Katherine Reed is an Environmental Engineering Major with minors in Mathematics and Religious Studies and is from Las Vegas, Nevada. The following was written for REL 360: Popular Culture/Public Humanities.

Laura Levitt, from Temple University, gave an amazing and interesting speech entitled Objects Out Of Place: Revisiting the Sacred Arts of Holding, Custody, and Conservation, that focused on everyday objects that become almost talismanic as a result of the events they have endured. Much of her lecture comes from her studies on holding and custody in police evidence lockers and of the haunting remains of the lives of victims of the Holocaust. Items like shoes, eyeglasses, and the clothing of a murder victim: a wool jumper and pantyhose, are all things that we do not find particularly special without assigned knowledge or context that tells us what they meant for those who used them when they became frozen in time by violence.

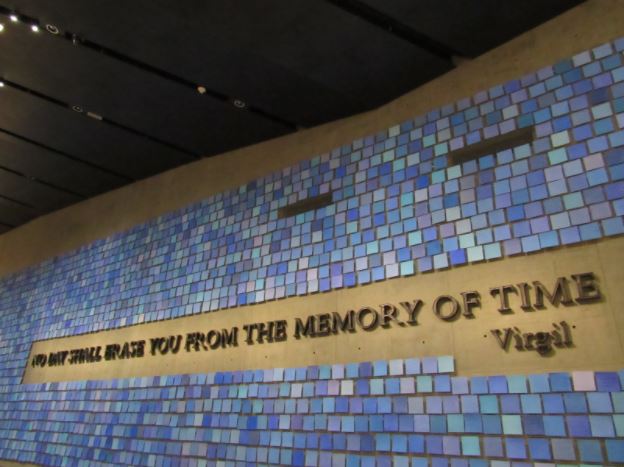

Following her presentation, Levitt allowed for questions from students and staff and gave some insightful answers complimented by her vast research and interest in the information. One student asked about whether or not the process by which we make everyday objects talismanic can be reversed, making objects of meaning simply become objects again. We can make a material object mean much more than its simple usage, or return it to its original state through a magnificent combination of memory and forgetfulness that is entirely human. If returned to its state of emblematic uselessness, does an object that used to be considered talismanic bring some form of relief to a society? It is much more rare for an object to completely lose its meaning than it is to be changed and morphed to fit the needs and hearts of changing societies. Events riddled with terror and violence often inspire monuments, and a collective mental connotation that allow us to move on (whether we ought to or not is constantly debated) to a state of solemn pride and survival.

What is the difference, then, between objects preserved through society as emblems of struggle and objects we consider to be heirlooms? I believe that in this case, one would need to turn to those who are claiming an object to be in one way or another sacred and how that object came to be. Connotation is increasingly important as well. One may call an object an heirloom as an example of values or pride in a family, group, or nation. It would seem scary to us to hear someone claim remnants of the Holocaust or the clothes of a rape victim as an heirloom. There is an exchange, a social agreement, between objects and people (and their known or unknown intentions) that forms an image for both in terms of representation. Because this connection is so loose, we make objects important and meaningful very often. It is easier to study and see those incidents that are more wide-scale, but we do the same thing to items in our homes and on our shelves, carried throughout generations, to gain importance. An example of this frequent, yet smaller, tie between objects and people is a mirror or a desk that belonged to your great-grandparents. However, there is something special about those talismans created through violence, and it is because we give it the authority it needs to create the effect that Levitt speaks of.

Laura Levitt also spoke on recreation and reconstruction as means of preservation. When asked if she thought some meaning or part of history was lost by attempting to recreate it, Levitt answered that a recreation will never be perfect, but can carry the parts of history that hold a deeper meaning into today’s society. Would the parts of history that the objects represent be carried forward had the objects not been preserved? We constantly pull from the past, making the present a recreation of what we “know” of the past. I believe that making an item, an emblem, is our own way of marking where and when history occurred, making them something to remember for generations to come. We can’t tell what really happened in the past because we were not there, but we know, to some extent, that we use the past. Making talismans can therefore be considered a way that we try to keep a part of history that we experienced, from being permuted.

On this note, one part of Levitt’s speech spoke very powerfully to me. She said that things that are older, that carry meaning, and that we mean to preserve, are usually being eaten away by the very things that make them meaningful. An object that is dirty or rusted can not be cleaned and preserved correctly without stripping it of its past, thus losing some of that talismanic meaning that Laura spoke of. This note brings some final questions to light on Levitt’s lecture. Is it our job to preserve the past? What are the consequences should we not?