Liz Long is a junior from Colorado who is double-majoring in Psychology and Religious Studies. She is interested in the effects of religion and culture on behavior. This post was originally written for Dr. Rollens’ course,

REL 360: Popular Culture/Public Humanities.

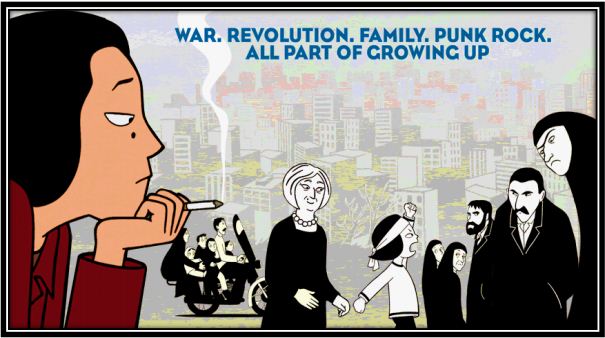

Persepolis, a film based on Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novel of the same name, looks at a number of oft-discussed issues in the study of Islam. Though the story takes place post-Iranian revolution, many of the problems Marjane faces are not contained to this time frame, people, or culture. Of particular interest is the portrayal of women, not just in Iran, but also during Marjane’s time in Europe. Islam is frequently portrayed as inherently oppressive to women, especially in contrast with Christianity. However, the film demonstrates that while parts of the Iranian regime restrict women’s rights and freedoms, the negative attitude towards women and their sexuality is essentially the same across cultures.

The most obvious example of this similarity is in discussions of Marjane’s sexuality. In Vienna, as Marjane is leaving to meet her boyfriend, she overhears the woman she’s staying with tell a friend on the phone that she thinks Marjane is a prostitute. later, after Marjane’s return to Iran, she sits as a long line of friends and family ask her about her time in Europe. Her friends ask if she had sex with a man. She says yes, and her friends are enthralled–until she mentions that she’s had sex with more than one man. Suddenly, her friends’ reactions change from fascination to disgust. their reactions show that one is fine, but more than that and suddenly she’s disgusting. It doesn’t seem to matter where she is–the idea of an unmarried, sexually-active young woman seems to be morally reprehensible to members of both cultures. It isn’t confined to one specific culture or religion.

Later in the film, Marjane stands up to the administration at her university in Iran. They have announced that the women’s clothing is too distracting, and changes will be made to the dress code–despite the fact that they all must already wear headscarves and full cloaks. Here, Marjane points out the hypocrisy in the reforms. The men at her school do not have any sort of recognizable dress code, and don’t have to cover their heads or wear full, loose cloaks, but the women’s full body coverings have become too distracting. Yet somehow, the women are able to get along without any major distractions due to the men’s skin and hair. Marjane also points out that as an art student, the new clothing restricts her (already restricted) range of motion, and makes it more difficult for her to get her work done.

Again, this argument does not appear in Muslim-majority cultures alone. In an article published last December in the online magazine Everyday Feminism, Ellen Friedrichs argues that:

[A] common argument for monitoring girls’ clothes is that boys can’t focus on school when they encounter exposed female skin or see curves. Not only is this view utterly heterosexist, but it also reduces boys to slathering sex fiends with no self-control and then tells girls they are responsible for those boys’ behavior–which is disparaging to all parties.”

The pervasive idea that sexism and oppression of women is a “Muslim problem,” rather than a global problem, pushes the onus of change away from us, and onto the other. By saying that we Christian Americans (and Europeans in many cases) don’t have the same problem, we demonize Islam. This allows us to more easily pass off Islam and Muslim-majority cultures as the enemy and legitimizes our military presence in these countries. We say that we must democratize and Christianize these other countries because without us, the women would be oppressed. But we fail to take into account that many of the same policies and attitudes are present in our own society as well. When we categorize Islam and Muslims this way, we can ignore the problems in our own culture by pointing out the flaws in another. Persepolis shows that though the government’s involvement in (and the public’s attitudes towards) these issues may differ by country, the general problem remains the same no matter where you go.