Last week I wrote a post on some strategies to think about when applying for academic jobs. As I wrote there, I’ve played the role of Chair long enough that, like many others in the field, I’ve learned a thing or two from being on this side of the interview table; and so, with interview season quickly approaching us, I thought that a sensible follow-up should be some reflections on the on-campus interview, as seen from the Department’s point of view.

Last week I wrote a post on some strategies to think about when applying for academic jobs. As I wrote there, I’ve played the role of Chair long enough that, like many others in the field, I’ve learned a thing or two from being on this side of the interview table; and so, with interview season quickly approaching us, I thought that a sensible follow-up should be some reflections on the on-campus interview, as seen from the Department’s point of view.

(And, as I wrote in that earlier post, my hope is that others get in touch with us to write a guest post or two of their own on these very topics. For views and practices obviously differ and more is better when it comes to getting information to prepare for the job market.)

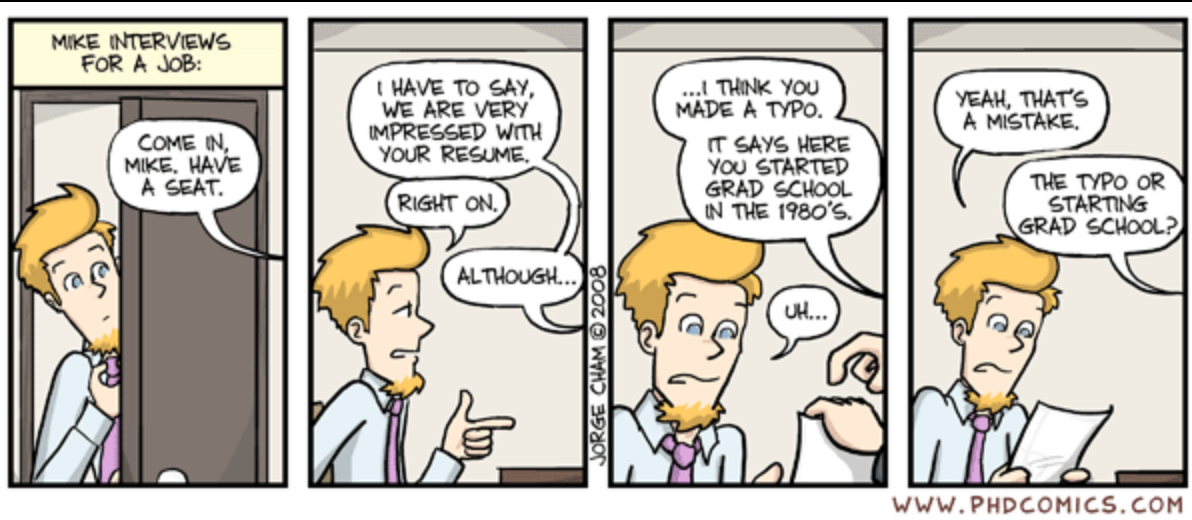

First off, that opening cartoon has it wrong, I think.

Sure, I bet there are faculty out there who zero in on such things when interviewing people on campus, all in order to score a point or to upend them in a game of gotch’a; academia, after all, is not immune to the sort of bravado that we easily see in other fields. If anything, our chosen career might be even more prone to it, given how scarce the resources (whether social or material) can sometimes be, driving up the competition along with the professional preening. For we’re all pretty insecure in our position, given that our expertise, being narrow, makes all too evident to us just how much we don’t know. But in my experience, while the on-campus interview is certainly an opportunity to confirm, in people’s minds, the credentials that they saw on paper when you first applied, it’s generally not about credentials for the faculty welcoming the interviewee to campus.

As I’ve often said to people when answering questions about this, the credentials are now a given. That’s what got the two or three candidates to campus; now its likely about something else.

