Having just come from the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, where scholars of religions’ input on the topic of climate change was encouraged, inasmuch as we are presumed to have some special expertise based on what we happen to study — as phrased in a memo sent last year to the chairs of its various program units, written by our then incoming President:

Having just come from the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, where scholars of religions’ input on the topic of climate change was encouraged, inasmuch as we are presumed to have some special expertise based on what we happen to study — as phrased in a memo sent last year to the chairs of its various program units, written by our then incoming President:

It is our scholarly duty, I would argue, that we bring forward a scholarship from a wide set of traditions that may suggest a meaningful set of actions in response to an unprecedented and shared crisis…

— and at which, in my reply to a session on interreligious dialogue, I once again critiqued a statement from 1997 in which Jacob Neusner argued that the:

special promise of the academic study of religion is to nurture this country’s resources for tolerance for difference, our capacity to learn from each other, and to respect each other…

I find it interesting to turn attention to the manner in which scholars of religion apply their work to domains outside those of their expertise.

For all too often I find that presumptions about the special nature of what we study lead to overly confident presumptions of the scholar’s special relevance in commenting on current events. After all, if religion is understood as unique, deep, pan-human, transcendent, and thus motivating almost everything we do, then why wouldn’t we have something to say about virtually anything in the news? For if, of the more than 150 program units, our professional organization has this many subgroups devoted just to study “Religion and…” or “Religion in…” topics:

Religion and Cities Group

Religion and Disability Studies Group

Religion and Ecology Group

Religion and Ecology Group and Scriptural/Contextual Ethics Group

Religion and Ecology Group, Science, Technology, and Religion Group, and Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science

Religion and Food Group

Religion and Food Group and Religion and Migration Group

Religion and Humanism Group

Religion and Migration Group

Religion and Politics Section

Religion and Popular Culture Group

Religion and Popular Culture Group, Religion, Film, and Visual Culture Group, and Religion, Media, and Culture Group

Religion and Public Schools: International Perspectives Group

Religion and Science Fiction Group

Religion and Science Fiction Group and Religion, Film, and Visual Cultures Group

Religion and Sexuality Group

Religion and Sexuality Group and Religion, Colonialism, and Postcolonialism Group

Religion and South Asia Section and Jain Studies Group

Religion and the Literary in Tibet Seminar

Religion and the Social Sciences Section

Religion and the Social Sciences Section and Psychology, Culture, and Religion Group

Religion and the Social Sciences Section and Religion and Cities Group

Religion and the Social Sciences Section, Religious Conversions Group, Secularism and Secularity Group, and Sociology of Religion Group

Religion and US Empire Seminar

Religions in Chinese and Indian Cultures: A Comparative Perspective Group

Religion in Europe and the Mediterranean World, 500-1650 CE Group

Religion in Europe Group

Religion in Europe Group and Secularism and Secularity Group

Religion in Latin America and the Caribbean Group

Religion in South Asia Section

Religion in South Asia Section and Jain Studies Group

Religion in South Asia Section and Sikh Studies Group

Religion in South Asia Section and Study of Islam Section and Hinduism Group and Jain Studies Group and Sikh Studies Group

Religion in Southeast Asia Group

Religion in the American West Group

…, well, then you know that scholars of religion are pretty confident that their work is endlessly relevant.

So when it comes to one particularly widely known news story in the U.S. media at the moment — the recently announced decision of a grand jury not to indict a white police officer who, this past summer, fatally shot an unarmed African American teenager on the street in Ferguson, MO — I found a post on Facebook this morning rather interesting. For it suggests that there are still those among us who understand that their work is relevant not because it is concerned with some deep aspect of “the human” but, instead, because human beings seem to have a relatively small set of techniques that we use in our ongoing acts of social/identity formation, suggesting that what we know from one situation can help us to understand another.

For example (quoted with her permission):

What I found so refreshing about this post is that, unlike Zoloth and Neusner (both of whom were quoted above), Reed makes plain that her expertise is relevant because an analogy can be posited, whereby studying the effects of certain forms of representation in one setting can shed light on issues of representation in another, both of which are far removed in time and space. Dropping the assumption that our object of study is special, this move suggests to me quite the opposite: that our object of study — people, what they say, do, and leave behind when they’re gone — is rather mundane and, because it is commonplace, whatever we happen to study might be but one instance of what are in fact culture-wide techniques and results.

What I found so refreshing about this post is that, unlike Zoloth and Neusner (both of whom were quoted above), Reed makes plain that her expertise is relevant because an analogy can be posited, whereby studying the effects of certain forms of representation in one setting can shed light on issues of representation in another, both of which are far removed in time and space. Dropping the assumption that our object of study is special, this move suggests to me quite the opposite: that our object of study — people, what they say, do, and leave behind when they’re gone — is rather mundane and, because it is commonplace, whatever we happen to study might be but one instance of what are in fact culture-wide techniques and results.

