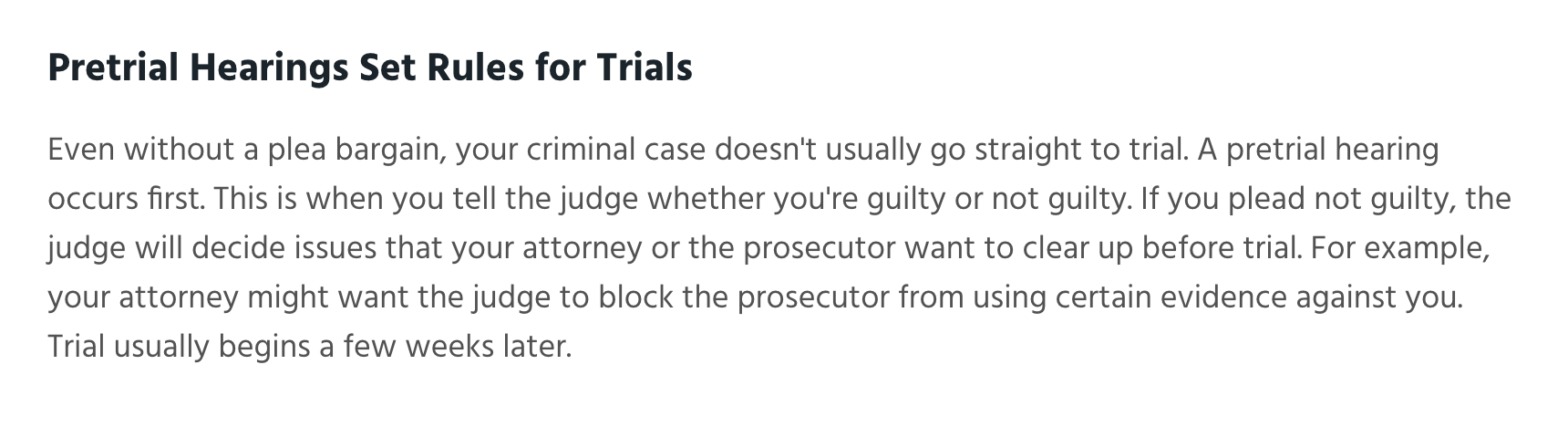

I’m tired of it coz we all realize — don’t we?! — that what counts as facts (or as they say, evidence) in a trial is all based on what the lawyers are able to persuade a judge to rule in or out during the pre-trial hearings.

As I’ve said on other occasions, you’d have to be really uniformed in how courts work to think that the so-called facts of the case were somehow self-evident, objective things just floating out there in space that somehow proclaimed their own significance. Trials would be dead simple affairs if that’s how it worked. But they aren’t, since each side in the case will argue, draw on precedent (or say why we ought to overturn precedent!), all the while using a variety of rhetoric skills, in order to get a judge (who, by the way, was appointed for who knows what all reasons, many of which might have had nothing to do with their legal acumen) to rule that, say, an old speeding ticket is or isn’t relevant for the purposes of the present case.

So even the staunch realists among us would have to admit that, at least in courts, the problem is that there are way too many facts and someone has to narrow them down — just as how, in tennis, there are way too many places where you could hit the ball, so we need to narrow it down. And so we draw lines on the ground, thereby inventing a delimited space that’s, yes, also called a court. Only within the lines can the action take place.

Both courts are invented and policed. In both cases we devise ways to make appeals. And then we just have to live with the decisions.

Or call the whole game into question — the chosen strategy of the US’s President, of course.

But the important point is that it’s the rules and the rule makers (or rule re-makers) that craft the limitless stuff of daily life into facts that matter; significance is a product of structure and not the other way ’round.

So if we all know this — we do, right?! The tennis lines don’t have to be where they are now, that can change… — then it’s all the more interesting how we overlook it when it comes to those things we call facts in other domains, and how angry some of us get if someone points out how the same analysis (on the socially constituted nature of so-called facts) applies to all sorts of other things in all sorts of other parts of life, thereby demonstrating how so-called epistemological issues can actually be understood as social and political issues.