I could call these new criteria intangibles but that opens the door to all sorts of slippery and undefined subjective criteria that, I’d argue, don’t really have a place in the hiring process. In the business world these days they’ll often call them soft skills, but, like the distinction between the so-called hard and soft sciences, I’ve got my reasons to steer clear of that way of talking about mastery. I could say collegiality — though, not unlike that term “cult,” it’s a word that today so easily slides into troublesome and unprofessional uses that it isn’t all that helpful either. A subset of what I have in mind might be called pragmatic skills, but what if we just called it being a colleague (something I’ve written about here before) — a term I’m using to distinguish from the “just go along with it” connotations that sometimes come with talking about collegiality (a problem in the field that Aaron Hughes and I have addressed in a co-written, forthcoming book chapter, actually). As I see it, being a colleague means someone who can bridge what others see to be a gap, maybe even an irreconcilable contradiction: being a self-motivated scholar who also works in collaborative social settings (everything from classrooms to committees). As I’ve written elsewhere, we’re not self-employed, despite how some faculty act, but, instead, we work within institutions that not only establish the conditions of our labor which which have needs of their own — someone has to advise students, after all, and that annual public lecture your Department hosts doesn’t magically plan itself.

(How this all applies to non-tenure-track, contingent faculty is certainly a topic to consider; while being more than aware of this, for the time being I’ve got tenure-track campus interviews in mind.)

So if that’s what I mean by a colleague, then for me, sitting where I sit at the interview, the campus visit is an opportunity to think about someone in that role, by meeting them in person, spending a couple days trying to get to know them better, while seeing them interact with other faculty, staff, and, yes, students as well, doing so in a variety of venues. It’s a short visit to campus, of course, in highly artificial situations, and, at the end of the day, there’s a speculative judgment that inevitably comes into play; confident that the person has the credentials and the technical expertise (otherwise, why invite them to campus?), we’re interested to gain some evidence as to whether candidates can put those skills to work in practical settings that mimic a classroom, a faculty meeting, a more informal social occasion, etc.

While I’m not sure what others think of this, of course, the paces through which campus visitors are usually put seem to support this reading; for, like I said, the contrived moments included on many itinerary generally constitute typical moments in the social life of a Department — how do you interact with other faculty and what did the students make of the class you taught? While (as in that opening cartoon) I can easily imagine someone intent on the details in the paper an interviewee might present (if a so-called job talk is part of the process — it isn’t always), I can just as easily imagine others not caring all that much since it’s likely on a topic of which they know very little — but I’d imagine the faculty in this later group are nonetheless still listening intently, but for something else: can the person string together ideas in a developmental and persuasive sequence, are they attentive to their audience, did they gauge their listeners correctly (after all, we’re all relatively bright people but, like I said, we probably don’t know all that much about what you in particular do) and, when it comes to the questions, does the person know how to engage in that casual back-and-forth banter that, at least when I go to conferences, is sometimes so painfully absent during the Q&A? (Aside: upward inflection at the end of a sentence doesn’t really make extended soliloquies sound like a question.) Or, to put it another way, while there’s surely stakes for someone on this or that detail, the job talk is likely not a joust or a death match and does the person we’re about to add to our team understand that?

(Sure, my hope is that the people doing the interviewing know that too — by the way, this post is as much for them as anyone else.)

When it comes to the classroom (an element that’s not always part of an interview), the fabricated nature of the entire exercise is pretty obvious there — if it wasn’t already — for faculty don’t often silently sit along the back wall of each others’ classes. (Though, in our Department, a senior colleague sits in on all earlier career faculty’s classes, at least once a year, meeting with them afterward to talk over the class and producing a memo that they can use in their annual applications for re-appointment.) Sure, it can be a little unnerving for applicants, but the biggest mistake I see made here is (literally or figuratively) talking over the students’ heads by addressing those people assembled at the back of the room. For while I’m not sure what others think of their role along that back wall, I seen mine as trying to judge whether the candidate can teach undergrads (something pretty important to many Departments), which generally means starting where 19 year olds are and moving them to a novel place, equipped with some knowledge that they didn’t have at the start of the class. There’s only 50 minutes or so to do this, sure, so I’d better be realistic for what I think the applicant can accomplish, but is there evidence here that they know how to do this — or at least that they’re going down the right road and can get better at it? Instead, given what I do in my work, I’ve sometimes had candidates pretty clearly pick up on topics I’ve worked on, teaching a class but pretty much talking past them and directly to me throughout. And, at least judged by what I’m looking for in a sample class, that’s a hit that’s pretty far off the mark.