So although common, their uses are compelling nonetheless.

All of this suggests to me that our work, as scholars of religion, is very relevant to understanding all sorts of things, but not because we have special insights into a special aspect of the so-called human condition but, instead, because we’ve seen these things before, perhaps in all sorts of other places, and we therefore know something about how they work(ed) elsewhere — knowledge that might shed light on what they’re doing here and now.

Want another example?

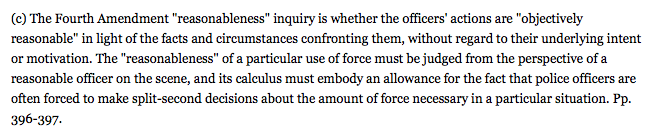

Consider the U.S. Supreme Court case that is so important to the grand jury’s decision not to charge Officer Darren Wilson in the case of Michael Brown’s shooting on Aug 9, 2014: Graham v. Connor 490 U.S. 386 (1989). As described in the opening to the judgment, that case concerned:

Petitioner Graham, a diabetic, asked his friend, Berry, to drive him to a convenience store to purchase orange juice to counteract the onset of an insulin reaction. Upon entering the store and seeing the number of people ahead of him, Graham hurried out and asked Berry to drive him to a friend’s house instead. Respondent Connor, a city police officer, became suspicious after seeing Graham hastily enter and leave the store, followed Berry’s car, and made an investigative stop, ordering the pair to wait while he found out what had happened in the store. Respondent backup police officers arrived on the scene, handcuffed Graham, and ignored or rebuffed attempts to explain and treat Graham’s condition. During the encounter, Graham sustained multiple injuries. He was released when Connor learned that nothing had happened in the store. Graham filed suit in the District Court under 42 U.S.C. 1983 against respondents, alleging that they had used excessive force in making the stop, in violation of “rights secured to him under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and 42 U.S.C. 1983.”

Among the items upheld by the court in finding that the use of force was not excessive in this case was the following:

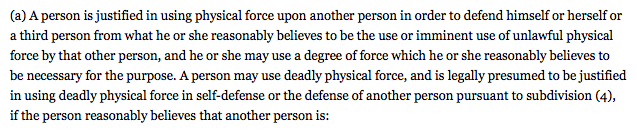

So, the key here — not unlike so-called “Stand Your Ground” laws throughout the U.S., such as Alabama‘s, which states:

So, the key here — not unlike so-called “Stand Your Ground” laws throughout the U.S., such as Alabama‘s, which states:

— is the person’s belief that they are in danger or that someone is about to endanger others, and not the actual fact of endangerment (i.e., the intentions or motivations of the one believed to be endangering others are not relevant at all). So it strikes me that scholars of religion trained in studying such things as discourses on belief and intentionality — that is, those who study how social actors use claims concerning such internal states and dispositions in what are actually public contests over place, rank, and identity — might have much to say about how U.S. or other laws rely upon this notion of “belief” (along with the work done by determining what does or doesn’t count as “reasonable” about these supposedly interior states.

— is the person’s belief that they are in danger or that someone is about to endanger others, and not the actual fact of endangerment (i.e., the intentions or motivations of the one believed to be endangering others are not relevant at all). So it strikes me that scholars of religion trained in studying such things as discourses on belief and intentionality — that is, those who study how social actors use claims concerning such internal states and dispositions in what are actually public contests over place, rank, and identity — might have much to say about how U.S. or other laws rely upon this notion of “belief” (along with the work done by determining what does or doesn’t count as “reasonable” about these supposedly interior states.

After all, people have all kinds of beliefs, but which will or won’t get them out of a possible grand jury indictment? For we know much about how one set of beliefs concerning invisible beings can be seen by a specific group as orthodox and safe while another is said to constitute a so-called radical cult. The question, of course, us who gets to set and apply the standards.

And, once again, the wide relevance of our work is not because of some special insight we have into the inner workings of the human heart but, instead, because, regardless the situation, social actors seem to have a relatively stable repertoire of techniques that they use to compete for advantage or just to try to establish a place to call their own — whether applied to property or their very person. And, working in the human sciences, I think we have something to say about all this.

So it would be nice to see more scholars of religion making contributions to what’s in the news…, but doing so from a far more humble position, recognizing the limits of our expertise but while also seeing all sorts of analogies and applications that might help explain the moment in which we now all find ourselves. For I’d argue that we all study the same thing: people, their contests, and what they leave behind once they’re gone.

Postscript

Want an example of what a scholar of religion might profitably say about all this? Then click the image below and see what hit the web as I was publishing this post, written by a colleague who once worked in our Department.