Thanks to the wireless internet on campus and an enterprising student in class with a laptop, a quick e.g. turned into an even better example this semester.It was in my seminar on origins narratives, which looked at the way they have practical effect in the present (rather than just seeing them as being disinterested narrations of long past, authoritative events [see here for another post on this class]). Early in the semester I came to class prepared with a few easily digested examples to put before the students, one of which was the US dollar itself, complete with its portrait of George Washington — the much celebrated revolutionary war general and “founding father” who was also the nation’s first President.

Thanks to the wireless internet on campus and an enterprising student in class with a laptop, a quick e.g. turned into an even better example this semester.It was in my seminar on origins narratives, which looked at the way they have practical effect in the present (rather than just seeing them as being disinterested narrations of long past, authoritative events [see here for another post on this class]). Early in the semester I came to class prepared with a few easily digested examples to put before the students, one of which was the US dollar itself, complete with its portrait of George Washington — the much celebrated revolutionary war general and “founding father” who was also the nation’s first President.

If we know just a little about the role played by Parson Weems (d. 1825) in creating the morality tales that we tell about Washington even to this day, the dollar bill’s design and lack of major change in recent memory, starts to become a rather interesting example of how origins narratives that posit a smooth linkage between past and present allow us to create the impression of, shall we say, a land that time forgot — that land being the way we our own world works, of course. For the last thing we need, if we’re out to authorize how we think things work, is to see them as historical, contingent and thus changeable, maybe even arbitrary.

For now our tales of the past will have to take into account accident and coincidence….

But then the e.g. got out of my control — as happens, in my experience, with all good classes. For the students started commenting in ways I hadn’t anticipated, asking questions of their own, and getting curious about all sorts of things. And then it happened: one of them, silently working on his laptop while we talked, had discovered something: how much it costs to manufacture a dollar bill.

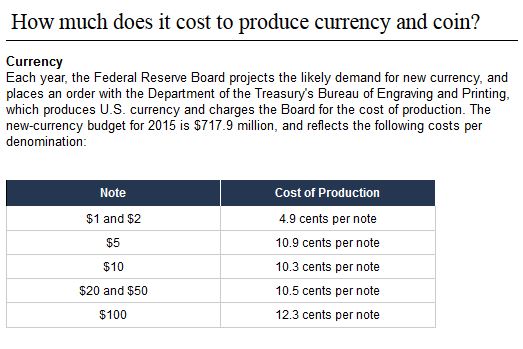

For, according to the US’s Federal Reserve (click the graphic to visit their page)…

Suddenly, the e.g. of the dollar bill with Washington’s face on it got a lot more interesting, for not only the difference between a past to which we can’t time travel, on the one hand, and, on the other, modern stories we tell about it was not the only gap into which we could inject the role played by origins imagery, in hopes that they’d help us to paper over the uncharted distance between; for now a myth of origins was equally wrapped up with a 95.1¢ gap, in the here and now, between what it costs the government to make a dollar bill and how long we have to work to make a dollar.

Suddenly, the e.g. of the dollar bill with Washington’s face on it got a lot more interesting, for not only the difference between a past to which we can’t time travel, on the one hand, and, on the other, modern stories we tell about it was not the only gap into which we could inject the role played by origins imagery, in hopes that they’d help us to paper over the uncharted distance between; for now a myth of origins was equally wrapped up with a 95.1¢ gap, in the here and now, between what it costs the government to make a dollar bill and how long we have to work to make a dollar.

What was interesting is that few of the students had ever thought of this gap before — I’m not saying it rocked their worlds, but we had to pause, mull this over, discuss the consequences of this new knowledge, and do a little thinking on how seemingly timeless identities, such as value, are created in our minds and why we think that those small pieces of 75% cotton and 25% linen blend carry a value far more than they’re actually worth.

All this was thanks to a unscheduled detour in class. So while it may be, at times, a distraction — and that’s one of the reasons I ensure these seminar students also had notebooks for class (which they turned in to me near the end of the term), in which they took handwritten notes in class, summarized readings, and, most importantly, provided evidence of thinking about class after it’s over — this moment was directly the result of technology in the classroom.