As the AAR presents its newly drafted Religious Literacy Guidelines, Sierra Lawson (BA ’17, MA ’19) and Prof. Steven Ramey return to their research on the implications of classification to raise important questions about the politics and consequences of such a framing.

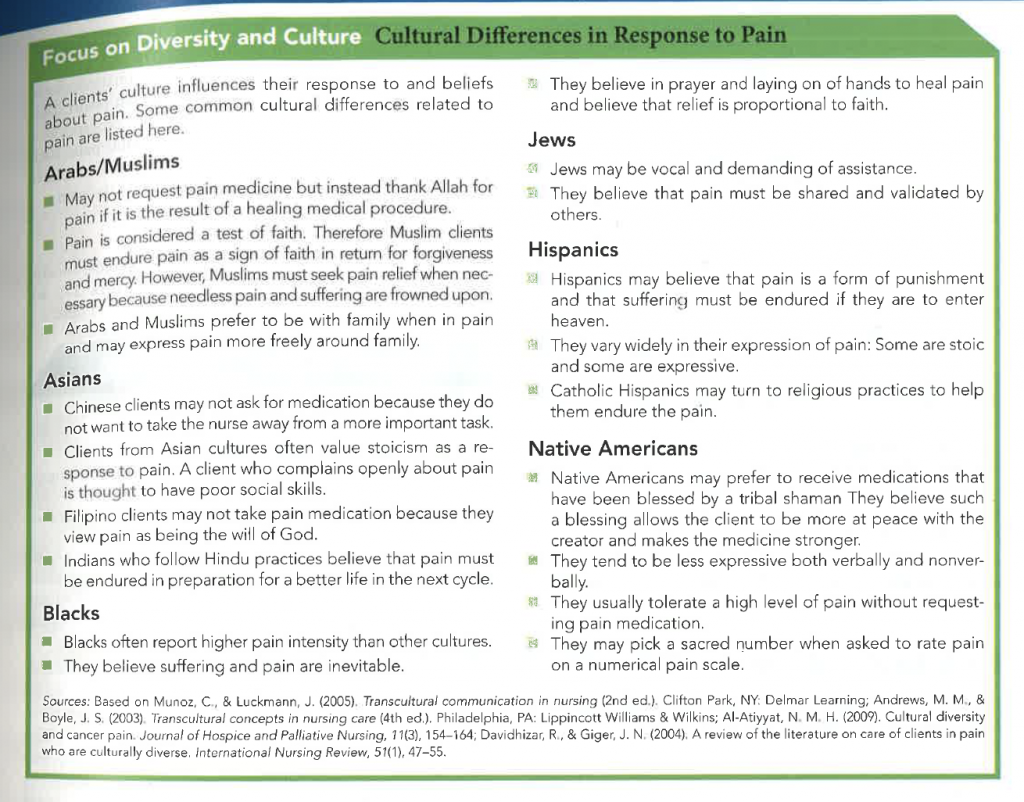

Religious literacy, which typically refers to knowledge about religions, differences between religions, and diversity within each religion, can reinforce problematic claims about social groups (as evident in the chart reproduced above). Useful knowledge can easily become harmful, especially when it tends towards selective generalizations and ignores the issue of who is doing the talking.

The AAR recently released “Religious Literacy Guidelines,” drawn out of a multi-year conversation and study. These guidelines encourage developing “credible knowledge about diverse religious traditions” and “recogniz[ing] the internal diversity within religious traditions,” among the five points of the guidelines. What these guidelines leave out is the process by which individuals participated in the production of this knowledge and delineation of diversity. While the fifth point of the guidelines argues that literacy should include the ability to “distinguish confessional or prescriptive statements made by religions from descriptive or analytical statements,” that statement in itself fails to acknowledge the agents behind these statements. Religions do not “say” anything; people who identify with a religion make statements. As Stephen Prothero, who has written about the need for religious literacy, asserts in the introduction to his new text on world religions, “Islam does not ‘say’ anything-that is the job of Muslims-so we should not begin a sentence with ‘Islam says,’” and then expands that point to other religions. Moreover, descriptive and analytical statements also come from someone, and research over the past several decades have shown the unquestioned assumptions that have often informed those descriptive and analytical statements. Ignoring the choices of the speakers cloaks those statements “made by religions” with the authority (whether the reader considers it to be positive or negative authority) of a particular religion and hides the influences (social, economic, political, theological, etc.) on that individual’s interpretation. Hiding these dynamics and generalizing an interpretation to an entire religion undermines the second point about diversity within any religion.

Asserting that students need to develop particular knowledge about diverse religions and diversity within religions without considering the production of that knowledge can discourage students from thinking critically about the information they encounter, both within and outside of the classroom. The guidelines themselves present as an example a site where uncritical religious literacy has created negative outcomes. The authors of the guidelines state, “Students training in healthcare careers need to learn how religious beliefs affect a person’s willingness to seek care or accept certain treatments.” As we wrote a year ago, teaching the effects of religion and ethnicity on responses to medical care can be hugely problematic.

Our research started with a recent controversy over a nursing textbook chart (pictured above) that generalized about the ways Hindus, Jews, Catholics, Muslims, African Americans, and others respond to pain. This work prompted us to analyze the production of the knowledge presented in the chart in an article published in Culture and Religion. From the review studies that the chart cited, we found references to a range of medical studies on pain. Some of the findings of those studies supported what the chart said, but they were often based on a limited sample. For example, a study of male veterans at a New York hospital, separated into different ethnic and religious/cultural groups, was the basis for the chart’s assertions about Jews, simply asserting that Jews are demanding—an assertion they generalize to all Jews by ignoring other data points in their sources that challenge such a claim.

Even worse, statements about African Americans not only generalized from narrower studies but also ignored contrary findings cited in the same review articles. And the contextualized nuances related to the cited studies suggest that the generalized behaviors in the chart could be a response to inadequate treatment in minority communities. By eliminating the context and nuance of studies focusing on African American communities, the chart’s statements reinforced a cycle of misinformation that results in the negative care that some in minority communities receive.

Therefore, any call to learn details about particular groups (which is central to this call to religious literacy) that does not directly train students to think critically about the construction of knowledge is lacking and potentially dangerous. Choosing which representations to include as generalized assertions about a group or subgroup involves the marginalization of many other voices. Gaining the critical literacy to think about who selects the interpretations that dominate presentations of religions, and what subgroups are ignored, is what education should emphasize. Anyone can look up details about a religion on Wikipedia, but educating current students in the academic study of religion is about considering who participates in re-presenting information about religions and how their choices have broader consequences. Thus, the supposed value of religious literacy for students ought to be reframed to emphasize critical analysis of the production of knowledge.

Sierra Lawson is a BA and MA graduate of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama who is now pursuing her Ph.D. in the study of religion at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Steven Ramey is a Professor in Religious Studies at the University of Alabama and Director of Asian Studies. His research focuses on contested contemporary identifications in India and around the world.