Sierra is a recent graduate of our B.A. program with a double major in Anthropology and Religious Studies and a minor in Spanish, and she plans to continue working with us to pursue an M.A. in the Fall. She has previously produced independent research on cemetery artwork and the category of myth at the University of Alabama and worked as a research assistant for a variety of groups and projects at UA during her undergraduate career.

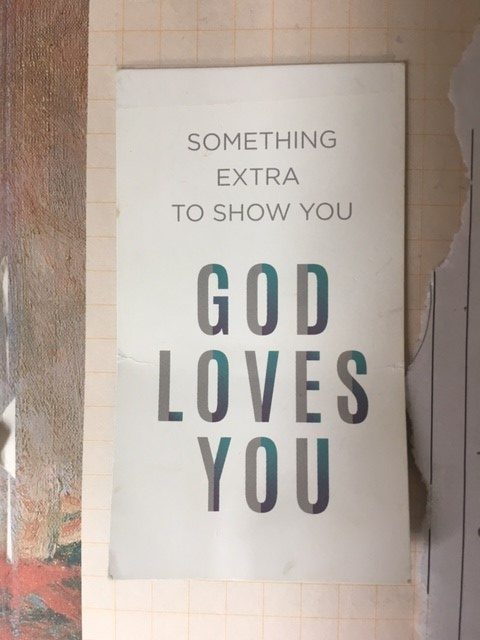

Recently, I was denied closure at a Starbucks drive-thru when a specific group, working within the structures of society, interrupted my daily caffeine ritual. As my 1997 butter-colored vehicle creaked to the pick up window, the hand that usually supplied me with my beverage was instead holding a bright card with bold turquoise lettering that read “Something extra to show you God loves you.” Operating within the structures that favor standard American English, my barista briefly explained my purchase had been taken on by a third party as my drink mechanically moved from their hand to my cup holder and I pulled away.

The Starbucks drive-thru at the intersection of Hackberry Ln and 9th Ave follows the seemingly universal protocol for drive-thrus; signs guide patrons through a series of actions essential to yielding a successful interaction and the transmission of capital for goods. The complicated combinations of flavors framing each Starbucks experience as spontaneous and unique are dictated by broader structures informing what we order and how we order it.

Émile Durkheim, the revered French philosopher born in the 19th century between Karl Marx and Max Weber, coined the term collective conscious(ness). In this notion Durkheim dissects the many facets of human interaction he believes are essential to creating and maintaining greater structures that are the fabric that unifies society. Durkheim posited religion as a mechanism for explaining the constant rhythms of society and engendering it with significance in the group’s collective consciousness. Within this framework, rituals serve as the embodiment of a collective belief that the delicate balance of the world is contingent upon our behavior.

We are constantly operating within and internalizing structures to create a mosaic of values we embody in our daily lives. Whether it is capitalism or the gender binary; we are constantly identifying with systems that determine the values that are favored and operationalized in the global marketplace of ideology.

Target before 10 am is comparable to this theoretical space – as during the early hours workers stock aisles with products that appear to have self-materialized during other hours. More often than not, we are completely unaware of the agents deciding which meticulously packaged stock is present on the shelves from which we draw ideas regarding the workings of the world. Even if we catch a worker stocking the shelf, it is unlikely we understand the complexities that have been naturalized to allow us to make decisions that are predetermined but masquerade as moments of agency.

Conduct in certain contexts, such as the Starbucks drive-thru, is regulated so membership in a group may be easily performed. The group may be socioeconomic, racial or gender and each have their own expected behaviors based on dispositions about them. After all, we must be able to afford a car, gas, and expendable capital as well as possess the skills to maneuver the vehicle before we are even granted access to participate in the rituals that result in our own personalized cup of joe.

The omnipotent agent that paid my debt was identified on the back of the card as the Church of the Highlands, and the interaction ultimately left me frustrated. Instead of performing my identity within the boundaries upheld by dominant ideologies, I was too perplexed to respond at all, let alone with gratitude. I was the outlier behaving inappropriately by failing to participate in the system of reciprocity that was implied by their material gifts. The tacit curiosity that comes with doing studies in the humanities forced me to probe the causes of cultural phenomena.

Thinking back on my gaping mouth that resulted of my interactions with the Church of the Highlands, it still seems like the appropriate response. Not because it is what was expected of me, based on the collective consciousness of my respective environment, but because it represented a break in the ritual that reaffirms the authority of certain groups to express their religious beliefs.

Certain groups are permitted to articulate their agency because of the system constantly determining which ideas become operative within societies and factions of society. It is entirely plausible such acts of self-promotion serve as central tenet for their sense of self, as they are an expansive mega church with a wide following across central Alabama. Had the card read “Something extra to show Allah loves you” would it have been as well received by other patrons of the local Starbucks, or would it have made national news? Or, even more plausibly, would the group be denied the right to pay for others and distribute religious material by the mega corporation that has previously been under the knife for ‘hating Jesus’ by discontinuing their holiday cups. Would this denial be viewed as a breach of their first amendment rights? By considering the inevitably insidious consequences a marginalized group might face upon performing a similar act, the privileges of certain groups are more obvious.