Season 4 episode 15 of the TV show Futurama, entitled “The Farnsworth Parabox,” has a great illustration of a principle that Sigmund Freud called the narcissism of minor differences.

Season 4 episode 15 of the TV show Futurama, entitled “The Farnsworth Parabox,” has a great illustration of a principle that Sigmund Freud called the narcissism of minor differences.

Prof. Farnsworth, it turns out, created a parallel universe, in a box (yellow in one world, blue in another), and, instead of destroying it, everyone from both worlds ends up in the same place, of course. And, unlike the parallel Farnsworth’s assumption that people in parallel universes are up to no good —

Prof. Farnsworth, it turns out, created a parallel universe, in a box (yellow in one world, blue in another), and, instead of destroying it, everyone from both worlds ends up in the same place, of course. And, unlike the parallel Farnsworth’s assumption that people in parallel universes are up to no good —

And when you create a parallel universe, it’s almost always populated by evil twins.

— it turns out they’re all pretty much the same, apart from having different hair color. Oh, and all the coin flips (by which they seem to make all the momentous decisions in their lives) result in different outcomes.

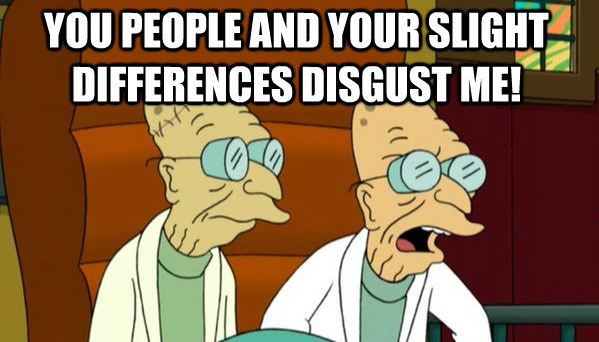

Frustrated early on, the Professor from the one universe exclaims:

Frustrated early on, the Professor from the one universe exclaims:

You people and your slight differences disgust me. I’m going home. Where’s that blue box with our universe in it?

And there we have a pretty effective illustration of a basic social principle that Freud discussed in, among other places, his 1930 book, Civilization and its Discontents:

As a Canadian, living and working in the US for my whole career, I see myself reflected in this; for I seem to naturally see rather consequential differences between these two places — from significantly different politics and varying social welfare programs to rather different views on gun laws and the need to finish sentences with “eh?” (let alone apparently saying “a-boot” instead of “a-bout”); but, long ago, I recall speaking, after class one day, to a foreign student from South Korea, as I recall, back when I worked at another US school. We shared something in common, of course, given our familiarity with the various immigration statuses and rules, but it soon became apparent to me that our affinity pretty much ended there for, having myself come from a country that largely speaks the same language as here, eats much the same food, watches much the same television and movies, wears the same clothes, and was initially colonized and then populated from pretty much the same waves of European migration, it seemed rather insincere to presume that my experience as an emigrant was similar enough to that student’s that we could both share the same sense of difference from the US culture that surrounded us.

As a Canadian, living and working in the US for my whole career, I see myself reflected in this; for I seem to naturally see rather consequential differences between these two places — from significantly different politics and varying social welfare programs to rather different views on gun laws and the need to finish sentences with “eh?” (let alone apparently saying “a-boot” instead of “a-bout”); but, long ago, I recall speaking, after class one day, to a foreign student from South Korea, as I recall, back when I worked at another US school. We shared something in common, of course, given our familiarity with the various immigration statuses and rules, but it soon became apparent to me that our affinity pretty much ended there for, having myself come from a country that largely speaks the same language as here, eats much the same food, watches much the same television and movies, wears the same clothes, and was initially colonized and then populated from pretty much the same waves of European migration, it seemed rather insincere to presume that my experience as an emigrant was similar enough to that student’s that we could both share the same sense of difference from the US culture that surrounded us.

Or, to rephrase, focusing on those now slight gaps in the identity that Canadians and Americans share quickly looked rather different when seen from the perspective of someone for whom those differences were pretty much inconsequential and thus unrecognizable — like when I’m sometimes traveling overseas and locals mistake me for being British (simply because I speak English, I guess). The things that distinguish me from a Brit are huge in number, at least from my point of view, but pretty much unseen for some others.

Small differences, once focused upon with great intensity, can seem of great consequence, forming the building blocks of social formation.

Dr. Seus’s story of the star-bellied and plain-bellied Sneetches fits here pretty well too, come to think of it.

And that’s the beauty of bringing social theory to your work; for if we’re trying to study basic techniques ordinary social actors use in virtually any moment of identification — like calling something “a religion” or “a ritual” — then why wouldn’t a cartoon be a good place to start talking about all this?

And that’s the beauty of bringing social theory to your work; for if we’re trying to study basic techniques ordinary social actors use in virtually any moment of identification — like calling something “a religion” or “a ritual” — then why wouldn’t a cartoon be a good place to start talking about all this?