Come to think of it, both the job talk and the sample teaching are pedagogical moments, for, like I said above, it’s likely the case that both audiences don’t know all that much about your specialty. Can you bring us along, whether it’s faculty listening to your paper or students listening to your lecture? Both groups know what it means to be talked down to, you can bet on that, so, as I said earlier, can you meet us where we are now — rather different places for these two groups, to be sure — and then help us, over the course of an hour or so, get somewhere new? Knowing something about what the faculty all work on will likely help you figure out a way to do that in your job talk. (Hint: how well have you researched us before getting here? Do you have questions about what we each do?) Asking what the students in the class are currently working on and getting their syllabus can help with planning your class, even if you’re not asked to teach anything directly related. Both help you to gauge your audience.

Apart from those two moments — the job talk and the teaching — there’s a wide assortment of other situations into which candidates will likely be put on their campus interview, from handshakes at airports and chats while driving into the city (unless a shuttle van picks them up) to coffee breaks or lunches with grad students, meetings with more senior administrators (where broader Human Resources topics might get discussed), and breakfasts or dinners with faculty. While it may go without saying, in my experience it doesn’t, not for everyone, so I’ll just say it: it’s all part of the interview. Students are queried on their experiences with interviewees, whether in that teaching demonstration or after they’ve had a coffee chat; Associate Deans often send feedback of their own based on their interaction; the grad students are asked for their thoughts on the person they just met. Often, students are uniformly complimentary, which is nice and generous on their part. “There but for the grace of God go I” the grad students might be thinking to themselves, but you may be surprised how an undergrad in a sample class can sometimes zero in on a key issue, in the anonymous comments they’re invited to submit immediately after that class.

And yes, we read those comments.

As for the meals, no less part of the interview, it can be a minefield for the applicant, to be sure, but it can also be the setting for an informal and even fun discussion. I’ll leave to you to decide if what you order is relevant (some people steer toward things easily eaten as opposed to rolling up your sleeves and wearing a lobster bib), or whether you should order a drink. Personally, I’ll sometimes order a drink for myself (and not really finish it, to be honest) just to try to signal to the candidate they they’re free to have one as well. We’re all adults, after all. But it’s still a job interview, and I can imagine sound arguments for steering clear of any alcohol. As silly as those business school seminars on how to attend a business dinner might strike some of us, it’s likely a moment in the interview worth thinking through in advance, inasmuch as unintended but still significant social information can be easily gleaned over dinner with someone. (I could tell you stories about professional dinners, like the time — not at a job interview dinner, mind you — when someone else at the table asked to finish my drink.)

At our school there’s also an element to the campus visit — voluntary for interviewees — that involves meeting people outside the Department that’s doing the search. Intended as a chance for visitors to ask a few questions that they might not float to the Department, it pairs faculty participants in other units with the candidate (they may share interests, etc.), for a coffee or a breakfast, aiming for whatever they discuss to remain between them (i.e., I don’t hear about these meetings but, if an interviewee is game, we steer them toward the site to set it up and we then include it on the visit’s itinerary). Making a move is a big deal and we’re aiming to get them as much frank info about the school, the city, the region, as we can.

And then there’s the exit interview — not always included, it’s sometimes a chance to talk to the Chair, alone, at the end of the process, where things like tenure and promotion criteria are discussed, where moving expenses and starting salaries could be mentioned (often that’s not even addressed til an offer is made; how to negotiate that is an entirely separate post), along with teaching duties and service expectations, etc. Sooner or later, whether here or elsewhere during the visit, you’ll hear the old “And do you have any questions for us…?” — while it can be a polite signal that “we’re done here” it can just as easily be a sincere attempt to elicit queries from the applicant, a person bound to have lots of questions about the place. Are you prepared for that question? Have you been asking questions all along, about the Department, the University, the city? Here’s your chance, now that you’re here in person, to ask about the local elementary schools or the Department’s sabbatical policy, let alone a host of other things that, should you be lucky enough to get an offer, you may rely on later when making a decision about where you’d like to spend part (or all) of your career.

