Back in December 2014 I received an unexpected email from Switzerland:

Back in December 2014 I received an unexpected email from Switzerland:

We would like to invite you to a master class with PhD candidates and Post-Docs in 2015. These master classes are a main element of our program: For two or three days, we would like to discuss your work, approaches to the study of religion and give the participants the chance to discuss their projects with you.

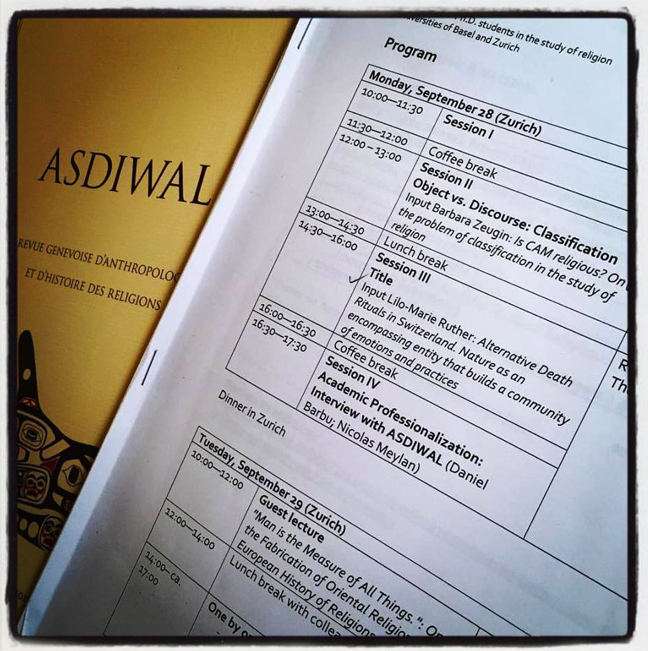

I agreed and am just back from three intensive days working with about 10 Swiss doctoral students in Religionswissenschaft — doing their studies at universities in Zurich, Basel, and Bern; I spent a couple nights in Zurich, working with students for two days (during which I also presented a public lecture written for the occasion — that’s it, above, outside my hotel in Zurich), had the good fortune to be interviewed while there for a future issue of Asdiwal (a Swiss annual journal in our field), and then took the train an hour east to Basel, where we all had a full day there as well. While some of the sessions were led by the students themselves, in which they presented a summary of their dissertation topics and after which we all had a chance to comment and ask questions about their work, other sessions were a series of one-on-one appointments some of the students decided to make with me, in which I camped out in a seminar room and, one after another, they’d come by and we would talk about their work for up to an hour each.

All the while sipping small cups of good coffee.

While I can’t speak for the students, of course, from my point of view it was a wonderful few days — but not just because of the coffee and fine Fall weather.

What I found so interesting was the ease with which many assumed that organizing the world by means of the category religion, or the category world religions, was itself a curious thing in need of some further study and scrutiny. In other words, they all seemed to agree that classification matters — better put, that studying how groups arrange and name their worlds tells us much about how people manage social life and give it the impression of purpose, meaning, and direction.

For example, some were interested in how certain types of end-of-life practice in a Swiss palliative care facilities was or was not classified as religious or spiritual (would the government fund it if it was called this or that?) or in how ritual entrepreneurs are now offering non-religious but spiritual funeral options in Switzerland and Germany, while others were curious about how criticisms of Islam are often smuggled within larger critiques of religion per se or in how narratives about breaks with the past are themselves ways of creating a sense of time and a sense of place in the here and now (i.e., the narrative about the break actually creates the impression of a break!). A common concern was both a narrative of contact and contest — e.g., how did locals in West Africa perceive the rules and expectations of the newly arrival colonials? — and a narrative of religious decline in Europe — e.g., what are people now doing with empty churches across Europe? Selling them? Tearing them down? Or trying to re-purpose them in ways that, on the surface at least, seem related to how they once might have functioned (but now in a seemingly more neutral, cultural way). From rational choice theory and network theory to the study of Russian Orientalism, it was also apparent that “theory” is not a dirty word in Switzerland; or, to rephrase: sure, people dance as part of religious ceremonies, and, afterward or when asked, they may even talk about what it means to them, but does documenting all this, no matter how faithfully or in what detail, exhaust what it is that a scholar of religion does when studying what people say and do?

Clearly, the answer I heard in Switzerland was no.

Which I found rather encouraging.

So my thanks goes not only to Prof. Christoph Uehlinger, in whose class I offered my public lecture (and who I had the good fortune to meet ten years ago when first lecturing in Zurich), and to the Basel team, notably Dr. Anja Kirsch, who coordinated the whole event, ushered me around from place to place, and made sure that the waiters understood what I was asking for, but also to all of the students (all of whom were at very different phases of their studies, from just beginning to just about to defend) who took daily trains to attend and who tolerated my many stories (“Well, I’ve got a story about that…”).

I’m looking forward to hearing how your work develops.