There’s an interesting article, from July 2006, making the rounds on social media. Published in the bilingual, peer-reviewed quarterly, Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, it’s entitled: “Editing a Normal Science Journal in Social Science.” It’s abstract reads as follows:

There’s an interesting article, from July 2006, making the rounds on social media. Published in the bilingual, peer-reviewed quarterly, Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, it’s entitled: “Editing a Normal Science Journal in Social Science.” It’s abstract reads as follows:

Using Thomas Kuhn‘s once well-known notion of normal science (a collective endeavor inasmuch as researchers share the same paradigm), the author, Linton Freeman, argues that work carried out in the sociological sub-field of social networks is more closely aligned with the natural than the social sciences (the latter being characterized by theoretical disagreement and methodological diversity far more than the former).

To make his case, Freeman compares three features across disciplines: acceptance rates to journals; number of citations in an article to previous work published in the same journal; and length of articles. His reasoning is that, given the consensus operating in so-called normal science, one would expect to see high acceptance rates, increased self-citation, and shorter articles. In the social sciences one would expect to see the opposite, of course.

Or, as he phrases it:

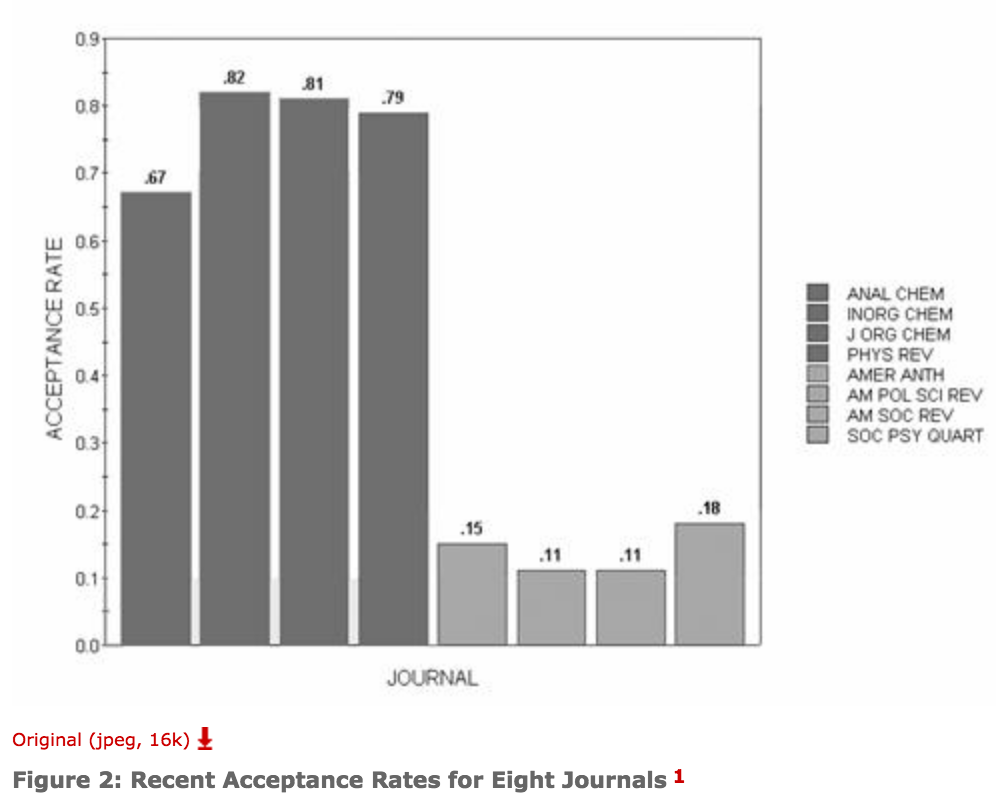

And this is indeed what he finds when he compares several natural science journals to social science journals. For example, consider the dramatically different acceptance rates:

While there may be other ways to account for his findings (e.g., since one table’s worth of data can represent months or year’s worth of work, a shorter article in the natural sciences does not necessarily signify agreement), it does accord with some of my own experiences in the academic study of religion; for inasmuch as one presupposes the field’s dominant narrative one has far greater freedoms in ones writing. To rephrase, if ones work questions any of the basic premises of the dominant school of thought (such as calling into question the world religions model so many still presuppose, or questioning the presumption that what we term religion is a secondary, empirical manifestation of a dynamic, inner quality called faith or experience), then it means considerable effort must go into arguing for just the basis of your research, something necessarily done before even getting on with the business of your work — and voila, a seemingly simple research topic turns into a lengthy exercise in persuasion.

