Ting GUO received her PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Edinburgh and has worked for the European Studies Centre, University of Oxford and the Center on Religion and Chinese Society, Purdue University. She is interested in questions of human autonomy and political freedom within the conjunctions of religion, culture, and society, and how the structure of world powers is manifested in the intellectual interpretations of critical social theory and philosophy. She writes bilingually and contributes for outlets including Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently working on a project on how “love” as an affective concept made its way into the Chinese vocabulary where previously such meaning was absent, and the ways in which it has been appropriated as a political discourse and a social force in modern China.

Ting GUO received her PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Edinburgh and has worked for the European Studies Centre, University of Oxford and the Center on Religion and Chinese Society, Purdue University. She is interested in questions of human autonomy and political freedom within the conjunctions of religion, culture, and society, and how the structure of world powers is manifested in the intellectual interpretations of critical social theory and philosophy. She writes bilingually and contributes for outlets including Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently working on a project on how “love” as an affective concept made its way into the Chinese vocabulary where previously such meaning was absent, and the ways in which it has been appropriated as a political discourse and a social force in modern China.

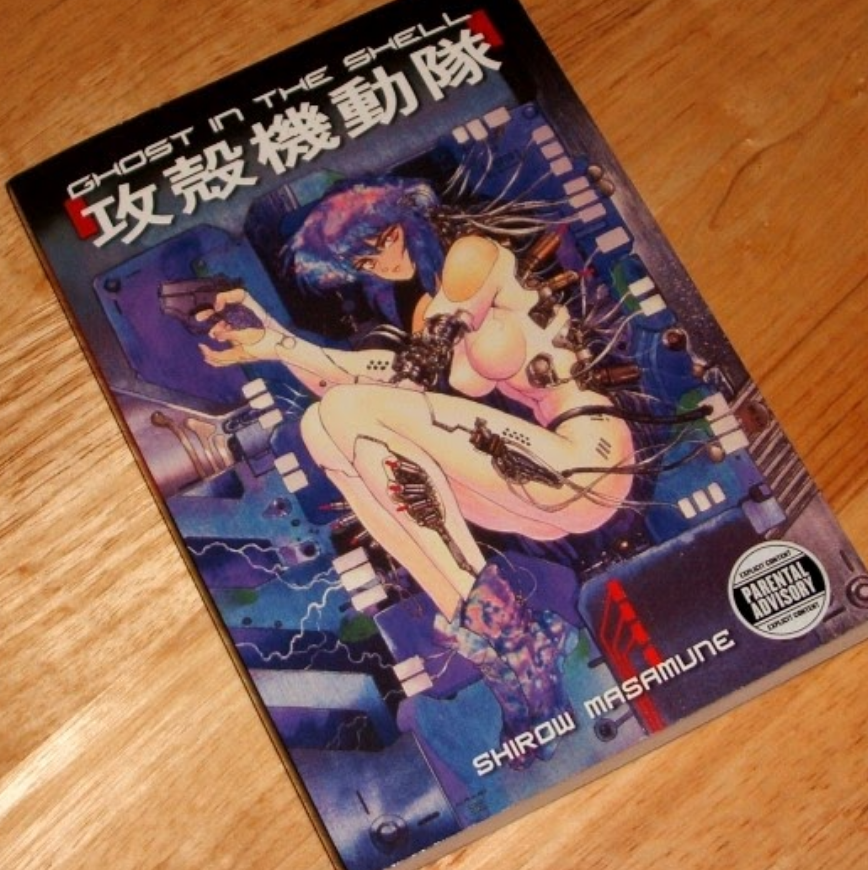

Based on the bestselling manga Ghost in The Shell 攻殻機動隊 (1989), Hollywood released the film version of it with the same title in April 2017. It attracted not only curious eyes, thanks to the casting of Hollywood star Scarlett Johansson, but also sci-fi lovers and thoughtful audience who reflected on the cultural dynamics of this production. Many of our Religious Studies colleagues, for example, detested the casting of a white woman (Scarlett Johansson) to play a Japanese girl despite recent debates and protests on racial issues in the US.

