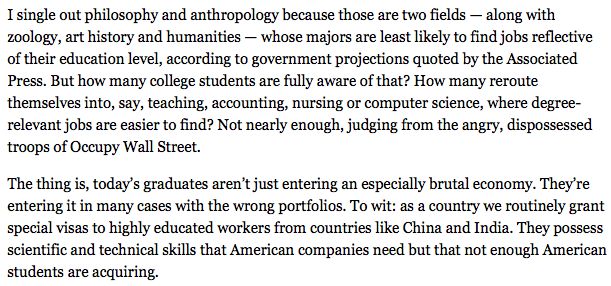

Back in April, 2012, Frank Bruni, a regular columnist for The New York Times Magazine, wrote an Op-ed piece that was much discussed at the time. Entitled “The Imperial Promise of College,” it argued that the condition of the current economy (e.g., the high un/under-employment rate, the staggering amount of collective student debt, etc.) should prompt college students to select majors that have direct, practical pay-off. After singling out a couple of examples of majors that, in all likelihood, turn out to be unrelated (or as he might have phrased it, irrelevant) to someone’s eventual career, he writes:

The subsequent letters to the editor about Bruni’s column strike me as far more interesting than the column itself, since the editorial opinion he expresses is hardly new (the Governor of Florida, Rick Scott, made much the same argument last Fall). In fact, you don’t even have to buy the newspaper to hear it, for I’d wager that most of my own Department’s undergraduate majors have heard it freely offered by someone in their family during some holiday meal.

The subsequent letters to the editor about Bruni’s column strike me as far more interesting than the column itself, since the editorial opinion he expresses is hardly new (the Governor of Florida, Rick Scott, made much the same argument last Fall). In fact, you don’t even have to buy the newspaper to hear it, for I’d wager that most of my own Department’s undergraduate majors have heard it freely offered by someone in their family during some holiday meal.

When students tell me about hearing this sort of comment on their choices–a curiously disempowering thing, really–and ask what I think, my reply has always been that, while some undergraduate training prepares them for a very specific career, others provide them with broad-based skills that they will put to use in any number of ways–providing that they think strategically and entrepreneurially about their futures. The implicit message is that they must take responsibility for those futures.

Of course, if you want to be, say, a civil engineer or a speech pathologist (no doubt important careers), then you’d better get into a very specific program, one in which a national professional association or credentialing body determines pretty much all of the courses one must take, the information one must cover and then retain from those classes (i.e., standardized professional exams), and the sequence of the curriculum. But despite their general freedom from such professional oversight, the Humanities, understood as I see them, demand far more of a student–that students step up, at a relatively early age, and take responsibility for shaping themselves and not simply rely on professional associations to tell them what they ought to be interested in and how to go about studying it. It can be intimidating, of course–awash in a sea of choices, with few criteria and reference points for deciding what to choose–but also incredibly empowering; and that’s what suggests to me that Humanities students, inventing themselves in the very act of going through a course catalogue, are the boldest and most inventive students in the contemporary, largely professionalized, University.

Whether this is what parents want to hear, I’m not sure, but I tend to think that, when they think it over, many are content with this answer, because it seems to me that their role, as parents, is to prepare their child to move from being an infant who is completely dependent on them to being independent, confident, and thus empowered adults who make their own way in a complex world. Trusting their decision to tackle an undergraduate Humanities degree, where that path is not necessarily pre-established for them by others, seems a pretty good place to start on that journey.

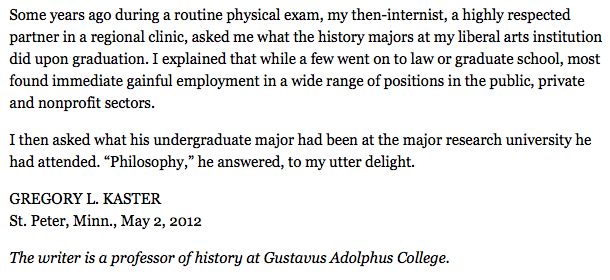

So with that in mind, one brief letter to the editor in reply to Bruni stood out for me:

Knowing that, over the past decade, our own Department has graduated students who went on to become medical doctors and lawyers, not to mention small business owners and public school teachers, I was inspired to do a little digging. I learned that Frank Bruni has a B.A. in English (thanks Wikipedia) and a Masters degree in Journalism (The New York Times’ blurb on Bruni lists his M.S. degree’s specialty but not his B.A.–a significant choice or merely an oversight?). What’s more, among his beats for the Times was that of restaurant critic and Rome bureau chief. He’s written books as well, one of which was on the Roman Catholic child sex abuse scandals. And now he has opinions on how the choice of an undergraduate major must be aligned directly with the career one eventually develops.

Knowing that, over the past decade, our own Department has graduated students who went on to become medical doctors and lawyers, not to mention small business owners and public school teachers, I was inspired to do a little digging. I learned that Frank Bruni has a B.A. in English (thanks Wikipedia) and a Masters degree in Journalism (The New York Times’ blurb on Bruni lists his M.S. degree’s specialty but not his B.A.–a significant choice or merely an oversight?). What’s more, among his beats for the Times was that of restaurant critic and Rome bureau chief. He’s written books as well, one of which was on the Roman Catholic child sex abuse scandals. And now he has opinions on how the choice of an undergraduate major must be aligned directly with the career one eventually develops.

Despite not becoming a high school English teacher or a Professor of Literature–the two career paths directly related to his B.A. training–things seem to have turned out okay for Frank Bruni, which makes his criticism of people with his own background, doing what he himself apparently did, just a little puzzling (though Merinda Simmons‘s recent post might start to explain it). No doubt he worked hard (after all, his blurbs are sure to tell us that he’s a member of Phi Beta Kappa and that he graduated second in his Journalism class, “with highest honors”). More than likely, he was as strategic as he could be and very entrepreneurial, making the most of the skills he had in a hectic marketplace where the unexpected happens all the time–after all, who thinks they’re going to become a New York Times restaurant critic? Not Frank Bruni, that’s for sure: “But his surprise appointment to this apparently enviable job–paid to eat in a city known for excellent restaurants–was to be, for deeply personal reasons, the greatest challenge of Bruni’s life.”

So I’m guessing that he’ll land on his feet if the print newspaper industry ever goes in the direction that many now predict (notice how many links to online newspaper articles I’ve posted here?) or if people no longer wish to pay to read opinions (after all, bloggers like me are full of opinions). Why? Because Frank Bruni–like the students at the University of South Florida who had a thing or two they wanted to tell their Governor who, like Bruni, singled out Anthropology as a less than useful major–is a nimble, independent-minded Humanities major who was trained to do more than just one thing.

As I see it, Frank Bruni is a real success story for the the Humanities. Someone ought to award him an honorary doctorate. With the highest honors.