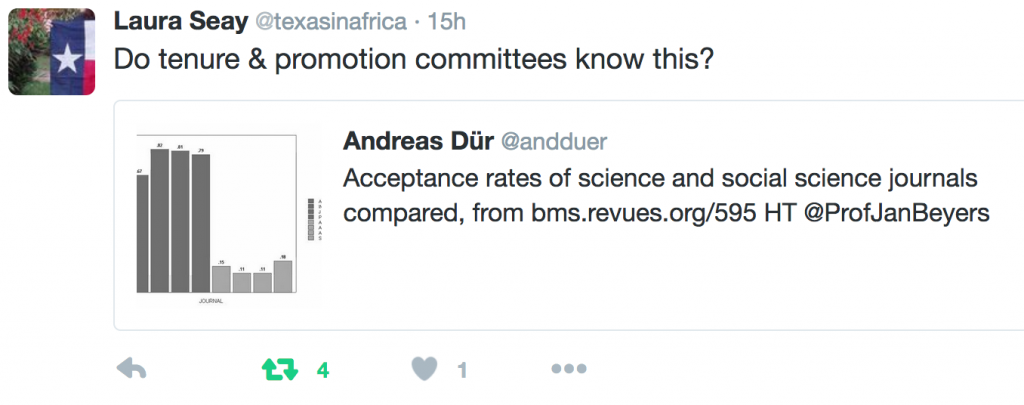

Most interesting to me, though, was the acceptance rate — something I first encountered in the following tweet:

While there may be various reasons for the differences in acceptance rates across disciplines (e.g., some journals might be trying to increase their “impact factor” by being seen as ultra-selective [though the presumed link is dubious] or there may be far more journals in the natural sciences [driven, perhaps, by the more direct relationship between research and capital] and thus their editors may have the luxury of more generous standards than their social science peers — for, at the end of the day, they must fill that issue’s pages, after all), it is worth mulling over — as Seay suggests in her tweet — the relationship between acceptance rates (along with, I’d add, the number of credible venues for publication), on the one hand, an, on the other, how we judging an individual professor’s research productivity, as we now phrase it.

While there may be various reasons for the differences in acceptance rates across disciplines (e.g., some journals might be trying to increase their “impact factor” by being seen as ultra-selective [though the presumed link is dubious] or there may be far more journals in the natural sciences [driven, perhaps, by the more direct relationship between research and capital] and thus their editors may have the luxury of more generous standards than their social science peers — for, at the end of the day, they must fill that issue’s pages, after all), it is worth mulling over — as Seay suggests in her tweet — the relationship between acceptance rates (along with, I’d add, the number of credible venues for publication), on the one hand, an, on the other, how we judging an individual professor’s research productivity, as we now phrase it.

For although this data is ten years old — and gathered somewhat unsystematically, i.e., consider footnote one:

— it does prompt one to be less ready to compare research accomplishments across disciplines. (Interested in some more recent data on psychology journal rejection rates? Compare that data to the rates [reported in 2010] in, say, Atmospheric Sciences journals [see Table 2 in that paper].)

Applied to our own field: in an organization reported to have nine thousand members, just how many people can credibly be expected to get a spot on the annual program, no matter how large it has grown, let alone a publication in the Academy’s main peer-review journal (a quarterly that annually publishes only thirty or so original and presumably peer-reviewed articles — not counting book reviews, review essays, solicited essays, responses, etc.)? While I don’t know JAAR‘s rejection rate, and despite my disagreement with some work I see in its pages, I would presume that it is rather high. And other than specialized journals in this or that sub-field, there’s really only a handful of broad journals that try to cover our entire field — making it a challenge, presumably, to find ones work published in any of them.

And so, while there are plenty of credible critiques of the current trend toward university administrations using such resources as Academic Analytics to compare faculty and determine their individual productivity, this article makes evident the need to compare like with like, as AA at least makes possible; if we must compare, then scholars of religion ought to be compared to other scholars of religion as opposed to judging us alongside, say, Physics or Chemistry profs — people who seems to have little trouble finding a home for their research and thereby reporting yet another article in their annual productivity reports.