However, it would be too easy a critique to dismiss Ghost In The Shell as another Hollywood whitewashing. The original manga itself arranged the “shell” of Motoko, the protagonist, to be a hyper-sexualized Caucasian woman, which follows the tradition of most Japanese manga. The imbalanced structure of world power does not merely lie in how the West dominates the ways in which the rest of the world thinks and conducts their politics and economics, but more importantly, in how the non-Western world has inherited the aesthetics, ethics, and the shadow of such power.

Here I will briefly review the issue of gender and power in Japanese manga, in particular as Japan struggled and negotiated with Western powers in the nineteenth century and after the WWII, since the film is based on a manga. Both the manga and the film are set in settings that resemble sites in a cyberpunk, and in reality the fictionalized Hong Kong. This makes me think of Hong Kong’s current political situation, and entices me to analyse it in the context of this film.

Power and Sexuality in Japanese Manga

The term manga was coined by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), a prolific ukiyoe artist from Edo period (1603-1868) who left over 30,000 works. He was the creator of the woodblock The Great Wave, which brought him the fame of the first internationally recognized Japanese artist and The Great Wave is almost identified with Japanese art. He coined the term manga with two kanjis: man 漫, meaning “in spite of oneself,” “lax” or “whimsical,” and ga 畫, meaning “picture.”

Writing on the history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society, Kinko Ito notes that like any other form of visual art, literature, or entertainment, manga is immersed in a particular social environment including history, culture, politics, sex and gender. Manga also depicts social order and hierarchy, sexism, racism, ageism, classism, and so on, in particular when Japan became war-oriented and feudal. For instance, a certain genre of ukiyoe was popular during the Tokugawa period: shunga (spring drawings), woodblock print pictures with explicit sexuality and eroticism. Shunga also served as sex education manuals for new brides-to-be. This tradition implies the domestic position of women as they had little social space or opportunity of learning other than from those drawings. But shunga also indicates the fact that sexuality was not an unfamiliar theme in manga as a genre.

Manga was a popular art that permeated people’s everyday lives, and it also recorded the changes of Japanese society as Japan was exposed to and conflicted with the Western world. As Ito points out, Charles Wirgman (1832 – 1891), a British correspondent for the Illustrated London News from 1861 to 1887, reported several important historical events of the day in his magazine Japan Punch, including the bombing of Shimonoseki by the fleets of Britain, the United States, France, and Holland (1863 – 1864). This was also the time when Western ships made ominous visits to Japan, demanding that Japan open its ports. The Japanese government was obliged to sign unequal treaties with the West, and the power of the government began to decline—much similar to the Opium Wars (1839-1860) and its aftermath in China.

In the 1920s and 1930s many manga artists traveled to the United States, then the leader in comics in the early twentieth century. At the same time, along with new printing techniques that replaced woodblock prints, new comic and art styles and aesthetics were introduced to Japan, including the portrayal of bodies and gender norms. This was on top of the historical tradition of idealizing male dominance and female submissiveness. Moreover, manga developed into two genres, shōjo (girls’ manga) or shōnen (boys’ manga). Shōjo tend to have artwork that is dreamier and romantic and focus on human relationships, while shōnen tend to be brasher and flashier and focus more on competition or contests of will.

