In 2001, in a collection of essays, I included a chapter on teaching courses on theories of myth and ritual, describing there how I sometimes use pop music (songs that, with each year, get more and more dated) to make a point.

In 2001, in a collection of essays, I included a chapter on teaching courses on theories of myth and ritual, describing there how I sometimes use pop music (songs that, with each year, get more and more dated) to make a point.

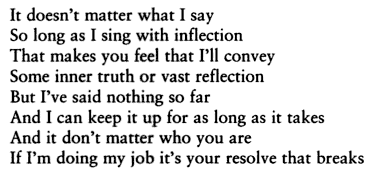

For example, after citing the lyrics to “Hook” (something I blogged about on this site a year ago):

I’ve used it to illustrate the late Frits Staal‘s work on the meaninglessness of ritual, writing as follows (see p. 210 of Critics Not Caretakers):

I’ve used it to illustrate the late Frits Staal‘s work on the meaninglessness of ritual, writing as follows (see p. 210 of Critics Not Caretakers):

I’ve written a little about some of the other songs I periodically use to complicate how students see meaning-making — one example is John Mellencamp’s 1983 hit “Little Pink Houses,” which I discussed in the introduction to The Discipline of Religion (2003: 21). But now, through the magic of embedded videos, the point I tried to make then can be illustrated a little better.

I’ve written a little about some of the other songs I periodically use to complicate how students see meaning-making — one example is John Mellencamp’s 1983 hit “Little Pink Houses,” which I discussed in the introduction to The Discipline of Religion (2003: 21). But now, through the magic of embedded videos, the point I tried to make then can be illustrated a little better.

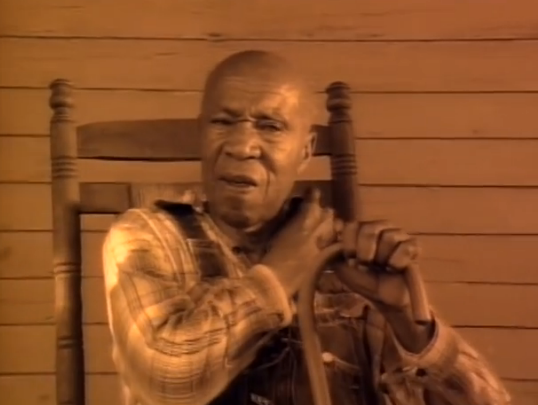

If you don’t know this once popular song, watch the video and consider the lyrics:

While I’m not interested in what the song really means, at the level of lyrics it seems tough to read it as anything but a critique of the common American dream rhetoric; for I don’t think we come away agreeing that the black man with “the interstate runnin’ through his front yard,” the greasy kid with the greasy smile who realizes he’ll never amount to much, or that the lady whose partner remembers when she used to be pretty have all got it very good.

None of us probably want to swap places with them.

“Ain’t that America…” therefore sounds more like a sarcastic lament than a patriotic anthem.

But who listens to the verses’ lyrics? Especially when you’ve got a great chorus and a video of classic Americana images?

One of which happens to be a drug-dealing motorcyclist in a trailer park, by the way.

One of which happens to be a drug-dealing motorcyclist in a trailer park, by the way.

But who really “sees” that and who “hears” the song as critique? Probably not many — if you know the song I’d wager you’ve never heard it this way.

But who really “sees” that and who “hears” the song as critique? Probably not many — if you know the song I’d wager you’ve never heard it this way.

The point? Form determines content.

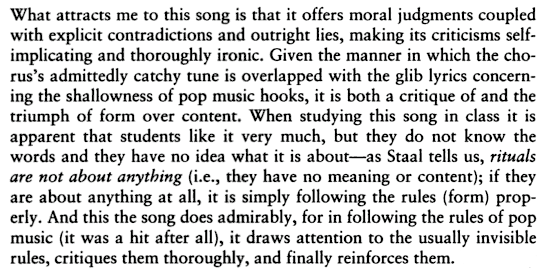

But, as I argued in 2003, an even better illustration of this general principle — of how contingent context creates meaning, which means that meaning is a flexible historical and social product — was seeing this song performed as part of the Concert for New York City, coming just weeks after the attacks on 9-11.

For now a song that, taking your cue only from the verses’ lyrics, could easily be read as a critique of the the American dream was being sung as a tribute to the first responders who so tragically died that day in their efforts to help the victims in the towers.

For now a song that, taking your cue only from the verses’ lyrics, could easily be read as a critique of the the American dream was being sung as a tribute to the first responders who so tragically died that day in their efforts to help the victims in the towers.

Suddenly, “Ain’t that America…” has no irony to it whatsoever.

The distance between the setting and the emotion of this 2001 performance, on the one hand, and just reading the lyrics, on the other, without any knowledge of the chorus’s hook, is, at least to me, quite provocative; over the years, I’ve quite effectively used this song and this performance to press students to mull over how it is that we, as situated human actors, make our worlds habitable and the things in them meaningful — and how different settings and different sets of interests make it possible to see things rather differently.

That pop music illustrates all this so nicely is, to me, an added benefit — especially in a field where so many seem to think that our data is somehow obviously set apart and naturally, deeply significant.

Oh, and one more thing: given the effort that some people in the US now seem to be putting into framing the attack that killed 9 African-American church-goers a couple days ago in a way that ensures that we don’t end up talking about race (such as seeing it as an attack on Christianity or an opportunity to advocate for arming the population) well, the admittedly dated analysis above (I was publishing on this in 2001 and 2003, after all) seems pretty relevant still. For the interesting question still concerns the practical conditions that need to be in place in order to read something as we do.

So, rather than contesting over what the tragic event in Charleston ought to mean, maybe we, as scholars, should instead inquire what needs to be in place for some to see it in a way that makes no reference to a white shooter and nine black victims. For if we’re interested in understanding the difference in readings then we need to look more closely not at the event being interpreted but, rather, at the setting and the interests of its many interpreters.

After all, we’ll better understand Mellencamp’s man on the porch not by looking at his house more closely, and debating its merits, but by figuring out why, despite having an interstate in his front yard, he (both the verse’s character and, more importantly perhaps, the songwriter who created him) thinks he’s got it so good.

song / lyrics does have its own power for listeners