So, as I see it, there’s no epistemological crisis and calling it that is part of a rhetorical strategy that gets us thinking about brains rather than bodies. Instead (and I’m hardly the first to say this), it’s an issue of authority — who gets to say what stuff counts and what doesn’t. There’s been a significant social realignment, over the past few decades, that’s still getting worked out and so not all the players respect the old ways; who knows where it is all going, but it seems to me to be more about people, groups, interests, associations, actions, and alliances than it does about some seemingly disembodied thing called knowledge.

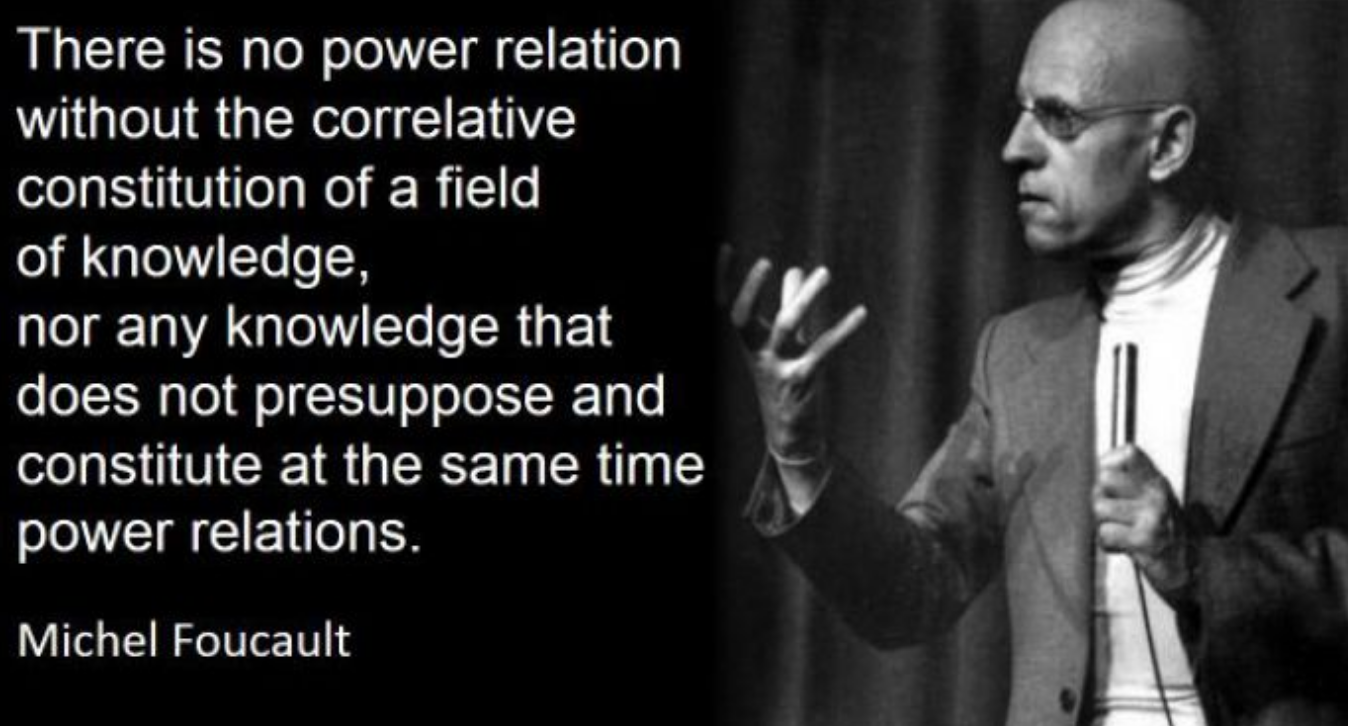

But then again, someone else said all this back in the mid 1970s, didn’t they?