The MacArthur Foundation recently announced the 2017 recipients of its so-called “genius” grants, a five-year fellowship of $625,000 awarded to individuals of “extraordinary originality and dedication.” Among them was a composer and musician Tyshawn Sorey, who is “defying distinctions between genres, composition, and improvisation in a singular expression of contemporary music,” according to the Foundation’s website.

Where does his inspiration to “defy distinctions” come from? Some of it is Buddhism, the composer says in one interview. When asked “how other art disciplines affect his work,” Sorey responded:

Well, besides art disciplines…Zen Buddhism, literature, and painting has had a very profound affect on my work in many ways as well as the way I listen to music, which is really no way at all – positively speaking. Those two things are the primary generators for my work, as well as the experience of everyday life…which, for me, is improvisation in all senses.

Zen Buddhism shapes the way he listens to music, which is “really no way at all – positively speaking.” There is a “way-less way” to listening, experience, and improvisation. With this oxymoron, Sorey invokes the dominant image of Zen (and Buddhism), which is radical non-dualism, total spontaneity, and positive emptiness. In the same interview, he elaborates on this Zen-inspired world further:

… it was only natural for me to simply listen to the music for what it was. I mean, there was never any real “way” I became aware of my interests in music and creating, because it was already there from the get-go. … later discover that I became somewhat of a “jazz purist”. It became apparent to me that I was listening to music in one “way”; that it was time for me to eliminate the idea of taste, likes, and dislikes and take from whatever I listened to and let it be a part of my musical makeup. I believe that every listener of music listens in their own way, and I did not want to listen in ANY WAY…but to JUST listen – no feelings that “something sucks” or “something is catchy”, etc. then, my tastes would not let me fully experience what was happening in the moment. To listen to something without “listening”.

Here, then, is one face of Buddhism that is gaining more traction in the contemporary West (if the award of “genius” grant is any indication of social currency): countercultural simplicity (“simply listen”), pure experience (“jazz purist” “fully experience”), and flow-like immersion in nothingness (“no taste,” “listen without listening”). The discursive undertone of Sorey’s answers echoes what David L. McMahan called “Buddhist Modernism,” which constructs Buddhism as a practice of the free spirit. “… Buddhism is a religion in which you don’t really have to believe anything particular or follow any strict rules. … Buddhism values creativity and intuition and is basically compatible with a modern, scientific worldview” (MacMahan 2008:4).

And here is a sample of Sorey’s music which, as the title (kōan, a zen style of questioning) and album cover indicate, has been inspired by this Buddhism:

Did it sound Buddhist to you? Does this count as Buddhist – to whom and how?

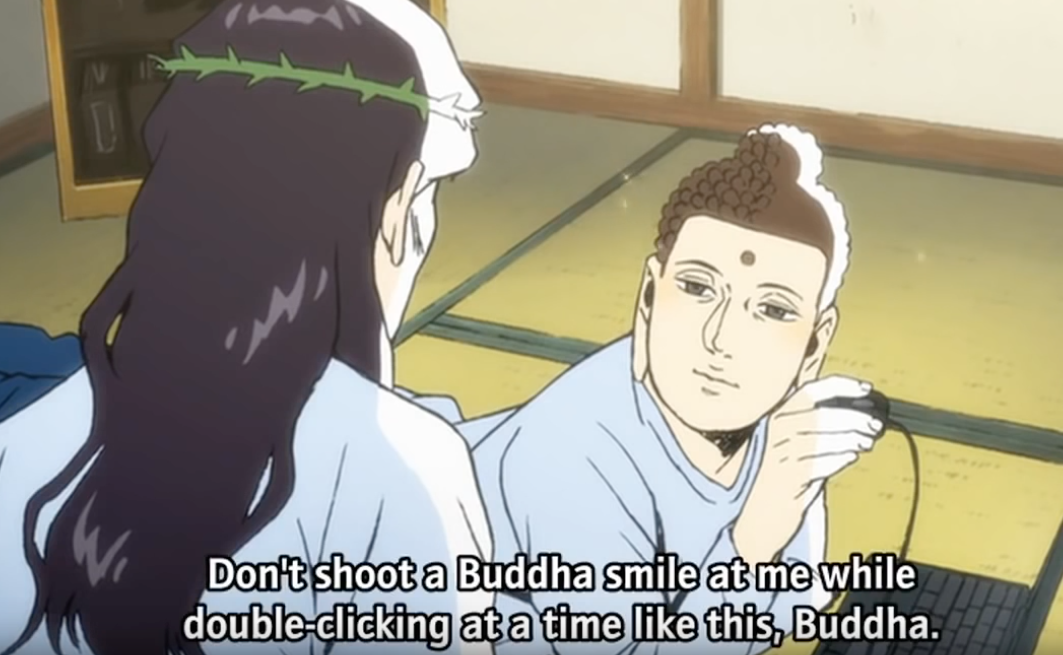

It is perhaps ironic, then, that in the nation known as the founding place of Zen, another face of Buddhism has been gaining much media attention and popularity. Don’t get me wrong, the narrative of Buddhist Modernism is in Japan, as well. But here, I’m referring to Saint Young Men, the comic-turned-anime that won the prestigious Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for talented comic artists in 2009. This “heartwarming comedy” (from the comic cover) tells a story of Gautama Buddha and Jesus Christ living as roommates in a humble apartment in a Tokyo neighborhood. They are, the comedy goes, “taking a vacation” from their demanding godly duties to enjoy the unfamiliar but exciting life of regular humans. Here are some quick scenes:

The anime makes fun of widely-known concepts associated with Buddha and Buddhism among contemporary Japanese people, such as compassion (“Buddha smile”) and enlightenment (“truth of the universe”). The humor is in the placement of these highly idealized values within the daily life of imperfect human beings. This Buddha “shoots a Buddha smile” while double-clicking on an internet website and comes closer to “the truth” in a public pool’s communal shower. He is deeply human and yet not just human, and this tension leads the audience to laughter.

Clearly, this Buddhism does not emphasize the qualities of Zen-inspired Buddhist Modernism. It does not advocate pure experience, total spontaneity, or countercultural emptiness, and when it brings up such stereotypical notions, it mostly does so to poke fun at them. Some readers may be surprised that this kind of anime comes out of a country that is, statistically speaking, majority Buddhist. Actually, many people who say their affiliation is Buddhist simultaneously assert that their self is “non-religious” in Japan. This is a result of the modern history of encounters between Japan and Western nations, during which the country’s elites popularized the idea that some Japanese “religions” were not really “religions” because they were not about inner conviction but about public ritual (See Hardacre 1989, Josephson 2012). ” Consequently many people who identify with the narrative of “non-religious Japanese” associate their Buddhism not with their internal belief or essential identity but instead with the realms of “family,” “tradition,” “kinship,” “ritual,” “history,” and “culture.” To such people, it is entirely sensible to claim that “my family is Buddhist but I’m non-religious.” There is some distance between “Buddhism” and “‘me’ as the inner subject” in this kind of cultural framework.

So perhaps the contrast between Tyshawn Sorey’s Zen-music and Saint Young Men‘s comical Buddha reveals not just the multiplicity of Buddhisms but also the multiplicity of Buddhist modernities—that is, the ways in which people in different parts of world use “Buddhist” themes to reach out to their visions of the world.

** An earlier version of this post spelled “Hardacre 1989” incorrectly. It was a typo due to carelessness, and the author sincerely apologizes.

**Professor Ikeuchi is teaching REL 372: Buddhism in the Spring 2018 Semester.