I heard a book review on the local radio station this morning, focusing on the famous US biologist (specializing in the study of ants) E. O. Wilson’s latest views on, among other things, religion.

I heard a book review on the local radio station this morning, focusing on the famous US biologist (specializing in the study of ants) E. O. Wilson’s latest views on, among other things, religion.

And a thought occurred to me: nobody would listen to me if I started talking about ants, would they? And if they did pay attention they’d likely hear what I was saying as mere truisms, repetition of common sense — “Look, they’re tiny and oh, how they scurry about…” — claims hardly heard as making a contribution to the science of mymecology.

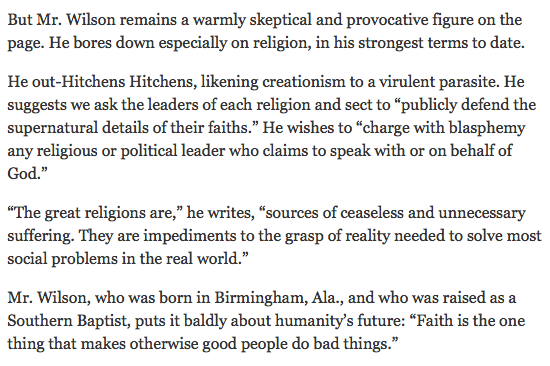

Yet people trained in a host of other fields seem to have no difficulty making authoritative statement about what religion is or what it does, statements which others read as anything but mundane folk knowledge. After all, no less a source than the New York Times saw fit to review Wilson’s new book, The Meaning of Human Existence):

Which means that our work, as trained specialists in the study of religion, is likely understood by others as being not much different from what they are already doing themselves — talking about the world by using the term “religion,” taking stands on whether it is good or bad, to be protected or eradicated. And so it’s no wonder that students who attend our courses often seem to walk in the door already feeling like they’re experts on the subject matter.

Which means that our work, as trained specialists in the study of religion, is likely understood by others as being not much different from what they are already doing themselves — talking about the world by using the term “religion,” taking stands on whether it is good or bad, to be protected or eradicated. And so it’s no wonder that students who attend our courses often seem to walk in the door already feeling like they’re experts on the subject matter.

That’s why they’re often sadly surprised to find the courses hardly easy, as they had hoped.

Given this widespread presumption that confidently-stated folk knowledge on this one topic constitutes expertise, scholars of religion probably seem to many people to be little more than a professorial version of Captain Obvious — a presumption that constitutes the first hill an instructor has to climb at the start of each new semester: to begin to persuade students that their own experience talking about the world is in fact their primary object of study.

The trick, then, is for students to come to see not just writers like Wilson but to see themselves as well as native informants — articulate and well educated, yes, but native informants nonetheless, people whose statements make a particular sort of world possible to conceive and move within. If scholars of religion are doing something other than repeating truisms about their subject matter (and yes, many do little more than that, if you ask me, and that doesn’t help the profession much) then it will likely involve them in studying how some of us happen to use the category religion (much as we use the categories nation, gender, race, etc.) to create and manage the conditions in which we can come to say we are or are not like someone else. What’s more, such scholars will then write books rather different from Wilson’s latest — The Way We Make Existence Meaningful would be a title in keeping with the model of expertise that I have in mind.

Climbing that hill is no easy exercise, of course, which is among the reasons that the introductory course is probably the most important class that we teach; for it sets the table for skills of importance throughout the entire degree: the skill of being curious about what you yourself take for granted.