Many scholars have written on the reproduction of gender and power in manga. For instance, reflecting on Sailormoon, an internationally popular manga turned anime, Mary Grigsby notes that all sailor girls are hyper-sexualized and look the same, except for their different hairstyles and colors. Not only that women are interchangeable without characters, and it is their womanhood that matters rather than their specific embodiment of a woman. This was not only a result of the gender and sexual structure embedded in popular art; manga were further influenced by American cinematic expressions and images in the early twentieth century, which often consists of exaggerated normative heterosexuality with hyper-sexualized female bodies, overly emphasized masculinity, and patriarchal gender roles. For instance, following the American superhero comics of the 80s, there emerged Fist of the North Star (1984) in Japan which features a disproportionally masculine warrior who masters a deadly martial art which gives him the ability to kill most adversaries through the use of the human body’s secret vital points, often resulting in an exceptionally violent and gory death. As Darling-Wolf (2001) observes, Japan’s Westernization hegemonized the definition of beauty and sexuality, which amounts not only a set of deeply patriarchal and racialized aesthetics and ethics of being. As scholars have written extensively, the adaptation of Western concepts entailed a crucial process of negotiation both during Japan’s early modernization period and under American occupation. The intense process of cultural (re)negotiation that followed Japan’s WWII defeat and paved its path to prosperity required a complete erasure—or at least reinterpretation—of the past and of Japan’s previous relationship to its former enemies.

The issue to appraise, therefore, is twofold. Not only should we point out—as many have done so—the tendency of whitewashing in Hollywood films, but also how and why Japanese artists “whitewashed” their characters in the first place. This is essentially a reflection on the cultural dynamics of the struggle for power and autonomy.

Kowloon Walled City: The Slum in Hong Kong that Inspired Ghost in The Shell

I am glad that I saw this film in Hong Kong, where the original manga took its inspiration and many of the scenes were shot (Kowloon Walled City especially). Similar to the Japanese history of being dominated by and aspiring to assimilate and compete with the West that is neglected by the makers and audience, Hong Kong is another vivid example of such underlying dynamics.

Originally a Chinese military fort, the Walled City became an enclave after the New Territories of Hong Kong were leased to Britain in 1898. Its population increased dramatically following the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong during World War II as refugees fled in. Demolished in 1992, now only a public park remains that remembers the extraordinary people who endured and transformed extraordinary times. Japanese researchers surveyed the place before the demolition. So intrigued by the Walled City, Japan later re-created it in an amusement park in Kawasaki—from its eerie, narrow corridors right down to the rubbish. Much of this inspired the background setting of Ghost In The Shell.

In addition to the Kowloon Walled City, Hong Kong also has the futuristic character perfect for science fiction: There are twice as many skyscrapers (buildings of at least 14 stories) in Hong Kong, when compared to its nearest rival city, New York. With the world’s greatest number of skyscrapers in one city, Hong Kong’s urban landscape has a way of overpowering visitors. At the same time, there are 400,000 households living under the poverty line, which is set at $14,300 Hong Kong dollars (US$1,800) for a house of four. A survey published in early 2014 by Demographia International Housing Affordability revealed that Hong Kong’s property market has become the world’s most expensive, with the median housing price reaching $4,024,000 Hong Kong dollars, or US$519,216. The hike in property prices signifies a thriving economy in Hong Kong. However, many local residents are excluded from the profits brought by global capitals. They struggle financially and often live in slums. This social divide, especially in terms of housing situations, inspired the original background setting in the manga version of Ghost in The Shell, as the wealthy enhanced live above and the poor humans live in slums.

Such social divide in Hong Kong is, to a large extent, a result of its “programmed” function as the utopia land for imperial trades and global capitalism. The Crown Colony of Hong Kong was a product of the first Anglo-Chinese War (or more famously known as the Opium War 1839-42). As Steve Tsang notes, behind this war was the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the early global capitalism through British and British Indian trade with China. From the very beginning, the British intended to build in Hong Kong not a settlement colony but an imperial outpost for the promotion of trade and economic exchanges with the Chinese Empire, and they expected to enjoy the lion’s share of the benefits by virtue of their unrivalled economic and commercial might. Hong Kong quickly became a base to support the trade operations of the British Empire across the globe.

At the same time, British jurisdiction provided stability, security and the predictability of British law and government, enabling Hong Kong to flourish as a center for international trade over Shanghai, as mainland China gradually fell into wars and domestic upheavals. The rule of law has also become a focal point for the disputes and conflicts between mainland China and Hong Kong in recent years, most evidently manifested in the Occupy Central movement in 2014 (alternatively known as the Umbrella Movement, as some protesters used yellow umbrellas to defend against the use of pepper spray by police).