(Like I said, there are some questions best left to the negotiations that come with an offer — the moment when you, the applicant, are in as privileged a position as you’ll ever be in this whole process and thus the moment when you likely should ask for whatever it is you want or need. And knowing when to stop asking and make a decision is itself a skill that communicates information.)

But having said all that, the mindful faculty among us know that we’re being interviewed by applicants too, so we’d be wise to be on our best behavior as well. She might get more than one job offer or he might decide not to to come despite our offer. So while the power imbalance is pretty evident in the campus interview, it may be more complicated than applicants realize, since some sub-fields today constitute a seller’s market, given how few specialists there are, despite the pretty obvious job market conditions that, for several decades, have swung in the favor of those doing the hiring in the Humanities. So, during these interviews, a wise Department is working hard to put its best foot forward as well — scheduling a real estate tour maybe, a campus tour or tour of the library, or offering to bring someone back to town if they’re the finalist, so they can look around for a place to live. Maybe even we, on our side of the table, consider not ordering the messiest thing on the menu.

Of course there’s a whole series of incalculables in all this — e.g., what unstated, internal arguments are you in the middle of as you start to answer a question after you give your paper. (By the way, I’ve been in Departments where we all sit around a table and actually interview you, asking questions one at a time, and I’ve also been places where the Q&A after your paper is the most formal interview that happens.) While being careful in how you present yourself you’ve got no choice but to just go for it, being true to whomever you see yourself to be or wish to become in that position. After all, who wants to get a job where the Department expects you still be the person you pretended to be at the interview? But knowing that Departments, like families, have their own complexities means that you’ll be wise to consider how you answer or how you represent yourself; and its that consideration that might be evident to other members — not necessarily long pauses but answers and representations that make evident that you realize there’s a diverse team on the other side of the table, to which you can make a contribution.

And with those incalculables in mind, I have an anecdote of my own to close this post (keeping in mind how I closed the other, by borrowing one from a friend). Mine involves not the times when interviewees have taught intro students by throwing multi-syllable technical terms at them (“… the ontological phenomenon’s metaphysical anthropomorphism…”), as if it was a comp exam, but, instead, while sitting at the back of a sample class some years ago, watching an applicant teach, which entailed showing a brief movie clip to start off a discussion. As I recall it, the image was a little light on the screen and so the applicant instinctively reached behind to turn down the lights in the room, so the image was more evident to the students. You may be surprised how much that small gesture spoke to me, for it said that in the midst of that high stakes moment and while that candidate inevitably had a bunch of other windows open in their head (when will the clip be done? where do I go next? is that student gong to ask a question? remember to ask her name and try to retain it in case she talks again, etc.), that person was mindful of the seemingly mundane conditions of the classroom itself and how that might affect the students’ learning. It told me that the person knew some things about what it means to teach — evidence of which I was looking for, sure, but I didn’t expect to find it in such a seemingly inconsequential gesture. Luckily, I was paying attention and noticed it, because it told me something that the person surely didn’t realize they were saying about themselves and it was significant and helped their case.

With that anecdote in mind, the campus interview is a good example of a structured moment in which the agent has little control over many things, though retaining much control over others. Doing your homework in advance helps as does selecting a job talk and a teaching topic with which you’re really comfortable and familiar. (We never assign these, by the way.) You clearly don’t know all sorts of variables that are at play in that brief, two day visit to a school, and the interviewers might not know all of them either. But the prep pays off along with the ability to adapt to the unpredictable in these moments — as does setting a couple alarms so you don’t miss an 8 am breakfast meeting.