By Andie Alexander

Andie Alexander earned her B.A. in Religious Studies and History in 2012. She is now working on her M.A. in Religious Studies at CU Boulder. Andie also works as the online Curator for the Culture on the Edge blog.

Many of you may be following, or at least aware of, Rowan, KY county clerk Kim Davis denying marriage licenses to same-sex couples despite the recent Supreme Court ruling (on June 26, 2015) that legalized same-sex marriage across the United States. In the days following Davis’s refusal to cooperate, I have seen a lot of “bad religion” claims being made on social media and news media sites — i.e., claims by some that she exhibits an improper or inauthentically religious position. It has also since come out in the press that Davis has been married four times and had an affair with one man whom she eventually married. So what strikes me as interesting are the types of reactions and articles I have seen while scrolling through Facebook, seeking to invalidate her: she’s a hypocrite, she’s playing fast and loose with the Bible, her “personal beliefs” are infringing on others’, as a divorcée and adulterer she has no moral high ground — the list goes on.

Moving away from these apparent slut-shaming ad hominen attacks being made on Davis, I am more intrigued by the conversations regarding Davis’s personal beliefs (or, what one might call private) in opposition to state legal ruling (or public). This notion of the public/private domains is not new, but perhaps it is a little too taken-for-granted, in such cases, as a self-evident identifier for this (idea, belief, practice) or that. So I wonder how easily this distinction is defined in practice and what sort of work it’s doing.

For if we shift our attention away from whether we agree with what she reportedly believes and, instead, look more to this notion of examining how private, interior beliefs that are somehow set apart in distinction from some notion of a public space, then we can start to see certain types of social structures at play.

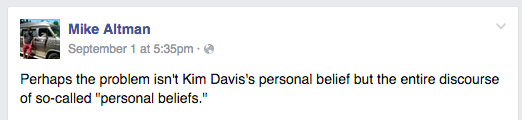

As Michael Altman aptly states, the issue is not whether what she believes is is right or wrong, but is instead this discourse on “personal beliefs.” Now one may think that her beliefs are extraordinarily problematic, in that they directly infringe on the rights of others. But whether one agrees or disagrees with Davis is, I think, to miss the point entirely. For anyone reading this post is bound to disagree with another in some regard. But when is it deemed okay to hold that someone’s beliefs are an example of “bad religion” as opposed to… good religion? I’m guessing that when the “belief” aligns with what the State, or some dominant social group, has sanctioned as acceptable — or at least, doesn’t actively go against that position — it’s judged okay, or perhaps innocuous, in the public or legal arena, but once that “belief” moves outside of the realm of “acceptable” it then becomes a “bad” belief.

As Michael Altman aptly states, the issue is not whether what she believes is is right or wrong, but is instead this discourse on “personal beliefs.” Now one may think that her beliefs are extraordinarily problematic, in that they directly infringe on the rights of others. But whether one agrees or disagrees with Davis is, I think, to miss the point entirely. For anyone reading this post is bound to disagree with another in some regard. But when is it deemed okay to hold that someone’s beliefs are an example of “bad religion” as opposed to… good religion? I’m guessing that when the “belief” aligns with what the State, or some dominant social group, has sanctioned as acceptable — or at least, doesn’t actively go against that position — it’s judged okay, or perhaps innocuous, in the public or legal arena, but once that “belief” moves outside of the realm of “acceptable” it then becomes a “bad” belief.

Thinking back to these notions of public and private spaces, let’s, for a moment, consider how this works. The distinction of public and private seems almost all too obvious until we stop to think about how private became private in the first place. At some point or another, someone had to draw that line to say what was once public and exterior is now private and interior, or vice versa.

For example, consider the Patriot Act (October 25, 2001) which significantly increased the government’s ability to conduct surveillance of citizens in the United States regarding any potential terror threat. What was once considered to be private information, practices, etc. of US citizens, free from government observation, then became public information supposedly used to counter potential terrorist actions. While that information was always readily accessible to the government, it was sanctioned as “private” until supposed need arose to make that information available to the State (or “public”) for national security measures. That is to say that the notion of private beliefs, information, practices, etc. are no more private than any other, but are deemed as such until it runs counter to the interests of the dominant social group, or in this case, the governing body of the State.