This movement was an unprecedented civil disobedience in Hong Kong history. The protestors petitioned the Hong Kong government and the central government in Beijing for full implementation of universal suffrage as indicated in the Hong Kong Basic Law Article 45, which delineates the requirements for electing the Chief Executive. After Hong Kong was handed over to China in 1997, according to the lease signed a hundred years ago, the elected legislature was abolished, and a Beijing-appointed body of lawmakers took its place. The intensified political struggle led to street actions, as reportedly over 30,000 protestors blocked roads and paralyzed the city’s financial district, if the Beijing and local governments did not agree to implement universal suffrage for the 2017 chief executive election and the 2020 Legislative Council elections according to “international standards.” However, the petitions and the protest were intentionally neglected by Beijing. The fragmented information and mutual misunderstandings also led to the accumulating conflicts among ordinary mainlanders and HongKongers, marking an increased ideological disparity.

For the protesters, the basic law in Hong Kong stands for the necessary condition of cosmopolitanism, democratic freedom, and universal values, versus the authoritarian ruling, which is, for many, represented by the Communist government. In March 2017, nine leaders and key participants of Hong Kong’s Occupy movement were arrested and charged for their roles in the 2014 pro-democracy street protests – a day after the new pro-Beijing chief executive took oath. The participants are facing charges of conspiracy to cause public nuisance, inciting others to cause public nuisance, and inciting people to incite others to cause public nuisance, marking the first such punishment meted out by Hong Kong’s justice system against those who brought chaos to the city in the name of democracy. At the same time, two mainland Chinese activists who supported pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong were also jailed for subverting state power. Many worry that it’s a sign of the end of the rule of law in Hong Kong. Although for visitors and expats who enjoy the food, the financial benefits, and the landscape in Hong Kong would rarely notice the changes that have been taking place.

The case of Hong Kong was as part of the global Occupy movements that emerged in recent years, and it proved to be the longest occupation of all. However, it did not receive enough media or scholarly attention, especially not from the RS community. I was very touched that my friend Paul F. Tremlett wrote an insightful article on Hong Kong’s Occupy Central movement, in which he observed the state capitalism as part of the Communist regime, along with the conventional representation of Hong Kong as a politically indifferent, capitalist utopia, that this protest was set to challenge. As a result, the financial space under an HSBC building as the old sacred order that was erupted. This is among the very rare international attention—including academic studies—dedicated to the situation in Hong Kong, a place that is often taken to be an apolitical capitalist utopia efficiently but quietly serving global economy. And much to Hong Kong’s dismay, this movement did not receive enough attention from the international world like the Arab Spring, in particular not from Britain, Hong Kong’s former ruler.

In this way, Hong Kong is the perfect metaphor for Ghost in The Shell’s apocalyptic setting, as it is in many ways abandoned by the imperial capitalist order that “programmed” it to be the Capitalist Utopia, and it is not getting nearly enough international exposure and attention while it has been struggling to hold the values and orders that it perceives as universal. Global capitalism contributed to the wealth that was accumulated on this island, and in the shadow of the global wealth lays the ghetto that is as dark as in Ghost in The Shell.

To summarize, the original manga as well as the Hollywood interpretation of Ghost in The Shell contain an abundance of information that demands our attention and reflection. And I have, accordingly, attempted to argue that this film tells the story of two societies that have contributed so much to the world’s economy and culture, but the history of how they emerged as part of the global capital is often overlooked or taken for granted. Even for intellectuals, unless they specialize in Asian Studies, the knowledge and information of these two places are often fragmented. Popular culture of course reproduces and reflects social realities, and it is the task of intellectuals to re-evaluate and scrutinize such reproductions with cultural awareness and systematic understanding in our increasingly cocooned world in the age of globalization.

Ting can be reached at @tingguowrites and https://ting902.com/.

Am still trying to relate this ‘Ghost in the Shell’ with religiosity..