So instead of getting caught in the cross-fire of whether that is good or bad, we should examine who has that say and how it is regulated. For the private space to exist, it must be officially sanctioned and maintained as such — at least until it’s changed again. As Russell McCutcheon argues,

The mistake many make… is thinking that the institution that governs the public is called government or the State, and that it is in some sort of competition with, or opposition to, the institutions that exist in the private realm (like churches, synagogues, mosques, bowling leagues, etc.)… It’s a mistake because the State is, instead, on both sides of the public/private distinction, constituting its operating system, inasmuch as it is the overarching body that sets and polices the limit between the two (doing so in a way conducive to the interests of those comprising the State, of course)…

If one follows this line of thinking, then we can see how the so-called private (or “personal beliefs”) is just as much bound by these external constraints as anything else. While one may disagree and exercise different beliefs from, say, the State, they still must act in accordance with these restrictions. Dissent, therefore, is allowed so long as it does not antagonize the interests of the State. Once that happens, the individual or group that is dissenting is quickly checked by that governing body, with a varying degree of severity. So if we look at the thing we call religious freedom, or freedom of belief, in this light, we can see how closely tied it is to the State’s interests, despite the commonly held notion that it is free to work in opposition to the State.

Applying this to ideas of judgments concerning something amounting to “bad religion,” we can begin to take a somewhat different approach. Instead of seeing these many accusations of hypocrisy and disregard of what Bible supposedly really means as solely “holier than thou” arguments or as promoting the more “authentic” religion — which they certainly are in some ways — we can begin to see them as an attempt, on the part of other social actors, working in accordance with legal ruling, to manage dissent (e.g., Kim Davis’s actions and interests) within the State itself. This language — bad vs. good religion — is used to undermine and delegitimize the dissenting faction, thereby promoting certain personal beliefs (or private) over others in the public arena, and further blurring the lines of this public/private distinction.

As long as the “private” is deemed acceptable by the dominant social group — or in this case, the State –, then the promotion of those ideas or beliefs, in public and through legal action, over others is not challenged, as they align with the position of the State. So rather than seeing these beliefs, etc., as private and interior notions that are then expressed, we can instead see them as publicly accepted and reified external notions that we then internalize as our own to subsequently promote as personal, private beliefs.

But don’t get me wrong, I’m not criticizing the State in any way, nor am I defending Davis’s actions; rather, I am trying to draw attention to how social groups are maintained in such a way that it is seemingly natural, by letting the group (or, public) appear to be determined by the freely believing individual (or, private).

Nice one, Andie! And timely, too. Another piece of the puzzle is to keep in view the ways states themselves are seldom coherent, frequently fractured internally, with various appendages working at counter-pruposes. Alas, I suppose that is what “checks and balances” are meant to be about… In Hawaii right now we have a vivid example of the many limbs and organs of the state being markedly out of synch. On Mauna Kea, the state is implicated in some way at every level–from land leases for the telescopes to funding for the legal defense teams supporting the protestors. Whoa. And religion is announced and performed (affirmatively or dismissively) at just about all of these levels, and especially in their intersection. In terms of public/private, so many Hawaiians are employed by some branch of the government that the distinction is at once “good to think” and hard to track.

Thanks so much for the feedback, Greg! I had not realized that about what has been happening on Mauna Kea and how closely it is tied to these issues. I definitely agree with you on the complexity of the “state”. I suppose I was thinking, at least in this sense, of the legal state that has the power to draw these distinctions and to fall on the “wrong” side results in quick action to counter it. But looking more into notions of what comprises the state, how they too are constantly bumping up against one another, would be an interesting direction to go in, I think, because there is just as much tension in how issues play out there. More to think on! Thanks!